By Lavelle Porter

1

Samuel Delany is wrong. Wrong. Wrong. Wrong. His latest novel Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders is absolutely the wrong kind of book for the current moment, an 804-page cinder block of a novel in a digital age where everything in literary culture militates toward shorter forms: one-hundred-page ebooks, or short Scribd documents, or Tweets. And the subject matter of Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders is all kinds of wrong for this political moment in the gay rights movement. The assimilationist liberals at GLAAD and HRC have struggled mightily to disentangle the gay rights movement from the seedier side of gay life, and have done their level best to reassure straight people that gays and lesbians are just normal folks who really do want to settle down with one partner, get married, have children, fight in the military, and go to church. But along comes Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders, precisely the kind of gay novel that mainstream gays would prefer the vicious homophobes at the American Family Association never found out about. It’s a relentlessly nasty book filled with detailed descriptions of some pretty raunchy sex acts involving the consumption of bodily fluids and waste, characters who get off on calling each other racial slurs, and scenes of incest, bestiality, underage sex, promiscuity, polyamory, and more. Television and the Internet are feeding us images of fashionable photogenic young urban homos coming out every other day. Gay couples are happily marrying all over our screens, beautiful A-list queers like Rachel Maddow and Anderson Cooper and Don Lemon now sit “out and proud” at their desks on mainstream news networks, gay couples are adopting children, gay athletes are coming out in sports, and gay soldiers are coming out in the military. But these three Delany books are chock full of all the wrong kind of queers: poor, uneducated, disabled, old, fat, ugly, and promiscuous.

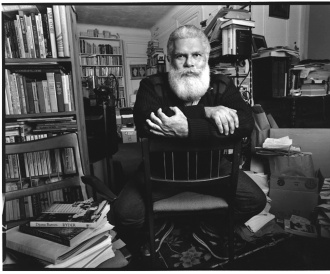

To be sure, Delany has been a staunch advocate of gay rights (as well as an anti-racist, pro-feminist writer). His early science fiction contained subtle expressions of homosexual desire, most notably in the short story “Aye, and Gomorrah” which won the 1967 Nebula Award for short story science fiction. He wrote one of the first pieces of fiction to address the HIV/AIDS epidemic with “The Tale of Plagues and Carnivals” in Flight from Nevèrÿon (1985), and he’s written extensively about the evolution of gay politics from the vantage point of someone who has lived as openly gay on both sides of the 1969 Stonewall Riots. If there is one thing that defines Delany’s writing on sexuality it is that he is thoroughly unwilling to acquiesce to “good gay” conventions. He goes on writing pornographic novels (and cheerfully owns the label of pornography) and talks openly about how he has had sex with over 50,000 people (see the 2007 documentary film The Polymath, directed by Fred Barney Taylor), and writes in detail about the medical details of his own sex life, such as in the eye-opening article “The Gamble” published in the 2005 issue of “Corpus“, a journal from APLA (AIDS Project Los Angeles). And altogether, Delany has put together one of the most impressive careers in American literary history. He has published over forty books across a range of genres, including science fiction, fantasy, literary fiction (what he calls “mundane” fiction), literary criticism, and graphic novels. Despite never having finished college himself (after graduating from The Bronx High School of Science in 1959 he attended City College of New York for less than a year), he has taught as a professor at University at Buffalo, the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, and currently at Temple University.

2

Several other very capable critics have already written eloquently about Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders, including Jo Walton at Tor.com, and Roger Bellin in The Los Angeles Review of Books, and Paul Di Filippo at Locus, and Steven Shaviro on his blog The Pinocchio Theory. But there is something in their analysis that strikes me as all too hip. We get it that Delany can take pornographic material and make it warm, fuzzy and fulfilling rather than violent, degrading or threatening, the way many intellectuals tend to talk about pornography. But there’s some seriously challenging material in this novel. Of all the reviews, only Jo Walton’s piece came closest to really addressing the ethical challenges that this novel presents, and her review spawned a particularly thoughtful conversation in the comments section about the way children’s sexuality is represented in the novel.

3

So much of Delany’s writing is about cities, the type of people who live in them, the way they function, and the sexual underground that one can find in them. He’s written extensively about his hometown of New York City, including 1999’s Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, one of the best books written about the social, political, and economic factors at work in the current gentrification push in New York. In this novel, however, Delany ventures away from the city and into the rural South.

When we first meet Eric Jeffers he’s (literally) sixteen-going-on-seventeen, living with his stepfather in Atlanta and preparing to move to the small town of Diamond Harbor in coastal Georgia to live with his mother Barbara. His stepfather Mike is black, a laborer who did a short stint in prison when Eric was younger. Mike met Eric’s mother Barb when she was an exotic dancer in Maryland. She has since left the nightlife and now works as a waitress at a diner in Diamond Harbor.

The town where Barb lives also happens to be near a community affectionately called “The Dump,” a community founded and financed by a black gay millionaire named Robert Kyle III who grew up in Diamond Harbor. Eric doesn’t realize that when he moves there he is about to stumble onto a strange and wonderful paradise that will become his home for the next sixty years.

Shortly after moving to Diamond Harbor Eric meets Morgan Haskell, who never goes by the name Morgan, but by his nickname “Shit.” Shit and his dad Dynamite work as the community’s garbage men, paid by the Kyle Foundation, and they soon take on Eric as an employee and lover.

After setting up these conditions, the rest of the novel plays out simply, concerning itself with the inexorable march of time. Eric adjusts to his new life in Diamond Harbor, adjusts to his new job as a garbage man, and finds the job meaningful and fulfilling despite the fact that Barb wishes he would go to school and work at something more lucrative. Barb’s new boyfriend, Ron, castigates Eric for not wanting to move up into a better job. Ron is a particularly interesting character: black, conservative, a striver, working as a computer technician, and one who loves to have pretensions of upward mobility. I couldn’t help being reminded of Wendell Pierce’s trash-talking black Republican character in Spike Lee’s Get on the Bus. Brother Ron is cut from the same cloth. And their interactions do stimulate Eric’s ideological perspective, helping him to shore up his own philosophies on life. Ron keeps insisting to him that he should want to work in a place where he can wear a suit and tie and be around nice people. Eric realizes quickly, however, that he already lives around nice people, and that the “nice people” Ron wants him to be around are the very people who tormented him in high school and who look down on the man he is falling in love with—an illiterate garbage man who lives with his father, and is, frankly, more than a bit of a pervert.

The sexual content of the novel is unrelenting. I suppose I understand what Delany is up to here. This is a novel that is precisely about having sex, about all the ways that a particularly precocious young white gay man with a thing for black guys, and a plethora of kinky desires, can explore the fullest possibilities of his sex life. Most novels are about not having sex, about the containment and regulation of sexual desire internally and externally. That said, it gets tedious. Don’t just take my word for it; read the other reviewers. There’s even more piss-drinking, snot-eating and shit-eating than in Delany’s notoriously raunchy pornographic novel The Mad Man, which is saying a lot. But whereas in that book the activity veered toward the excessive, and playfully stretched the boundaries of the reader’s tolerance, this one just goes over the line. It’s too much, and it begins to obscure what is really a wonderful story that builds and builds in the second half of the novel. I found myself starting to skip and skim the sexual passages to get back to the narrative of the characters’ lives. Having read quite a bit of Delany I want to trust that there is some intent in this, some way that he is manipulating the reader into thinking about language in creative ways. Mostly, though, it was a distraction.

The second half of the novel pushes forward into the twenty-first century, and Delany’s particular gift for speculative fiction starts to take over. His description of the 2030s especially resonated with me. He portrays them as a wonder decade, much like the 1960s that defined his own generation, or the 1920s that defined that of his parent’s. One doesn’t think of them as “wonder decades” as they are happening, only in retrospect. Part of what happens in the 2030s is that humanity finally has its day of reckoning with nuclear weapons as atomic bombs explode in California and Brazil, and the world finds a renewed sense of community in the aftermath of these unspeakable catastrophes. New technologies emerge as well, including wearable nanotech that transforms the way people buy and wear clothes. All the while, the citizens of Diamond Harbor lead some very low-tech lives, at times unbelievably low-tech. Eric shuns the cell phone, and sticks to reading his physical copy of Spinoza’s Ethics even though other forms of media are available. “Shit” is illiterate and mostly uninterested in television, reading or computers. But their lives seem implausibly free of the kind of network technology that is already dominating our experiences now, even in the rural South. The narrative works all the same, though I still find it hard to believe that living on the Georgia coast will make it possible to escape the Network entirely (particularly after having just spent a week in Mississippi and Alabama where smartphones and tablets abound even among the poor and semi-literate populations).

As the novel moves on, deaths start to mount, age starts to take its toll on Shit and Eric, and the ending of the novel is heartbreaking and beautiful as we watch their lives wind down to the finish. And in the end, for all its flaws, this is a novel that no other writer could pull off, stamped with Delany’s particular genius and sensibility.

4

In a journal article titled “Clean: Death and Desire in Samuel R. Delany’s Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand” published in American Literature in 2012, Graduate Center Professor Robert Reid-Pharr delivers a rather clever observation about Delany’s work:

I would note, however, that this is the point at which Delany’s novel becomes most difficult to read. For though on Velm, in Morgre, and at Dyethshome one finds the author celebrating all of the shibboleths of our own self-satisfied liberalism – respect for diversity, freedom of movement and association, humor, generosity, erudition, and a certain easy gentility – Delany does not seem satisfied to leave well enough alone. He insists, that is, on repeatedly sticking those fat and unwashed fingers of his into an altogether well-made pie. He will not allow us to forget, even and especially in the beautiful halls and gardens of Marq’s home, the fact that all of these effects, all of these lovely sentences, are underwritten by brutality and violence that are, for lack of a better description, world-shattering.

And that’s just it. What strikes me about the sexual politics involved in Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders is that Delany just won’t leave well enough alone, especially when it comes to the self-satisfied political gains of the LGBT movement. One of the unique things about Delany’s pornographic novel Hogg is that it contained all the things that conservatives at the time (this was during the pre-Stonewall years) were saying about pornography. He took their fantasies of violence and murder and played them out in a story about a rapist-for-hire, and the twelve-year-old boy who hangs out with him and becomes his protégée. In a similar fashion, I think in TVNS, Delany dares to imagine the very slippery slope that the conservatives have warned us about. Played out in a utopian community on the Georgia Coast, Delany cheerfully tumbles down that slippery slope. No, there is no one who gets married to a goat, but there is some frank discussion about and acts of bestiality, there’s a polyamorous household raising children together, there’s Whiteboy and Black Bull, a sadomasochistic couple who live across the road from Shit and Eric and Dynamite, there’s public sex, even welcomed and encouraged in the city’s infrastructure.

5

A sign of the times: As I’m writing this review, Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders, published in April 2012 by Magnus Books, is already out of print. Recently a fan on Delany’s Facebook page alerted him to the fact that print copies of the novel are being listed by second hand sellers on Amazon for hundreds of dollars. Delany replied:

It’s not necessarily a good thing…In this case, it’s because the publisher can’t afford to go back to press and print more paper copies; this means for the last six months, at every reading I have done, in Boston, in Washington D.C., in Boulder, in Philadelphia, in Atlanta, in Seattle, in L. A., in New York, no books were available to sell to the people who came, nor are any available in bookstores in those cities. And neither the writer nor publisher gets any money at all from those artificially inflated prices you see on Amazon, once a book becomes generally available. THROUGH THE VALLEY OF THE NEST OF SPIDERS is still available on Nook and Kindle (at $9.99), from which I get a much smaller royalty than I would from a standard priced sale of a paper volume, but that’s all.

So that’s where we are in the world of literature these days.

The good news is some of Delany’s criticism is coming back into print thanks to the good people at Wesleyan University Press. Phallos, originally published in 2004 by the small press Bamberger Books has been reissued in an “Enhanced and Revised” edition that includes critical essays by Robert Reid-Pharr, Steven Shaviro, Ken James, and Darieck Scott. Likewise The Jewel-Hinged Jaw: Notes on the Language of Science Fiction, and Starboard Wine: More Notes on the Language of Science Fiction are both back in print in handsome paperback editions, also from Wesleyan.

6

Technology and change play a significant role in these Delany books, as they always have done in his work. Part of the novel Phallos is presented as a print version of a website that features a long excerpt from a mysterious anonymously authored pornographic novel, also called Phallos. The story follows the quest of young black intellectual Adrian Rome to figure out the origins of the book. The playful reflexivity of the book-on-a-website-in-a-book form is cleverly represented by the cover of the new Wesleyan edition of the novel, which features a photo of the previous edition of Phallos. The graphic novel Bread and Wine is another Delany reissue, this one put out by Fantagraphic Books. It is the story of Chip, his partner Dennis Ricketts, and their relationship which started on the Upper West Side in the 1980s and is still going strong twenty-five years later.

In a recent interview with Paul D. Miller, a.k.a. DJ Spooky, Delany warns against over-determined autobiographical readings of his work, particularly when the critics get his autobiography completely wrong. In that interview Delany describes a reviewer who referred to him as a poet (Delany has never published poetry), and made other factual errors. That said, it is obvious that there are pretty specific similarities between some of the biographical details of Delany’s life and some of the characters in his work. Reading Bread and Wine one can see how there’s more than a little bit of Chip and Dennis in the relationship between Shit and Eric in TVNS. Delany’s academic novel The Mad Man also drew on some of the same source material. In that novel, the young black academic philosopher John Marr meets a hefty homeless man named Leaky and starts a relationship with him, with Leaky eventually moving into John’s apartment.

Bread and Wine is beautifully illustrated by the artist Mia Wolff. Her renderings of nocturnal New York turn the city into a magical enchanted landscape where these characters find each other on the streets of the Upper West Side, sniff each other out for a while (figuratively and literally) and decide that they get along well together. The story disrupts some of the assumptions of inequality in the relationship between a homeless white drifter, and a black novelist and professor. Dennis was just as apprehensive about the relationship with Chip as Chip was about taking in a homeless man. All throughout, their story is framed by excerpts from German poet Frederich Holderlin’s poem “Bread and Wine.” Removing the book jacket of this hardcover edition reveals some amazing watercolor portraits of Chip and Dennis on the covers, and the back of the book features a new interview with Chip, Dennis and Mia explaining more about the origins and composition of the book.

7

Despite the fact that Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders is a difficult reading experience, and maybe not among Delany’s best fiction, the book also manages to encapsulate everything that Delany is all about. It comes down on the side of kindness over meanness, empathy over indifference, compassion over cruelty. And there’s nothing naïve or shallow about it. The characters find ways to be good to each other despite the trials and horrors that befall them and that befall the communities to which they belong.

That’s what all that Spinoza stuff in the novel is all about. To the extent that one wants to believe in an ethical version of a God, then one must think of that God not as a being separate from creation, but a being whose essence permeates and connects all things. That is hardly an original idea, nor is it at all presented as an original idea in the novel. Eric ruminates over the meaning of God as he reads and re-reads his Spinoza book, and the meanings that he draws from the book resonate with Buddhism, Unitarianism, or other spiritual systems.

The difficulty is in seeing the continuities between all things: truly seeing excrement, trash and waste products, and learning to “love” them radically. The novel would be a much less provocative exercise if it were obvious that all this piss drinking and snot eating was just a metaphor. It is the materiality of Delany’s writing that makes the reader imagine it as literal. Both literal and metaphorical. To put it in Christian terms, I think of Delany as ol’ doubtin’ Thomas, who just won’t accept the story that the man standing in front of him had risen from the dead, and just has to reach out and stick his hand in the bloody wound to see if it’s real

8

Bread and wine, bread and wine. It is hard not to see some religious and spiritual themes at work here, even though Delany is an avowed atheist. In TVNS Eric’s readings of Spinoza’s Ethics, and his conversations with the ex-seminarian turned drag queen named Mama Grace who gave him the book, help him to make sense of his desire to live a good life and be a good person, and shape his perception of his place in time, space and eternity.

I recently caught up to Tracy K. Smith’s Pulitzer Prize winning poetry collection Life on Mars. Among the poems in that wonderful book is one called “It & Co.” I came across that poem while re-reading some passages from TVNS and it beautifully resonated with the spirituality that Eric develops throughout his days in The Dump as he reads and re-reads Spinoza. It also resonated with this big, difficult 800 page novel that I was working my way through, once again:

We are part of it. Not guests.

Is It us, or what contains us?

How can It be anything but an idea,

Something teetering on the spine

Of the number i? It is elegant

But coy. It avoids the blunt ends

Of our fingers as we point. We

Have gone looking for It everywhere:

In Bibles and bandwidth, blooming

Like a wound from the ocean floor.

Still, It resists the matter of false v. real.

Unconvinced by our zeal, It is un-

Appeasable. It is like some novels:

Vast and unreadable.

Pingback: The Strange Career of Samuel R. Delany | BLACK MAN IN THE COSMOS

Can I just say that after discovering TVSN via recommendation of cutting-edge contemporary SF novels that this review was what I was looking for? I was almost instantly stricken some few hundred pages in by how excessive the entire thing was and went meandering around the internet looking for anyone who shared my thoughts. Instead, I ended up reading article after article of what I call “progressive progressives”—those people who are politically and ideologically progressive simply for the sake of being so—who were citing Delany’s absurd, almost spiteful (to the Right) porn in this book as trailblazing, and from there, somehow ended up down the rabbit hole of pedophilia and pedophilia apologism in SF (Delany has made pro-NAMBLA [for the unaware, a pro-pedophile organization] comments.) That I feel was another conversation apart from the main topic of TVSN.

And today, I stumbled upon the article. I echo a lot of the same sentiments you shared some five years later. So, thank you for this. I feel some sort of closure about my confusion over the overall un-critical, gushing reaction this book received. It could’ve done with some editing and a third party to ask Delany, “And outside of fueling your fetishes under the veil of speculative future fiction, why are you writing all of this again?”

I respect your opinion and admire the clear passion that you display in this comment. As a gay man, I understand where you’re coming from, however I have to disagree fundamentally with your claim that “Delany is wrong.” I actually really admire the graphic gay pornography that he displays in his novels, and I think that it is tremendously important. And I also see no shame in saying proudly how many people you’ve had sex with, and just being all around transparent about that. Perhaps for some people it can be off putting, but I admire and look up to his transparency. I get very frustrated with the idea that we cannot or should not be graphically displaying gay sex. I believe that graphically and explicitly portraying gay sex in literature, and all forms of fiction/art, is precisely what we should do to advance the public acceptance of being gay. At the current moment in time, there will never be a blockbuster Fifty Shades of Grey with gay main characters that will be adapted to the big screen. If the public only accepts us on the grounds that we aren’t allowed to talk about or reference our sexual exploits as freely as some of our straight counterparts, then that is an inherently problematic type of acceptance in my opinion. That’s one of the reasons why I think that Delany’s work, particularly his pornographic work, is more important than ever for LGBT rights.