Erik Wallenberg

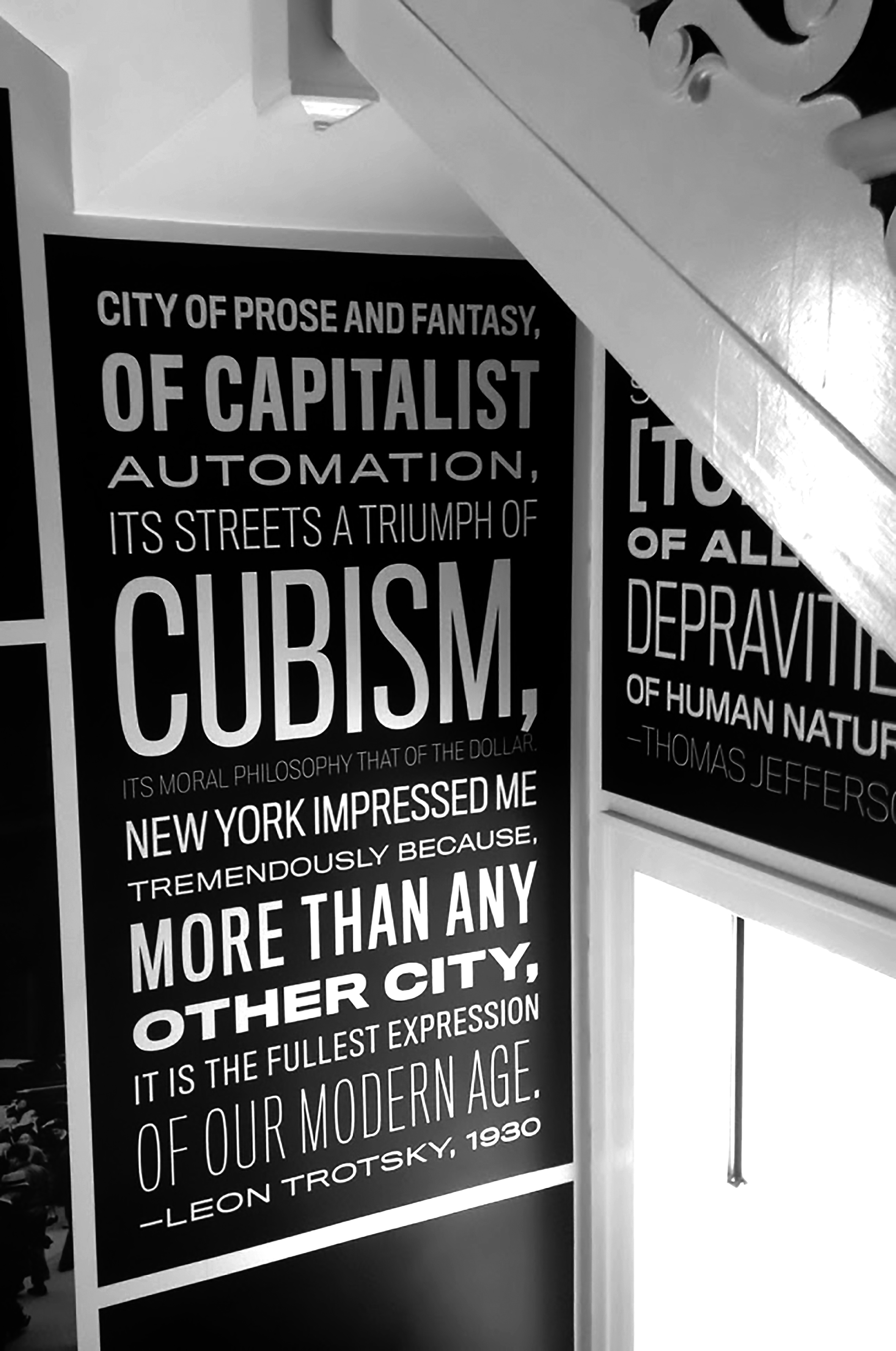

One can stand in the stairway at the Museum of the City of New York surrounded by quotes stenciled on the walls which pay homage to the metropolis. One quote that dominates the wall reads, “New York, city of prose and fantasy, of capitalist automation, its streets a triumph of cubism, its moral philosophy that of the dollar.” Leon Trotsky wrote these words remembering his time in New York in the early days of 1917. He “only managed to catch the general life-rhythm of the monster known as New York” because he had to hurry back to Russia.

One can stand in the stairway at the Museum of the City of New York surrounded by quotes stenciled on the walls which pay homage to the metropolis. One quote that dominates the wall reads, “New York, city of prose and fantasy, of capitalist automation, its streets a triumph of cubism, its moral philosophy that of the dollar.” Leon Trotsky wrote these words remembering his time in New York in the early days of 1917. He “only managed to catch the general life-rhythm of the monster known as New York” because he had to hurry back to Russia.

The events that unfolded in Russia over the course of the year 1917 had been anticipated and dismissed in equal measure over the previous decades. The feudal monarchy of the Romanovs was long past its prime while the socialist movement innovated new forms of democracy as late as the crushed rebellion of 1905. The fall of the centuries-old tsarist regime in February as well as the socialist revolution that came in late October were followed around the world by supporters and detractors alike.

New York was home to a vibrant socialist and radical Left that welcomed the news of the October revolution with open arms and big expectations. In January 1918, the socialist newspaper the New York Evening Call sent “heartiest greeting” to the new socialist government in Russia “who so valiantly uphold the principles of international Socialism.” Concern over ending the slaughter of the World War while protecting weaker nations was foremost on the agenda. The Evening Call proclaimed to its readers, “We are highly gratified over the fact that the first Socialist government ever established has brought about the beginning of peace negotiations and was instrumental in forcing the imperialistic world powers and their capitalistic governments to pay homage, in words if not deeds, to the Socialist peace formula of: No annexations, no punitive indemnities and the self determination of nationalities.” The orgy of death and mutilation that marked the trench warfare of World War I is central to understanding the history of 1917. Ordinary soldiers were essential to the war, as they are to all wars, and accordingly, China Miéville keeps them at the foreground of his history of the two revolutions in Russia that year.

The hated war and the soldiers fighting on the front, along with their families bearing the burden of scarcity, uncertainty, and fear at home, was the cauldron in which this revolution was forged. October is mostly the history of “the crucible of the revolutions,” the city of Petrograd. It was a cosmopolitan city, one where a variety of languages, European and Asian, were heard in the streets. “Around its wealthy heart” Miéville writes, “it was a city of workers, swollen by the war to around 400,000, an unusual proportion of them relatively educated. And it was a city of soldiers, of whom 160,000 were stationed there in reserve, their morale poor and getting worse.”

As a primer, Miéville takes us through a masterful sweep of 400 years of Russian history to get us to the Marxists who are “a gaggle of emigres, reprobates, scholars and workers, in a close weave of family, friendship and intellectual connections, political endeavor and polemic. They tangle in fractious snarl. Everyone knows everyone.” Among this group we learn that belief in the possibility of a socialist revolution is muted, as one Marxist states, “There is not yet enough proletarian yeast in Russia’s Peasant dough to make a socialist cake.” Miéville shows the problems faced by those wanting to make a revolution in a country with a peasant majority and a bourgeoisie with little will to overthrow the monarchy. The best they can manage is, in Miéville’s formulation, “Political activism through passive-aggressive dinner parties.”

The revolutions don’t, however, materialize from these corners of Petrograd. It all begins with the women who walked off their jobs on International Women’s Day, demanding bread and peace, on a cold February morning. The women agitated for the men to come out too. Fraternizing with soldiers on duty, they attacked police who they referred to as ‘Pharoah,’ an identification that would stick. The revolutionaries struggled to catch up with this growing rebellion that quickly began to challenge the centuries’ old system of rule. The women “stormed prisons and tore open doors and freed the bewildered inmates.” Meanwhile the tsar and his ministers remained unconvinced of the seriousness of the rebellion.

The revolutions don’t, however, materialize from these corners of Petrograd. It all begins with the women who walked off their jobs on International Women’s Day, demanding bread and peace, on a cold February morning. The women agitated for the men to come out too. Fraternizing with soldiers on duty, they attacked police who they referred to as ‘Pharoah,’ an identification that would stick. The revolutionaries struggled to catch up with this growing rebellion that quickly began to challenge the centuries’ old system of rule. The women “stormed prisons and tore open doors and freed the bewildered inmates.” Meanwhile the tsar and his ministers remained unconvinced of the seriousness of the rebellion.

Miéville paints the scene they missed: “In the boulevards of the insurgent city, revolutionary socialists jostled alongside angry liberals and all shades in between, and they were not calm. What they shared was a certainty that change, a revolution, was necessary…Under the darkening sky, accompanied by breaking glass and in the guttering light of fires, groups of men and women drifted aimlessly together and apart, workers, freed criminals, radical agitators, soldiers, freelance hooligans, spies and drunkards. Armed with what they had found. Here, a figure in a greatcoat waving an officer’s sabre and an empty revolver. There, a young teenager with a kitchen knife. A student with machine-gun bullets slung around his waist, a rifle in each hand. A man wielded a pole for cleaning tramlines as if it were a pike.”

The Councils of Workers and Soldiers, the Soviets, were thrown up by the revolutionary actors themselves as locations for democratic decision making. An innovation of the working class from the last failed revolution of 1905, the Soviets became the central location and site of power to challenge the status quo. The tsar had offered a “concession” to the demand for democracy in the form of a powerless “representative body,” the Duma.

In the midst of the revolution, Miéville tells us that the Mensheviks “made straight for the corridors of power,” that is, for the Duma and new Provisional Government. The Bolsheviks, on the other hand, headed to the workers’ districts. It’s this crucial difference in the orientation of the various socialists and their organizations that comes up time and again; some focus on established institutional bourgeoisie sites of power to make change, while others look to those who make the society function, the working class.

Soviet leaders on November 7, 1919, in Red Square, Moscow, USSR, celebrating the second anniversary of the October Revolution. L.Y. Leonidov – Credit: Wikimedia

With the hard right in disarray and the Soviets tepid in their approach, keeping a “watchfulness” and “vigilant control” over the Provisional Government, Lenin argued the hard line of continual revolution. Most centrally, Lenin argued for fraternization at the front while everyone else seemed to call for a continuation of the war as “revolutionary defencism,” that is support for the war as defense of the new revolution. Miéville notes that with this call for fraternization at the front Lenin was dismissed as ‘a has-been’ and his ideas as ‘political excesses,’ ‘lunatic ideas,’ and ‘the ravings of a madman.’ At points like this, which slip into the “great-man” view of history, I wonder how alone Lenin really was. Why do we never get voices of the other committee members who agreed with him? Or better yet, the Bolsheviks and others in the Soviets or the soldiers themselves, calling for an end to the war. Is there no record of anyone else? Did he argue all alone? Miéville mostly steers clear of sanctifying the players in his story, and Lenin does come up for plenty of criticism. And yet in moments like these, Lenin seems to be a singular miracle from above. Miéville hints at this when he describes few speakers taking Lenin’s position in the formal debate, only to win the vote. Miéville says with a wink: Lenin “must have had a good deal of shy support.”

The socialists were a motley crew. Those from the various factions and splits of previous organizations, including Bolsheviks, Mensheviks, Socialist Revolutionaries, and more still moved between groups and spoke for and voted for each other’s resolutions. Miéville follows many of those known and familiar figures such as Maxim Gorky, Alexandra Kollontai, Vladimir Lenin, Julius Martov, and Leon Trotsky.

We are treated to a memorable cast of characters including “Shlema Asnin, a respected militant with the First Machine Gun Regiment, a dark-bearded former thief who dressed like a gothic cowboy, wide-brimmed hat, guns and all.” Unfortunately, we don’t follow figures like Asnin, and instead trail a familiar coterie around Lenin. It can seem at times that all was lost without Lenin. To be sure Miéville never says these words, and in fact he notes that he doesn’t think that’s the case, but what he writes at times seems to suggest that still.

Miéville does show a broader Bolshevik Party in his book as well. In the back and forth of the July days, the Bolsheviks sponsor a concert to raise money for anti-war literature for soldiers to take with them to the front. The focus on turning the tide of the war, and the confidence with which it was carried out, were hallmarks of the Bolshevik rank-and-file.

The ruling class meanwhile put its trust in the military generals. Miéville sets the scene of General Kornilov’s rise as “an ecstatic upper-class crowd” sends a “shower of petals” raining down on the hoped-for dictator’s head. Backed by money, Kornilov’s first meeting is with the Society for the Economic Rehabilitation of Russia, a right-wing business group, backed by individuals who “went so far as to offer funds specifically for an authoritarian regime.”

But power lay with the organized working class of Petrograd. A committee of soviets made sure that ‘suspicious telegrams’ be held and troop movements be tracked while transport workers aided the work of the soviet and refused to carry those working against the revolution. When the head of the Provisional Government tried to shore up his authority by ordering the Sailors of the Baltic Fleet to disband their soviet, the sailor’s response was “simply that his order was ‘considered inoperative.’”

The book is set up with each chapter as a month of the revolutionary year, and the novelistic features of the book are especially strong in the final chapter, ‘October.’ One of Miéville’s stated aims is to tell this oft-told history as a story, and early chapters have a literary quality that draws the reader into the action. In some cases Miéville matches and even exceeds this charge. His stories of a big-wigged Lenin buying a disguise and his befuddled wigmaker telling tales for a long time after “of the youngish client who had wanted to look old” are entertaining. And his writing is both rich and at times comic, as in his memorable joke about the hated monarch Nicholas and his “placid tsarry eyes.” However, there are times, particularly in the middle months of summer, when Miéville gets bogged down moving us from one central committee meeting to another general membership meeting to another party meeting, with occasional street demonstrations thrown in. It feels at times like he’s forgotten his compelling characters, the importance of capturing the mood of the many, and the physical setting. That said, his final chapter reminded me of John Reed’s classic Ten Days That Shook the World, a book that captures the revolution in rich layers of complexity while giving it an atmospheric treatment that makes the reader feel like they’re participating in the action.

The victory of communism is inevitable, says this 1969 propaganda poster by Konuhov – Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images

For Russians, the final revolution was a kind of “social carnivalesque.” Soldier’s wives, previously beaten and broken, began to “flout laws and intimidate the authorities wherever they possibly could.” “Rural communes began disputing with landlords over rent and rights to the commons. Gangs of peasants” took the firewood they wanted from the estates, used pasture as they saw fit, and decided they would pay “only the prices they reckoned were fair for seed.” Miéville notes that “sense of ‘fairness’ was crucial” and “there were moments of crude class rage and cruelty. But the actions of village communes against landlords were often scrupulously articulated in terms of a moral economy.” Soldiers sent letters to Soviets pleading for books. A group of peasants wrote, “We are sick and tired of living in debt and slavery…We want space and light.”

At the beginning of his book, Miéville argues that the revolutions of 1917 “have long been prisms through which the politics of freedom are viewed.” Many socialists certainly had high expectations at the dawn of the Bolshevik Revolution. Six years after the revolution, with the United States still refusing to recognize the socialist government, the American socialist Eugene Debs explained why in a speech he gave in Harlem. “The reason we do not recognize their Republic is because for the first time in history they have set up a government of the working class; and if that experiment succeeds, good-bye to capitalism throughout the world!” He continued, “We were not too proud to recognize the Tsar…when women were put under the lash…and brutalized and dehumanized…and our President could send congratulations on his birthday to the imperial Tsar of Russia.”

We are in a strangely similar place a hundred years later, with successive US governments praising monarchies and dictatorships as the working class around the world struggles for freedoms gained both in February and in October 1917 in Russia. From Greece to Libya, from Afghanistan to Venezuela, freedom has not come from above. With monarchies ripe to tumble and new worlds to be built we’d do well to remember the crucial lesson from the Russian revolutions. What ended the hated monarchy, and what showed another way to live, came up from below.