Harry Blain

George Orwell’s list of enemies is amongst the longest and most varied in history. A partial list would include pacifists, communists, fascists, capitalists, conservatives, imperialists, vegetarians, teetotalers, Quakers, Catholics, atheists, architects, poets, academics, pamphleteers and people who take their tea with sugar. He died a revolutionary and a socialist that most revolutionaries and socialists had found some reason to hate.

How could someone who was such a nuisance in life become such a saint in death? These days a quote from Orwell usually carries more authority than the Bible, even for people who might have punched the man if they ever spoke to him in one of his much-loved ‘four-ale bars.’ I plead guilty to using the cranky old Englishman in this way, but I do so as someone claiming to have found something in his worldview, which has little to do with the crude and depressing ‘Orwellian’ future presented in 1984. Instead, it is proudly revolutionary, and emerges from the revolutions in culture, politics and language that Orwell himself brought about.

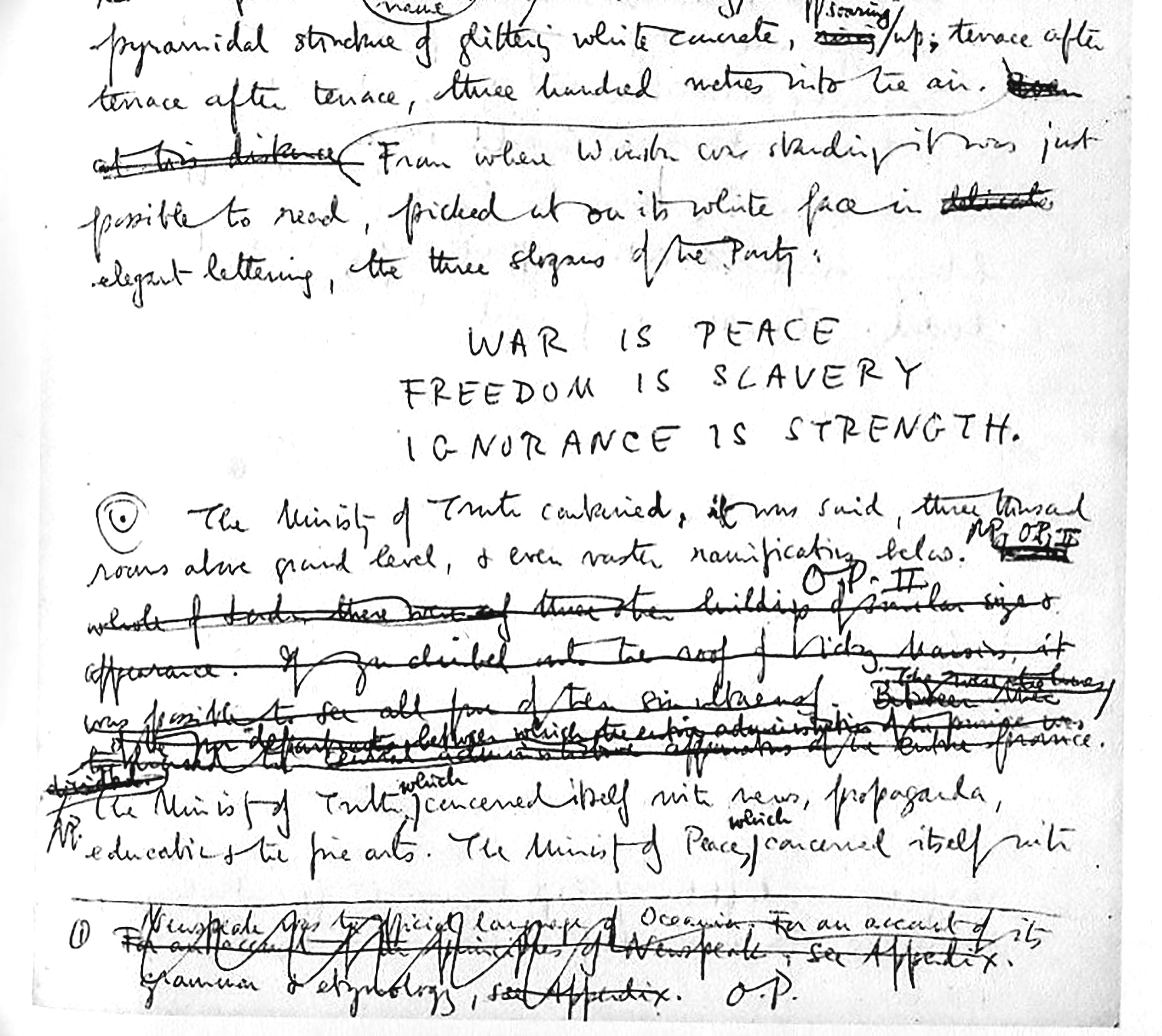

Abandoning “literary ornaments”

Sharp one liners like “all art is propaganda” and “all issues are political issues” are enough on their own to show that Orwell would have thrived in the age of Twitter. He had many flaws, but reticence wasn’t one of them. Verbosity, however, was his biggest gripe, a crime against the English language perpetrated in equal measure by “shock-headed Marxists” and “jingo-imperialists,” who were always “chewing polysyllables” to cloak their real opinions and motives. Orwell set out to dismantle their rhetorical trickery, and do away with what Thomas Paine once called “literary ornaments.” In doing so, he promoted a much wider revolution in how we use language.

Some have called Orwell’s literary style “plain-spoken”, “matter-of-fact” or “conversational.” Although they’re not wrong, they are also missing something. Consider this scene from the (not very successful) novel, Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936), in which he describes the thoughts of the broke protagonist, who has just spent his entire pay-check in one drunken night:

The evil, mutinous mood that comes after drunkenness seemed to have set into a habit. That drunken night had marked a period in his life. It had dragged him downward with strange suddenness. Before, he had fought against the money-code, and yet he had clung to his wretched remnant of decency. But now it was precisely from decency that he wanted to escape. He wanted to go down, deep down, into some world where decency no longer mattered; to cut the strings of his self-respect, to submerge himself—to sink…That was where he wished to be, down in the ghost-kingdom, below ambition. It comforted him somehow to think of the smoke-dim slums of South London sprawling on and on, a huge graceless wilderness where you could lose yourself for ever.

While this is certainly blunt, it can’t be called “matter-of-fact.” It is full of feeling. How does it feel to be just above desperate poverty? What is worse, the material problem of lack of money or the mental torture of maintaining social “decency”? When you fall down one rung of the social ladder, who cares if you fall down another? Down and Out in Paris and London (1933) is a personal chronicle of all these questions; its harshness and brilliance is encapsulated by one of its most intriguing characters. “It is fatal to look hungry”, ‘Boris’ tells Orwell. “It makes people want to kick you.”

Orwell also told us something about how imperialism felt. There was no shortage of anti-imperialist literature on bookshelves in the 1930s (think, for instance, of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness), but Orwell had the privilege of seeing, as he put it in Shooting an Elephant (1936), “the dirty work of Empire at close quarters.” The fruits of this “dirty work,” as a colonial officer in Burma are intimately described: “The wretched prisoners huddling in the stinking cages of the lock-ups, the grey, cowed faces of the long-term convicts, the scarred buttocks of the men who had been flogged with bamboos.”

Orwell also reflected honestly on his own experience. Although “with one part of my mind I thought of the British Raj as an unbreakable tyranny, as something clamped down, in saecula saeculorum, upon the will of prostrate peoples; with another part I thought that the greatest joy in the world would be to drive a bayonet into a Buddhist priest’s guts.” “All I knew,” he concluded, “was that I was stuck between my hatred of the empire I served and my rage against the evil-spirited little beasts who tried to make my job impossible.” Anger and shame, abstract condemnation and raw, personal hatred—this may have been the default mindset of every cop, administrator and pencil-pusher in the British Empire, and, we might add, every United States soldier in Iraq and Afghanistan. Orwell was one of the first to voice it.

“Popular tastes”

Here are some titles of Orwell’s essays and articles: Anti-Semitism in Britain, Shooting an Elephant, The Prevention of Literature, Reflections on Ghandi, Authentic Socialism, How the Poor Die, A Nice Cup of Tea, A Good Word for the Vicar of Bray, Nonsense Poetry, Songs We Used to Sing, Books v Cigarettes, Bad Climates Are Best, British Cookery, Good Bad Books, and – my personal favorite – Some Thoughts on the Common Toad.

Why did this great enemy of totalitarianism, combatant in the Spanish Civil War, and chronicler of 20th Century thought also insist on writing about trivial things? This tendency enraged Orwell’s more sanctimonious left-wing critics. They had a point: they were, after all, living in an era when capitalism seemed to be imploding, fascism was ascendant, communism was fighting for its life – and this guy was writing about the mating habits of toads!

And yet, Orwell had no problem reflecting deeply on things that most of us barely even notice. Smells, habits, and routines mattered. He argued, for instance, that the shelves of small newsagents were “the best available indication of what the mass of the English people really feels and thinks,” whereas movies were “a very unsafe guide to popular taste” and the novel limited, too, as it “aimed almost exclusively at people above the £4-a-week level.” So, he wrote a long essay on the contents of newsagents’ shelves. Similarly, Orwell’s explanation of enduring class boundaries amounted to four words: “the lower classes smell.” This, he said, was the most dominant prejudice of all “bourgeois” Europeans, “the real secret of class distinctions in the West”, because “no feeling of like or dislike is quite so fundamental as a physical feeling.” He then devotes the best part of two chapters to the politics of smells.

Nothing was trivial to Orwell because everything was political. This view is the most basic foundation of what we now call “Cultural Criticism, and the fact that we now seriously study the daily experiences of others owes a great deal to Orwell’s extraordinary eye for the ordinary. Orwell also attempted a less successful revolution in the medium of political and cultural expression. In practice, it was more of a restoration: a case for the pamphlet. The pamphlet, he wrote, is a one-man show. One has complete freedom of expression, including, if one chooses, the freedom to be scurrilous, abusive, and seditious; or, on the other hand, to be more detailed, serious, and “highbrow” than is ever possible in a newspaper or in most kinds of periodicals. At the same time, since the pamphlet is always short and unbound, it can be produced much more quickly than a book, and in principle at any rate, can reach a bigger public. Above all, the pamphlet does not have to follow any prescribed pattern. It can be in prose or in verse, it can consist largely of maps or statistics or quotations, it can take the form of a story, a fable, a letter, an essay, a dialogue, or a piece of “reportage.” All that is required is that it shall be topical, polemical, and short.

This is actually a summary of Orwell’s view by Bernard Bailyn, the leading historian of North American pamphlets between 1750 and 1776. This was the spirit and the time that Orwell was appealing to, and it shaped the style of his essays, which were at once straight-talking, unstructured and often rude. Orwell’s taste for the pamphlet didn’t really catch on, and the great British historian A.J.P. Taylor accused him of nostalgia. Yet both the essay and, now, the blog, have retained some of the pamphlet’s soul. The essays of Christopher Hitchens, for example—on everything from wine and comedy to Thomas Jefferson and the Vietnam War —were tremendously popular, at least until his late-in-life transformation into a neo-conservative mouthpiece. More recently, websites and magazines like the UK-based Open Democracy, and our own Current Affairs and Jacobin, among others, have revived the tradition of medium- to long-form essay writing. At their best, they are funny, thoughtful, acerbic and reflective. Inheritors, in other words, of a style picked up, enlivened and passed on by Orwell.

Reason and emotion

George Orwell, “The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius”, 1941 “Secker and Warburg”. GB, London. (Searchlight Books, No.1). Print-run: 5,000 copies. Contents: Part I: England Your England; Part II: Shopkeepers at War; Part III: The English Revolution.

There is also something more philosophical to Orwell’s revolution in culture, and one of his most interesting insights comes from a 1940 review of Mein Kampf, in which he argued that Hitler had “grasped the falsity of the hedonistic attitude to life”:

Nearly all western thought since the last war, certainly all “progressive” thought, has assumed tacitly that human beings desire nothing beyond ease, security and avoidance of pain. In such a view of life there is no room, for instance, for patriotism and the military virtues. The Socialist who finds his children playing with soldiers is usually upset, but he is never able to think of a substitute for the tin soldiers; tin pacifists somehow won’t do. Hitler, because in his own joyless mind he feels it with exceptional strength, knows that human beings don’t only want comfort, safety, short working-hours, hygiene, birth-control and, in general, common sense; they also, at least intermittently, want struggle and self-sacrifice, not to mention drums, flags and loyalty-parades… “Greatest happiness of the greatest number” is a good slogan, but at this moment “Better an end with horror than a horror without end” is a winner. Now that we are fighting against the man who coined it, we ought not to underrate its emotional appeal.

I recoiled when I first read this. Do human beings really want or need “drums, flags and loyalty-parades”? It certainly would have seemed so in 1940. But even if it was or is true, where does that leave the socialist, whose most basic guiding principle is internationalism? Obviously, Orwell did not think that chauvinistic human instincts should be accepted. He went to Spain to physically fight them. He did, however, see humans as overwhelmingly emotional animals. One of his most consistent problems with “book-trained” socialists was their “machine-worship” and hyper-rationality: a vision of endless, mechanized, conflict-free material abundance. For Orwell, a society without foolishness, vulgarity, toil or prejudice would not be human, and the methods required for building it would have to be close to Stalin’s.

This outlook strongly shaped Orwell’s views on patriotism, an aspect of his thought that remains popular among conservatives on both sides of the Atlantic. He left them plenty of material, admitting that he preferred his upbringing “in an atmosphere tinged with militarism” to that of “the left-wing intellectuals who are so ‘enlightened’ they cannot understand the most ordinary emotions.” Orwell’s fans on the right leave out the part where he argues “patriotism has nothing to do with conservatism.” Instead, “it is a devotion to something that is changing but is felt to be mystically the same,” something you feel and don’t think. Even so, it remains hard to reconcile patriotism with socialism. Orwell’s best attempt can be found in The English Revolution (1941):

England has got to be true to herself. She is not being true to herself while the refugees who have sought our shores are penned up in concentration camps, and company directors work out subtle schemes to dodge their Excess Profits Tax… The heirs of Nelson and of Cromwell are not in the House of Lords. They are in the fields and the streets, in the factories and the armed forces, in the four-ale bar and the suburban back garden; and at present they are still kept under by a generation of ghosts. Compared with the task of bringing the real England to the surface, even the winning of the war, necessary though it is, is secondary. By revolution we become more ourselves, not less. There is no question of stopping short, striking a compromise, salvaging ‘democracy’, standing still. Nothing ever stands still. We must add to our heritage or lose it, we must grow greater or grow less, we must go forward or backward. I believe in England, and I believe that we shall go forward.

This is very good propaganda. Clear, emotive, stirring and, yes, ‘patriotic.’ Would something like it work for us today, modified with some appeal to the traditions of the United States? We won’t know until we try.

Against “timid reformism”

Orwell called for revolution and for socialism: explicitly and repeatedly until the day he died in 1950. Sometimes it is necessary to repeat this, with his legacy now so distorted by people who got no further than a few pages and online summaries of Animal Farm. He hated that the Russian Revolution devolved into Stalinism, but what did he see as the alternative? Not capitalism. “Hitler’s conquest of Europe,” he wrote in Shopkeepers at War (1941), “was a physical debunking of capitalism,” confirming both its inhumanity and ineffectiveness. Liberalism, in the North American sense of the word, didn’t work either. Adjusting a largely rotten system incrementally seemed almost laughable in 1941, and Orwell regularly fumed at the “timid reformism” of the British Labour Party. In ’41, for instance, he wrote that the party “has never been able to achieve any major change,” because “all through the critical years it was directly interested in the prosperity of British capitalism,” devoted as much as anyone else to “the maintenance of the British Empire,” and had turned ‘revolutionary’ politics into a “game of make-believe.”

It might be said that Orwell’s solution was anarchism. You would certainly say so if you’ve read his moving account of anarchist Barcelona in Homage to Catalonia (1938). Noam Chomsky, among others, have referred to Homage in this context. Although they are right to do so from a theoretical standpoint, they could equally refer to Orwell’s practical “Six-Point Programme” presented in The English Revolution:

1. Nationalization of land, mines, railways, banks and major industries.

2. Limitation of incomes, on such a scale that the highest tax-free income in Britain does not exceed the lowest by more than ten to one.

3. Reform of the educational system along democratic lines.

4. Immediate Dominion status for India, with power to secede when the war is over.

5. Formation of an Imperial General Council, in which the coloured peoples [sic] are to be represented.

6. Declaration of formal alliance with China, Abyssinia and all other victims of the Fascist powers.

At the time – remember, Britain was still at war – these proposals were extremely revolutionary, amounting to calls for the end of the Empire, the beginning the end of capitalism, and the complete upending of the British class structure. These were the first steps on the path to Orwell’s “democratic socialism,” which would aspire not just to nationalized industries, but to a classless society.

There’s a lot not to like about George Orwell. He didn’t put much effort into developing female characters in his novels, and made little mention of women in his most noted essays. His attacks on pacifists during the war were often overwrought, more than once insinuating that they were Hitler sympathizers. His obsession with the ‘common man’ can be grating, along with his endless denigration of the ‘intelligentsia.’ Orwell would have rejected any claim to sainthood and so should we. But the least we can do is salvage him from the scrap-heap of cheap quotes and shallow memes, and appreciate him for what he was: a uniquely human revolutionary.