Curtis Russell

When Alien hit theatres on May 25, 1979, the United States was up to its dugs in its second energy crisis in a decade. Three Mile Island had just gone ass over teakettle, Idi Amin was on the run, and a freshly elected Margaret Thatcher was kicking off her Decade of Fun in the UK. Jimmy Carter’s “Crisis of Confidence” speech, which would famously change nothing and, with the Iran hostage crisis, kill Carter’s political future deader than disco was about to be, was just a few months down the pike. Into this morass sailed the USCSS Nostromo with its intrepid crew of hardasses, fusing the space grit of Star Wars with the working stiffs of 1978’s Blue Collar to create a new kind of proletarian space horror.

When Alien hit theatres on May 25, 1979, the United States was up to its dugs in its second energy crisis in a decade. Three Mile Island had just gone ass over teakettle, Idi Amin was on the run, and a freshly elected Margaret Thatcher was kicking off her Decade of Fun in the UK. Jimmy Carter’s “Crisis of Confidence” speech, which would famously change nothing and, with the Iran hostage crisis, kill Carter’s political future deader than disco was about to be, was just a few months down the pike. Into this morass sailed the USCSS Nostromo with its intrepid crew of hardasses, fusing the space grit of Star Wars with the working stiffs of 1978’s Blue Collar to create a new kind of proletarian space horror.

Star Trek this was not. With its campy, utopian outlook, Star Trek envisioned a distant future where humankind, having learned to live together in harmony, spread its groovy message of peace and love with Pentecostal zeal throughout the galaxy (or at least as far as the Neutral Zone). Alien took a much bleaker stance, anticipating in the not-quite-as distant future a human race that had cooler gear but was just as exploitative, technocratic, and stratified as ever.

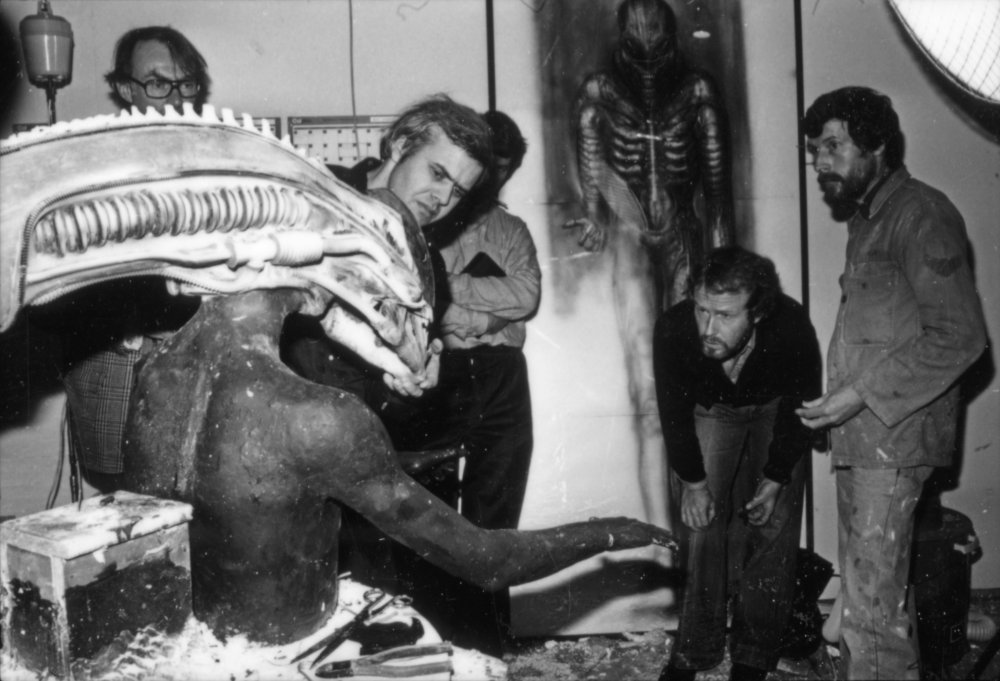

H.R Giger, Ridley Scott and crew inspect model during production for Alien (1979) – Source: http://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/news-bfi/features/hr-gigers-alien-in-pictures

Alien, in fact, has much more in common with Blue Collar than with Star Wars/Trek. The directorial debut of Paul Schrader, screenwriter of Martin Scorsese’s feel-lousy classic Taxi Driver, Blue Collar holds a dim view of labor relations. Both management and union heads are abusive, corrupt, and more than willing to sell out or liquidate the film’s auto workers, played by Richard Pryor, Harvey Keitel, and Yaphet Kotto. If there’s one thread running through the first four Alien films’ queasily phallic nightmarescape, it’s the similarly maniacal obsession of the shadowy multigalactic Weyland-Yutani Corporation to get their greedy hands on a Xenomorph alien, regardless of the cost to the peons doing all the work. As in so much of the best science fiction, this bottom-up, anti-corporate view of labor not only gives the films a rich metaphorical texture, it also grounds their more outré elements. In other words, it’s easier to accept the following scenario from the climax of 1997’s Alien: Resurrection, the series’ fourth installment, if you can see it as the inevitable result of corporate malfeasance: a white monster gets sucked spine-first into space through a little hole made in a window by the acid blood of its weeping human grandmother, a clone of a woman who, after being face-impregnated 200 years previously by an alien, committed suicide by Golluming into a fiery furnace to prevent the aliens’ dissemination. Or something. Even though the series eventually jumped the Xenomorph, neglecting its blue-collar roots in favor of glossy, convoluted mythology, it began life as a claustrophobic Agatha Christie-in-space chiller about seven hirelings scared shitless by a tough little son-of-a-bitch who just wants to play hide and seek.

The very first words in Alien deal with labor relations. They are spoken by none other than Yaphet Kotto, his irascible Blue Collar workhand imported seemingly intact, headband and all. Even though they do the “real work,” Kotto’s Parker, the Nostromo’s chief engineer, and Harry Dean Stanton’s Brett, the engineering technician, are aggrieved by their draconian contract—they only receive a half-share to the rest of the crew’s full share for their current job, hauling ore back to Earth. They’ve got no leg to stand on, of course, having signed the contract. Later, they try to evoke the same contract as protection when Dallas (Tom Skerritt) makes the maybe-not-great-in-hindsight decision to trace the source of the distress beacon on LV-426. Dallas cites the pesky small print, and they begrudgingly concede. At one point, Parker and Brett even half-assedly threaten to strike. “Don’t worry Parker, you’ll get whatever’s coming to you,” Sigourney Weaver’s warrant officer Ellen Ripley warns them while pulling on a t-shirt that reads “Dramatic Irony” in big sequined block letters. They argue that diverting from their mission isn’t standard procedure. “Standard procedure is you do what the hell they tell you to do,” Dallas replies, ever the rugged company man. (We know he’s rugged because he has a beard.)

The very first words in Alien deal with labor relations. They are spoken by none other than Yaphet Kotto, his irascible Blue Collar workhand imported seemingly intact, headband and all. Even though they do the “real work,” Kotto’s Parker, the Nostromo’s chief engineer, and Harry Dean Stanton’s Brett, the engineering technician, are aggrieved by their draconian contract—they only receive a half-share to the rest of the crew’s full share for their current job, hauling ore back to Earth. They’ve got no leg to stand on, of course, having signed the contract. Later, they try to evoke the same contract as protection when Dallas (Tom Skerritt) makes the maybe-not-great-in-hindsight decision to trace the source of the distress beacon on LV-426. Dallas cites the pesky small print, and they begrudgingly concede. At one point, Parker and Brett even half-assedly threaten to strike. “Don’t worry Parker, you’ll get whatever’s coming to you,” Sigourney Weaver’s warrant officer Ellen Ripley warns them while pulling on a t-shirt that reads “Dramatic Irony” in big sequined block letters. They argue that diverting from their mission isn’t standard procedure. “Standard procedure is you do what the hell they tell you to do,” Dallas replies, ever the rugged company man. (We know he’s rugged because he has a beard.)

Alien is so committed to its drab vision of democratically shitty space travel that Ripley emerges as the hero almost by process of elimination. There are no early “hero shots,” nothing to clue us in that Ripley is the one to root for. As far as we know, she is just another cranky space jockey. Director Ridley Scott claims that this gender reversal from the original script was meant to play on audience expectations for beautiful women in horror films, but it does something much more canny and interesting as well—it disseminates our empathy among the whole ensemble. They’re all assholes (with the exception of John Hurt’s first-to-burst Kane), and with no clear protagonist, it’s easy to believe no one will make it. That the reversal produced the most kick-ass screen heroine of the last 40 years was just the cream.

Alan Dean Foster took a different but equally fascinating approach to character development in his Alien novelization. Just look at his bonkers first paragraph:

Seven dreamers. You must understand that they were not professional dreamers. Professional dreamers are highly paid, respected, much sought-after talents. Like the majority of us, these seven dreamt without effort or discipline. Dreaming professionally, so that one’s dreams can be recorded and played back for the entertainment of others, is a much more demanding proposition. It requires the ability to regulate semiconscious creative impulses and to stratify imagination, an extraordinarily difficult combination to achieve. A professional dreamer is simultaneously the most organized of all artists and the most spontaneous. A subtle weaver of speculation, not straightforward and clumsy like you or me. Or these certain seven sleepers.

Now that’s an opening. Foster is defining a wicked-sounding job called “prodreaming,” which I imagine as some cool futuristic filmmaking technique where the images are pulled directly from the artist’s consciousness, probably over Bluetooth. Though it goes about it differently than the film, this opening manages a similar trick of engendering the reader’s empathy by implying that she’s just like the Nostromo’s regular schlubs, “straightforward and clumsy.”

Foster doesn’t repeat the movie’s slow-reveal trick though, instead giving Ripley immediate pride of placement: “Of them all, Ripley came closest to possessing that special potential. She had a little ingrained dream talent and more flexibility of imagination than her companions. But she lacked real inspiration and the powerful maturity of thought characteristic of the prodreamer.” The other characters are also defined by their capacity to prodream. The more creative their dreaming ability, the higher their standing. It’s a bizarre but ingenious way to define the world’s power dynamics by drawing a direct line between station and ability (even if it assumes that every member of the crew is in the position they deserve) and classifying labor as its own peculiar dream. The dreaming motif reappears in other Alien novelizations, just as several films in the series begin with a sort of reverse “awakening” from cryostasis into the nightmare world for both the characters and the viewer.

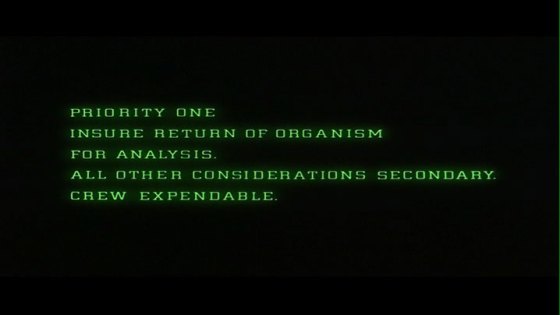

One thing is certain: regardless of these skilled laborers’ ability to prodream and/or rock a sweet Barry Gibb beard, to “The Company,” as Weyland-Yutani is portentously called throughout the series, they’re little more than alien chum. Science Officer Ash, only too happy to sacrifice a crewmate or three to preserve the Xenomorph, is eventually revealed to be an android (no spoiler alerts here; the statute of limitations expired on this movie about 37 years and 11 months ago), planted by the company to ensure strict observance of their mandates. Ian Holm, always robotic, cold, and affect-less, was perfectly cast in the role that established an important archetype in the Alien-verse: the company stooge. Generally speaking, the doomed crews in each film would have a much higher survival rate, if not for the scab in their midst sacrificing them for The Company’s sake or personal gain (like Paul Reiser’s greasy Burke in Aliens). Ash lets the infected crewmembers back on the ship when Ripley wants to keep them in quarantine. He communicates directly with The Company through Mother, the ship’s OS, and tries to kill Ripley when she discovers The Company’s endgame, unfolding across the screen in late-70s computery neon green bleeps and bloops:

Priority one

Insure return of organism

For analysis.

All other considerations secondary.

Crew expendable.

Well, shit. Smoke ‘em if you got ‘em.

1986’s Aliens trades space roustabouts for space Marines. The dialogue, a constant one-upmanship to see who can be the biggest jagweed, appears to be written by someone who never met an actual Marine. That writer/director is, of course, James Cameron, who was fresh off The Terminator and would go on to direct the two highest-grossing films of all time, Titanic and Avatar. In 1986, he was only King of the World in his own head so, despite some delightfully dodgy dialogue (“Game over, man!”), Aliens still feels handmade and human.

The film takes place 57 years after the events of Alien. While Ripley and Jonesy the cat have been floating in cryostasis, Weyland-Yutani has stepped up its colonial game and sent dozens of families to LV-426 to terraform and mine. The Company’s motto is “Building Better Worlds,” but it might as well be “Make Space Great Again,” for all its naked avarice in exploiting the galaxy’s natural resources. Naturally, things go pear-shaped, and Ripley is coerced into accompanying the Marines back to the planet.

Following the first rule of Sequel Club, “More is more,” Aliens introduces dozens of new beasties and plenty of grunts to sacrifice to them, though it is less interested than its predecessor in challenging hierarchies. The grunts bitch and moan, but any breakdowns are the fault of a few bad eggs, not the military system. The film does replicate Alien’s strategy of the slow reveal, so we only gradually realize that Michael Biehn’s Hicks is this pack’s designated survivor. Ripley is still the hero of course, and saves the day (and her new daughter, Newt) with her “Class 2 rating” power loader abilities—the triumph of skilled labor. And this time, when the spacedust settles, Ripley is rewarded with a little family unit all her own: Hicks, Newt, and Bishop (Lance Henriksen), the #notallandroids robot who turned out to be pretty chill after all.

Don’t get too cozy, though. Even Jonesy the cat survived the first film, but Ripley is the only member of this makeshift family unit to make it to 1992’s relentlessly grim Alien 3, my personal favorite. Director David Fincher (Se7en, Fight Club, Gone Girl) has famously more or less disowned the picture, his first, but with all due respect, he doesn’t know what the hell he’s talking about. Though the least thrilling entry in the franchise and not Fincher’s best film (that would be Zodiac), it’s much better than he acknowledges, complicating the narrative with that old bugaboo, religion.

The flavor on tap is an “apocalyptic, millenarian, Christian fundamentalism” that would feel right at home in America, 2017. Its practitioners are the skeleton crew occupants of Fiorina “Fury” 161, a maximum security “Double Y Chromosome Work Correctional Facility” planet that doubles as an ore refinery run by—you guessed it!—Weyland-Yutani. These bar-coded prisoners, whose genetic mutation makes them prone to violent crime, have turned to Jesus to ensure harmony, which Ripley upsets when her pod crashes on their beach. Religion truly is their opiate; though the prisoners are by far the most “alien”-ated group of exploited workers in the series, they’re also the most complacent. Their flea-infested, dank, and miserable penal colony, which prefigures the underground Zion of the Matrix, serves only to humble them at the feet the “angry god” they pray to. Ripley (“ripple-y”) doesn’t just upset the harmony; she bears God’s judgment.

The less said about Alien: Resurrection, the nippled Bat-suit of the franchise, the better. The working stiffs are still there, but by now Ripley is a cloned superhero basketballer. (Remember, in the 90s, everyone wanted to Be Like Mike.) The film mistakes misanthropy for character depth, so the more interchangeably cantankerous peons die, the lighter and better the film gets, although any lingering crumb of credibility is ejected into the void with the above-mentioned half-human space yeti. We do learn, however, in the series’ best joke, that Weyland-Yutani was eventually bought out by Wal-Mart. Except for the 2004 spinoff AVP: Alien vs. Predator and its lame 2007 sequel, AVP: Requiem, the Alien franchise was functionally deceased, and few lamented its passing.

Hope was high, however, when Fox announced Prometheus, Ridley Scott’s allegedly non-Alien prequel that everybody knew was an Alien prequel. The 2012 film turned out to be less a brilliant new monster bursting from the chest of the Alien franchise’s bloated corpse than a dead facehugger falling to the floor with a dry thud. Scott, et al. apparently learned nothing from the mistakes of George Lucas’s kitschy Star Wars prequels, opting for convoluted myth making and Guy Pearce in old dude makeup. The result was slick, shiny, and boring as hell, wasting two great central performances from Noomi Rapace (who never got the Hollywood break she deserved) as Dr. Elizabeth Shaw and Michael Fassbender as the requisite Android With Questionable Motives™. Though the prequel was a non-starter, it apparently earned enough ducats to justify a prequel-sequel, and this summer saw the release (and quick departure) of the even flatter Alien: Covenant.

Hope was high, however, when Fox announced Prometheus, Ridley Scott’s allegedly non-Alien prequel that everybody knew was an Alien prequel. The 2012 film turned out to be less a brilliant new monster bursting from the chest of the Alien franchise’s bloated corpse than a dead facehugger falling to the floor with a dry thud. Scott, et al. apparently learned nothing from the mistakes of George Lucas’s kitschy Star Wars prequels, opting for convoluted myth making and Guy Pearce in old dude makeup. The result was slick, shiny, and boring as hell, wasting two great central performances from Noomi Rapace (who never got the Hollywood break she deserved) as Dr. Elizabeth Shaw and Michael Fassbender as the requisite Android With Questionable Motives™. Though the prequel was a non-starter, it apparently earned enough ducats to justify a prequel-sequel, and this summer saw the release (and quick departure) of the even flatter Alien: Covenant.

Though the specifics differ, the story is familiar. The Covenant is hauling colonists instead of coal. Android Walter (Fassbender, pulling double-duty) wakes the crew early when the ship is damaged by the shockwave from a new star forming. One of the sleeping pods malfunctions, barbecuing the captain (James Franco, for some reason). When the crew detects a transmission from a nearby planet, de facto captain Christopher Oram (Billy Crudup) wants to check it out. The crew, including obligatory Ripley surrogate Daniels (Katherine Waterston, who, between this and last year’s Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, is fast becoming queen of the mediocre franchise reboots), protest but, well, I’ll give you one guess where this is all heading…

This time out Scott and his team were clearly paying attention to the more-successful 2015 Star Wars reboot, co-opting The Force Awakens’ tactic of loosely remaking the first film with better effects, to equally mixed results. The original Alien is great because it takes its time. We don’t care because it’s on a spaceship, we care because a small group of people we’ve been given time to befriend are getting screwed by the very company that put them in harm’s way. Alien: Covenant has no time for such fripperies. It’s in too much of a hurry to get to all the blood and guts and kung fu aliens (yes, you read that right). So it’s not long before we’re introduced to the white-skinned Neomorph, which, in as clever a twist as the film is capable of, bursts out of a character’s back instead of his chest.

Luckily, Alan Dean Foster, who must be about 137 by now, is on hand to remind us what the series once was. He introduces his Alien: Covenant novelization with dreaming, or rather, its absence:

It wasn’t dreaming. It did not have the capability. The omission wasn’t intentional, not deliberate. This was simply a known consequence of its creation. Where it was concerned, the intention was that there should be no surprises. In the absence of an unconscious consciousness there could be no abstract conceptualization. The speculative information dump necessary to allow for dreaming was absent. Yet—there was something. Difficult to define. Ultimately, only it could define its own state of non-being. Only it could understand what it did not know, did not see, did not feel.

He’s talking about Michael Fassbender’s David, the only character to survive Prometheus. The abstruse prose reveals just what a knot the series has gotten itself in. Not only are the robots now the most interesting characters (not necessarily a problem per se), no one can figure what the hell these stories are even saying anymore. Missing from all the talk of “unconscious consciousness” and the Fassbender-on-Fassbender fistfights is the David-and-Goliath imbalance that made the Weyland-Yutani Corporation the series’ true big baddie. In their sinewy menace, the Xenomorphs are the devils you know. The Company, on the other hand, is distant, amorphous, spectral. Minus that threat, all that remains are the aliens, and they haven’t been particularly scary or compelling since they stepped out of the shadows as demented CGI schnauzers in Alien 3. The graphics have gotten better, but the wow is MIA. Our political moment is just as fractured as Alien’s, and we need to be told that the little guy still has a chance, even if it’s a lie. All Alien: Covenant has to offer is the mute spectacle of a franchise that hasn’t had anything on its mind for 25 years.

Game over, man.