Jenn Polish

We often write and talk over beers and coffee about watching our students grow over the course of the term. As writers, as students. As people.

We often write and talk over beers and coffee about watching our students grow over the course of the term. As writers, as students. As people.

But there isn’t a one-way observation glass between us and our students, even if we sometimes think of our classrooms that way. Our students watch us too. They watch us grow throughout the course of the term. And this term my students have watched a lot happen for me.

Makeup (not a lot, but enough to be noticed) and form-fitting clothes in the beginning of term—complete with long, curly hair, sometimes down, sometimes kept up somewhat clumsily in a pen-made bun—and a femmey style of presentation marked my first few classes. And then my clothes started shifting: looser pants, collared shirts. And then my voice started dropping. And then I came back from a weekend in Providence with my hair chopped off, a boy haircut so dramatic that my mentor at LaGuardia Community College, who was observing me that Monday morning—I have the pleasure of knowing him quite well—backed out of the classroom to confirm the room number because he did not immediately recognize the person teaching. A boy haircut so drastic—so, well, boyish, that my fiancee insists I’m the long-lost sixth member of ‘Nsync. (She says it with a smile, but I never quite know whether to be complemented or teased. Probably both.) And then I started binding. And then I told them.

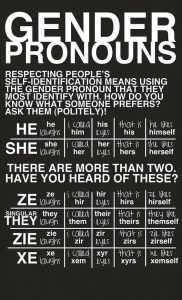

After spring break, I told my students that I’m transitioning into using they and them pronouns, and that when they’re talking to their friends about their English class, the proper way to do so is, “aw man, I hate my English class, my professor gives me so much work, they’re so annoying, instead of ‘she’s’ so annoying.’”

“My students? They nodded, and they laughed good naturedly at the self-deprecation.

And that was that.”

I don’t know their thoughts on the subject of my nonbinary transition and the qualms they might have about their professor coming out smack in the middle of the term as being on the trans spectrum. But I do know that I now feel more uncomfortable talking about queerness in class.

I know that I feel more uncomfortable pointing out textual references about one of the characters in the play we’re reading being gay; I know I’m more nervous about asking for my students’ preferred gender pronouns on their index cards at the beginning of next term than I was at the beginning of this term. Because next term, on the first day, I’ll be telling them my own gender pronouns, and they (no pun intended) won’t be the expected ones.

And that makes it feel harder, for me, to create a trans-affirmative classroom. Because identity impacts pedagogy, and being a white professor with all my white privilege makes my white students challenge me less when we slam white supremacy in the classroom. Similarly, being cis (or at least, cis-passing) makes it feel easier and safer to affirm my trans and GNC (gender non-conforming) students with policies, practices, and content (aka, pedagogy).

“Welp, there goes my cis privilege.”

And that’s okay. I think. I think it’s okay because it’s me, and it’s real (though cissexist logic, combined with my own borderline personality dis/order, which makes me question my own realness on a second-by-second basis, also makes me question the reality of my genderqueerness daily). And it’s okay because it feels like what I’ve needed; what I’ve been, my whole life, sans the vocabulary to articulate myself. To compose myself.

“So. To the title. Pronouns, privilege, and pedagogy.”

Pedagogically, it’s always been my practice to try to ensure that each lesson plan, each assignment design, each piece of assessment criteria, is inclusive of actively-solicited student feedback; that it affirms and welcomes as many learning styles as it can.

And my pronouns shouldn’t affect that, I suppose. Women professors get lower ratings than men do from students, so I guess pronouns already actively impact my teaching anyway. Now, just… differently.

I’m not sure how yet. But I am sure that teaching while binding, teaching while trying to keep my pen in my hair like I used to and having it fall out because there’s no longer enough hair to keep it in place, is an intimate experience. Explicitly intimate.

Because it’s intimate when I chuckle, looking for my pen, and say, “hmm, I have to get used to it not staying [behind my ear] anymore”, and my students chuckle along with me. And it’s intimate when my students blink and cock their heads and maybe smile a little bit, but say nothing, when I walk in with a newsboy cap and a boy haircut, breasts bound tight to my chest and a henley that never fit me right before that trip to Babeland changed my life (and my wardrobe).

Because it’s intimate when I chuckle, looking for my pen, and say, “hmm, I have to get used to it not staying [behind my ear] anymore”, and my students chuckle along with me. And it’s intimate when my students blink and cock their heads and maybe smile a little bit, but say nothing, when I walk in with a newsboy cap and a boy haircut, breasts bound tight to my chest and a henley that never fit me right before that trip to Babeland changed my life (and my wardrobe).

And I suppose what I’m asserting, pedagogically, is what I study in my academic work: an openness, a welcoming, an embrace, of that intimacy, instead of pretending that it wasn’t always, already, there.

Emotions in the classroom—fear, risk, exposure, reward, relief, excitement—are what we invite from our students each time we ask them to raise their hands and answer a question, each time we ask them to submit assignments to us by a certain date, each time we set them into group work and hope it doesn’t spiral any students into a panic attack (as it often does to me). But we’re trained not to think of it that way; we’re trained to be used to it, and so are our students.

But maybe these emotions shouldn’t be so normalized that they’re invisible: maybe it would be helpful to bring them to the fore, to acknowledge them, to integrate an understanding of them into our pedagogies, into our assignment designs, into our assessment practices. Maybe coming out as genderqueer— not just sexually— is as important to the development of my pedagogy as researching and writing academically about emotions in the classroom are.

I’ve been coming out as sexually queer for over a decade, so much so that I don’t think about it anymore. But genderqueer? It forces my body back into the classroom in a way that white privilege, cis privilege, had previously allowed it to be invisible (even when I didn’t want it to be).

Pedagogically, my body has become what I encourage my students to write towards: it’s okay if you don’t have a neat answer, a neat thesis, a cookie-cutter argument. It’s okay if you submit an incomplete draft, because no draft is ever complete. It’s okay if your project is not structured the way you were taught it should be structured; form reflects content, form shapes content, content seizes back on form and gives it a different flavor. (All this, of course, involves contract grading — determining together with your students what they need, what they expect, from their time put into your class — because without said contracts, there is no structure by which to give students what, ultimately, they need to keep their financial aid and such: grades.)

So what has coming out as nonbinary taught me about my pedagogy? I’m still figuring it out: but I think it has something to do with the constancy of growth, the power of vulnerability in the classroom, the risks we daily expect our students to take, and our (un)willingness to take similar risks ourselves. I’m still figuring it out: and, pedagogically, that’s a decent place to be.