Angelica Pickens and Gordon Barnes

In the 2016 film Elle, a psychological thriller delving into issues of rape and rape fantasy, Isabelle Huppert portrays an upper-middle class French woman, Michèle, who is violently raped by an initially masked assailant. She opts not to report the assault to any authorities and instead engages in a drawn-out, lustful game of (seemingly consensual) sex and violent encounters with her attacker, who is later revealed to be her neighbor Patrick. Central to the movie’s plot is the inability, or at the very least, the uneasiness with which the audience tries to determine if the post-rape encounters are in fact consensual. In every encounter, it is debatable whether Huppert’s character is being raped or if she is engaging in a particularly dangerous form of rape fantasy. This ambiguity is exacerbated given the fact that Huppert’s character never verbally consents to any of the sexual or physical acts which take place between her and her attacker. What this film brings into relief with regards to gender relations and sexual violence, amongst other things, is the problem of rape fantasy. At what point does the fantasy of rape, even if all participants are eager and willing, constitute a socio-political problem? Or does it at all, if indeed all participants have consented?

What follows originated as a debate between the two authors over the ethical implications of rape fantasy. Pickens, a neuroscientist, and Barnes, a historian, claim no authority over these topics, and intend this article to delve into the ethical and social issues around rape fantasy. Due to the authors’ contrasting views on some issues, portions of the article will refute one another.

Rape as a Manifestation of Female Oppression

Before we delve into the ethical intricacies of rape fantasies, it is essential to begin with a brief description of the origin of rape itself. The occurrence of rape as a socio-sexual phenomenon is inextricable from the hierarchy of the sexes and consequently from gendered social divisions. Although the act of rape has existed since before humans evolved as a species, rape as a manifestation of the oppression of women and biological females has only come about in a classed society. Friedrich Engels describes a married woman living in the era of capitalism as “the slave of [her husband’s] lust and a mere instrument for the production of children.” The ratification of the marriage certificate by the bourgeois state is the legitimization of the deed for a slave over whom the benevolent owner has dominion for life. In this way, the institution of the nuclear family becomes the societally ordained deterioration of women’s existence into “domestic slavery,” as Lenin was wont to say. The dominion of the head of household over his dependents knows no limits – in the not too distant past, and still today in many places, the husband is able to rape his wife at will and face no consequences. In the United States, the “land of the free,” marital rape was federally outlawed only in 1993, although domestic abuse is still widespread today.

In addition to being subject to sexual violence in marital relationships, women are also raped by boyfriends, family members, friends, and acquaintances. Rape by strangers occurs but at disproportionately lower rates than rape perpetrated by someone who is known to the victim. Rape occurs at parties and family gatherings, on dates, and while spending time with those the victims believe they can trust to respect their autonomy over their own bodies. Feminists today sum up the occurrence of and societal tolerance for rape with the term “rape culture.” Rape culture is enabled by the dehumanization of women and the devaluation of the sovereignty of females over their bodies, by the lack of support for rape survivors who choose to report sexual crimes, and by the widespread rhetoric that inculpates the victims for the crimes. Rape apologists often condone or justify rape by attributing its reasons to the victim wearing revealing clothing, being out too late, or choosing to spend time with male individuals outside of family members and committed partners. In this way, rape is used as a tool for controlling women’s behavior, thus subjugating and relegating them to second-class citizenship.

These sociological and political motivations for rape explain why men constitute the majority of rapists and women the majority of victims. Rape of men by women, while no less traumatic and repugnant than that of women by men, does not stem from the same gendered power dynamic. However, it is still the infliction of power upon the victim by the attacker (or attackers). The imposition of one’s power upon another individual is posited as one of the main purposes of rape.

Though rape is a deeply disturbing socio-economic phenomenon and a symptom of and tool for the oppression of women, rape fantasies amongst people of various genders are quite common. For an individual to have fantasies about this horrifying thing could be construed as intrinsically problematic. What we endeavor to interrogate over the course of this article is at what point the fantasy of rape becomes problematic, if at all. The issue of consent, and the ostensible desire for feigned non-consent inherent to the fantasy, is at the core of our exchange, along with attendant issues of power relations and violence. It is imperative that the reader understand that rape fantasy does not include all violent, atypical, or “kinky” sexual propensities – it is primarily characterized by the desire for a feigned lack of consent. Willingness to participate in violent or otherwise constrictive power relations is not the same as the desire to participate in a rape fantasy. The latter only comes into being once the issue of consent (feigned by at least one participant in the case of rape fantasy) becomes central to the sexual act.

The Questions of Consent

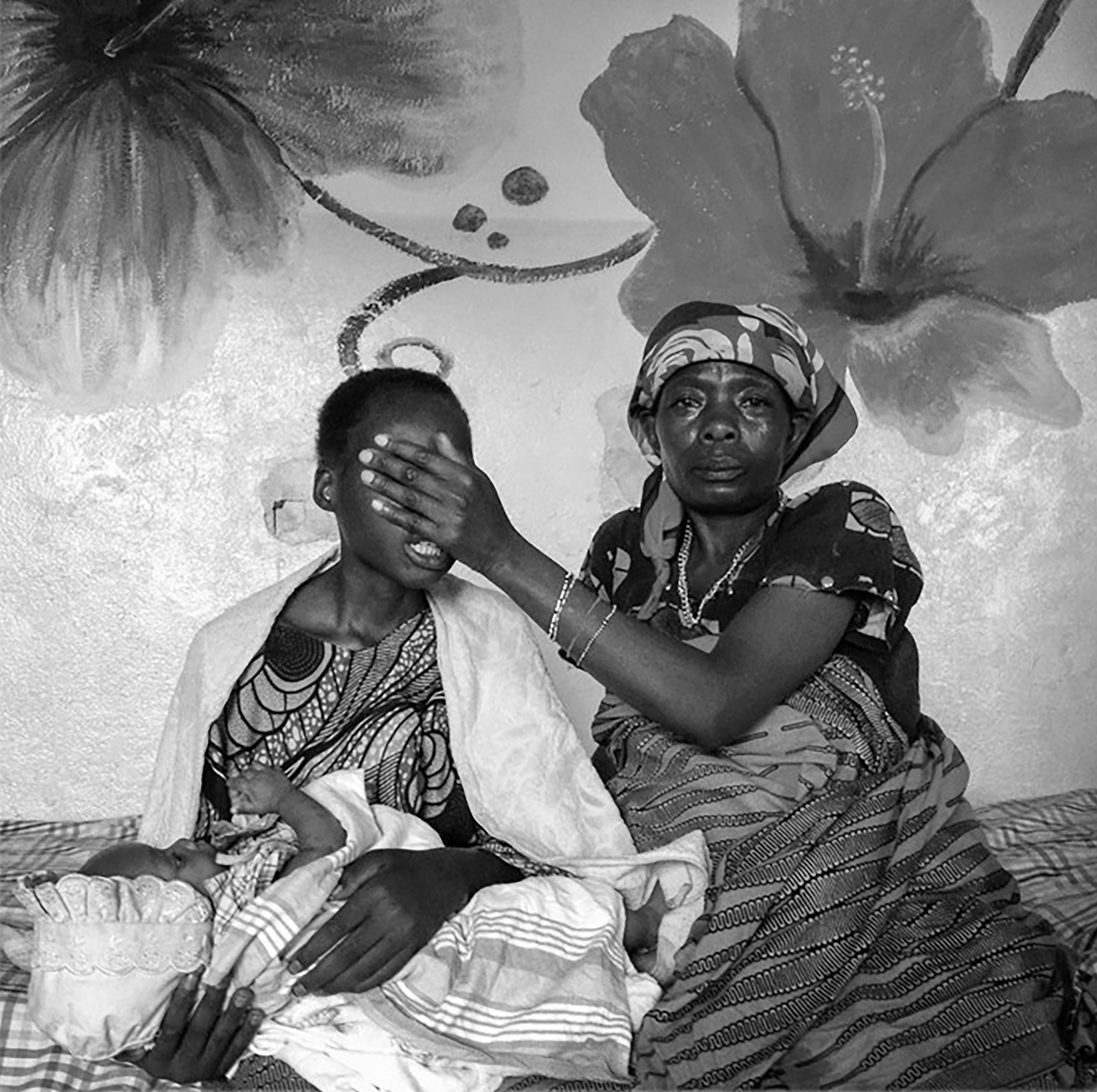

CONGO. Goma. August 9, 2012. A 16-year old girl from a village near the mining town of Numbi was raped by three Hutu militia fighters, one of whom impregnated her and gave her HIV. She did not know she had HIV at the time these images were made. She was at a HEAL AFRICA clinic in Goma with her child and her mother, who is covering her face in some of these images. Control over the mines, and the income they provide, has fueled conflicts in the area for decades, including violence against women.

As is seemingly evident in the film Elle, consent during sexual activity can be opaque. Of course, the recent clarion calls for affirmative consent from feminist and other activist groups combating so-called rape culture is generally the best way to go about engaging in sexual activities. With rape fantasy, however, feigned non-consent is not only desirous, it is necessary and integral to the sexual act. Therefore, at times, affirmative consent can serve to inhibit and stifle the fantasy. Certainly, partners can agree upon the parameters of their sexual encounter beforehand, but at the time that intercourse begins, it is perhaps unlikely that a person with a genuine rape fantasy—that is consensual sex played out as rape—will verbally ask to be “raped,” or to commit “rape.” Some may argue that this is precisely what safe words are for, but be that as it may, at the moment when copulation begins consent cannot be given in an affirmative manner, lest the rape fantasy devolve into sexual power play or consensual violence devoid of the feigned non-consent. So, can rape fantasy be consensual? Yes, but not in the style in which many advocates of affirmative consent would advance. This doesn’t inherently make rape fantasy a problematic form of sexual interaction, though it does blur the lines around what can be acceptable as the fantasy necessitates consent to masquerade as non-consent.

One cannot, of course, consent to being raped. But one can consent to pretending to rape or be raped. The ethical quandary this causes in relation to affirmative consent results in a grey area at the very moment intercourse commences. And while consent can be given in other ways, via body language for example, without both partners clearly assenting to the given activity, the line separating rape fantasy from rape has the potential to become quite tenuous.

Multiple definitions of consent differ on certain basic qualifications for what counts as appropriate consent. First, there is the question of what sexual acts can be consented to before and during a sexual experience. It is essential that all participants possess all the available and necessary information about possible experiences that could occur during the sexual encounter. It can be argued that only after mutual understanding of potential risks can participants fully consent to the encounter. Any activity is held to be acceptable as long as all participants are fully informed and able to consent without any sort of pressure to give consent. This excludes activities involving animals, children, and people who are otherwise incapacitated or coerced into participating. The main characters in Elle would be subscribing to this model of consent if they first took part in a conversation and mutually agreed upon the possibilities of the sexual liaisons. However, the viewer simply does not have sufficient information to ascertain whether the participants ever had a conversation like this, or whether the sexual relationship in which they are engaged emerged “organically.” That is, it is possible that the initial “rape” scene is indeed depicting an actual rape, and that subsequent “rape” scenes are more or less consensual after Michèle, the “victim” of the rape, somehow realized her enjoyment for being raped.

Some proponents of affirmative consent would say that the subsequent “rapes” depicted actual rape because Michèle did not verbally consent to them. Affirmative consent is of course a valid method for determining whether a sexual encounter is acceptable – if a participant does not want some sexual act to occur, that sexual act should not occur. However, this idea is taken to a utopic extreme when consent is required to be expressed verbally at all points in time. This misrepresents the idea of consent which is almost never purely “yes” or “no” but is more of a continuum of ongoing communication.

Further, verbal communication is not always necessary to affirm consent. A participant can affirm consent or indicate lack of consent through means other than a verbal “yes” or “no.” Try as they might, sexual partners will not always be able to negotiate a sexual situation as entirely equal partners. For example, gendered power dynamics are an almost unavoidable factor in heterosexual sex that must be taken into account. Women often feel pressured by men—even if those men do not mean to apply pressure—to engage in sexual acts. Similarly, many other factors influence participants’ decisions in an evolving sexual situation. Thus, even a simple “yes” is not always a true indicator of someone’s actual desire to take part in a sexual encounter.

There will always be grey areas of consent in any sexual situation, and it is futile to attempt to sort every situation into discrete black and white areas of consent and non-consent. This is reflected in several scenes in Elle – in all scenes but one, consent is not explicitly, verbally given, which could be vexing for viewers who are trying to ascertain whether the protagonists are engaging in rape fantasies or actual rape.

Contrastingly, during a violent scene in Patrick’s basement, Michèle tells Patrick, her would-be “rapist,” to hit her in the face. This ruins the moment for him, and he leaves the room. This raises questions about the nature of rape fantasies. To have a “true” rape fantasy, one must desire the complete lack of consent as reflected in actual rape. However, it is impossible to act out such a fantasy, as consent is essential to any sexual relationship. Thus, acting out a rape fantasy for most people does not necessitate a perfect simulation of real rape. Many or most individuals understand this distinction, and thus engage in rape fantasies while emphasizing the need for continuous consent. They do not see affirmation of consent as an obstacle to sexual gratification, they see it as an essential part of sexual activity. Some individuals hint at an actual lack of consent, obscuring and testing the border between a rape fantasy and actual rape. This seems to be where Michèle stands on the issue of consent; she does not explicitly consent to the “rapes,” but neither does she clearly convey a lack of consent. In contrast, individuals like Patrick who need absolute lack of consent (and in fact, complete resistance to sexual contact) do not have rape fantasies; they have the desire to commit genuine rape.

Rape: Fantasy and Desire

Central to the issue of rape fantasy is the question of desire. Rape in its actual form is never desired by the victim, but in the world of fantasy, both the “rapist” and “victim” are willing participants in the sexual experience. The majority of rapes and sexual assaults occur with the man as the former and a woman as the latter, whereas rape fantasies tend to be split, being held by close to fifty percent of people, regardless of gender identification. So to what extent does the desire to rape or be raped motivate such fantasies? Clearly, no one can desire to be raped as it belies the very definition of rape. But what about those people who have sexual fantasies in which they are the rapist? It can be contended that such people, generally unaware of extant social pressures, are motivated by the social factors that result in gendered oppression and violence, but use the fantasy as an outlet so as not to transgress socio-cultural mores. The argument goes that much like the pedophile who opts to watch child pornography or animated renderings of sexual liaisons with underage persons, those who fantasize about rape (in a consensual manner) possess within them the capacity to commit rape. What prevents them from doing so is their socio-political beliefs, thus substituting the consensual encounter with a willing partner for the “real thing.”

East Pakistan led to a mass exodus of refugees into India. Despite an international outcry, the assaults and rapes continued – Credit by Raghu Rai.

It is imperative to understand that those who have sexual fantasies wherein they are the rapist are not actively seeking to rape others, using the fantasy as a stop gap. Rather, subconsciously they are prepared to commit rape but are prevented by their consciousness of socio-sexual relations. So this isn’t so much an issue of cognitive dissonance as it is of subconscious desire versus conscious actions. The problem of rape fantasy and desire is in fact the social realities which allow such desires to manifest (consciously as well as unconsciously) rather than the existence of such desires in and of themselves.

Rape fantasies are surprisingly common among both women and men. It is difficult to accurately determine the prevalence of rape fantasy, as studies depend on self-reporting techniques, which are influenced by multiple factors such as time, place, and the wording of questionnaires. According to several studies conducted over the course of four decades, around half of women have had rape fantasies. Additionally, through more nuanced methodologies, it was ascertained that some women feel both fear and arousal in response to rape fantasies. Furthermore, in these studies, women mostly react positively to thoughts of erotic “rape” and negatively to thoughts of actual rape. Therefore, there is a clear boundary between wanting to act out a rape fantasy and wanting to actually be raped.

Unfortunately, there are limited statistics on women wanting to commit rape as well as on men wanting to engage in a rape fantasy as either participant. However, it is safe to assume that there are groups within every gender identity who fantasize about being a “rapist,” about being “raped,” and about playing both roles in a rape fantasy, as well as those who do not have rape fantasies of any kind.

It is important to emphasize that just as a desire to engage in a rape fantasy is not equivalent to a desire to be raped, a desire to act out a fantasy in which one is the “rapist” is not equivalent to a desire to actually rape. To equate the appetite for rape fantasies with a propensity to commit actual rape, citing “unconscious desires” as the cause of these fantasies, is to call upon antiquated Freudian notions of the conscious and unconscious mind. Freud believed that the mind was separated into three parts: the id, the ego, and the superego. The id is supposed to be the seat of unconscious desires and neuroses, the superego is the “moral” part of the mind, and the ego is the mediator between the two. This theory has been widely criticized and disproven. In fact, what is commonly called the “conscious” mind is the part of the mind that one is attending to at any given point in time, and the “unconscious” mind is simply the part of the mind that one is not paying attention to.

Therefore, there are no “unconscious desires” driving human behavior, merely motivations that are largely caused by the sexist, racist, or classist attitudes and behaviors engendered by the sexist, racist, and classist capitalist society in which this discussion takes place. The actual desire to oppress women, especially women of color and working-class women, is by no means “unconscious” – it is very much out in the open, even as it is actively ignored, misunderstood, or mischaracterized by the collective consciousness. To attribute the desire to act out a rape fantasy to “unconscious desires” spawned by oppressive gender roles is not only scientifically inaccurate, but it is also simply foolish to assume that simulating problematic human behaviors such as rape in a consensual context necessarily stems without exception from the expression of these desires. Although rape is a tool for the oppression of women, rape fantasies are not, at least not inherently.

There are many explanations for the apparent frequency of rape fantasies. The occurrence of rape fantasies could be attributed to having masochistic or sadistic tendencies, avoiding sexually motivated blame or guilt by being powerless in a sexual situation, and wanting the “rapist” to find an individual so sexually appealing that they just cannot help themselves. Additionally, the power dynamic inherent in rape can be explored in a safe and empowering way. Instead of seeing rape fantasies as a fraught way to channel one’s desire to rape or be raped, feminists and other proponents of women’s liberation might acknowledge that both taking power and choosing to resign power can be empowering. Rape fantasies can be used as a method to reclaim power over one’s body after a sexual assault or in response to the ubiquitous threat of sexual assault, a way to reenact a situation in which one’s power is involuntarily stripped as one in which power is voluntarily surrendered power to a trusted partner. In this way, acting out a rape fantasy could even become a therapeutic tool.

Some of these underlying motivations may very well stem from the problematic societal proclivity to commit violence against women. However, this is not always the case – few would argue that a predilection for sadistic or masochistic sexual tendencies, while often manifested in a harmful way in the form of gendered violence, necessarily stems from the desire to commit gendered violence. In short, the desire to commit actual rape is a symptom of women’s oppression, and it is abhorrent that this desire exists on such a widespread scale and that it is systemically facilitated by the oppressive society that now exists. Be that as it may, it does not logically follow that the desire for rape is driving the existence of rape fantasies or the desire to act out those fantasies.

Capitalism, Feminism, and Rape Fantasy

Rape is only one way in which women are oppressed in capitalist society. While rape as a socio-political phenomenon is rooted in the subjugation of women, that does not mean that the desire to simulate rape with a willing partner necessarily stems from the desire to participate in the socio-political oppression of women. Similarly, there are many other behaviors that are rooted in the oppression of women under capitalism. For example, wearing dresses, high heels, and elaborate makeup; behaving in a certain way around men in professional, social, and romantic or sexual contexts; and the act of sex itself are all ways in which women navigate a male-dominated world. Does this mean that women should eschew all such behaviors, citing their problematic roots? Is it necessarily problematic to be attracted to women who dress in a certain way or who wear nail polish, if these are indicators of society’s problematic approach to female behavior? It is absurd to argue that any behavior with origins in the oppression of women is always necessarily problematic.

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO. GOMA. December 12, 2013. Hamida waits in her home for clients to arrive. Hamida, 26, is a sex worker living in Benghazi, a neighborhood in the city of Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo (D.R.C.). She moved there in 2002, when nearby volcano Mount Nyiragongo erupted and destroyed her home in Berere. Benghazi, a slum of wooden shacks built atop lava rock, was named after the city of Benghazi, the Revolutionary base during the Libyan Civil War, as it is a place of “fighting and crying.” Many residents are prostitutes and their families. Upon arrival, she roomed with other sex workers to save money. She now has two rooms and pays $30 per month.

Of course, under capitalism, a system that integrates the oppression of women, people of color, and working-class people into everyday life, it is more difficult to parse whether a certain desire or action is problematic. For example, do men find women who wear nail polish attractive because of the sexist expectation of female beauty or is it genuinely an individual’s appreciation for the aesthetic? One must acknowledge that even sex between consenting adults, because of the slew of potentially problematic behaviors that come along with this, is itself never politically innocuous. Sex as it is understood and performed today has not only biological but also social origins and meanings; socially accepted sex today—heterosexual sex within a monogamous relationship—is the norm because of the material realities of the society that underpin it; it is contaminated with the social and political problems of our times. For this reason, it is difficult to ascertain whether a certain sexual situation is problematic. Similarly, one cannot say wholesale that rape fantasies are necessarily problematic under capitalism. While some rape fantasies have roots in actual rape, it doesn’t mean an individual’s desire to engage in those fantasies necessarily stems from the societally-motivated misogynistic inclination to rape.

So then, to what degree can feminism, in its various permutations, offer an ideological scaffold to understand the phenomenon of rape fantasy? And furthermore, to what extent will a remedy to the woman question effect the prevalence and qualitative nature of rape fantasies? Neither of these queries are readily answerable, the former due to the lack of cohesion amongst the ideologies of what constitute feminism, and the latter due to the limitations of the current political imaginary. Notwithstanding that, feminism(s) and the political issues around the woman question can offer, at the very least, an insight into the potential futures of rape fantasy.

Bourgeois feminism would posit one of two things. Either rape fantasy is the result of the societal oppression of women by men (an idealist formulation which while possibly accurate in some cases fails to account for the material basis of women’s oppression); or in an extremely noxious liberal fashion that holds little regard to broader societal processes and existing social relations, that all unto the individual is fine so long as it hurts no one else. Both these answers are insufficient given the near equal prevalence of rape fantasies across gender lines and that clearly, thoughts as well as actions, whilst not hurting someone, can still be quite problematic. The so-called Third Wave feminism of the 1990s and its emphasis on “intersectionality” would likewise conceive of some hierarchy based on identity wherein certain groups would be seen as more appropriate or less problematic when harboring fantasies about rape. In effect, feminism, as a broader ideology, is incapable of understanding rape fantasy outside of the confines of the capitalist social structure.

And as it relates to the woman question, and specifically women’s liberation (including LGBTQ liberation) not under capitalism but through its destruction, what then of rape fantasy? Certainly, it won’t cease to exist as a phenomenon amongst humans. But it is possible that in a post-capitalist social order, wherein non-men are equitable members of society, the social desire to rape would be tempered. However, the biological imperative to reproduce would still exist. Said another way, if rape fantasy currently exists due to social relations around gender, it can be excised from the psyche once gender equality exists. But with no possible way of overcoming biological differences between males and females (as opposed to gendered difference between women, men, and others), the desire to rape, manifested as the overwhelming desire to reproduce, would likely still exist, albeit as a much less common social phenomenon. The rape fantasy in a post-capitalist society, motivated by biological determinants rather than social relations of power, would be far less problematic both in terms of its manifestation as desire and its enactment between sexual partners. Additionally, the occurrence of biologically motivated rape will be greatly diminished as adequate education and social conditioning in a post-capitalist society enable individuals to overcome this biological imperative. Therefore, in a society where non-men, and women in particular, are not systemically oppressed by the dominant social group, rape will become exceedingly rare.

The Ethics of Rape Fantasy

In a sexist, racist, and classist society, rape is all too common. It manifests as a tool by which women are oppressed, and women of color and working-class women are especially affected by this systemic injustice. Rape fantasies can occasionally be a way for would-be rapists to act out their desires in a less problematic manner. However, this is not always the case. There are a multitude of other reasons for acting out a rape fantasy, both as the “rapist” and “victim.” It can be generally agreed that rape fantasies are influenced by socially mediated factors. However, under capitalism, it is difficult if not impossible to parse whether rape fantasies necessarily originate from the desire to rape. In a situation in which rape fantasy occurs among consenting participants and does not contribute to social acceptance of the phenomenon of rape, it would become simpler to accept it as a mere individual sexual preference. Unfortunately, once social and political factors come into play, which is invariably the case, it is difficult to ascertain whether a certain phenomenon or behavior is ethical. And what can be considered socially ethical (as opposed to an individual’s ethical considerations) save for those promulgated by the upper strata of society? Just as one does not provide material resistance to factory farms by buying local produce, one does not affect the oppression of women by condemning or supporting rape fantasy. Rape fantasy is a mere symptom and not a cause of the oppression of women and biological females, and so there is no material basis upon which one can isolate and target the ethics of rape fantasies as a social phenomenon.

Rape.Rapist.Rapier. Disarm. Comply. Recognize others,..not out of fear or blame. The desirable becomes the undesired not the undisreable for it is not enough. Human endeavor is not consequence,..it is arriving. It is surpassing not overcoming. It is more than an interlude. It is more than our deep dismay. We all wait for an answer to stop violence. We need to listen to our clenched fists of frustration as we wait for better tomorrows. We arrive together. As one.