Ashley Marinaccio

Over the past few decades the Palestinian voice has been largely excluded from American cultural circles. While there have been several successful performances of Palestinian narratives on American stages, many Palestinian-made theatre productions that directly address politics and the Israeli occupation have been censored. It was only recently, and after much controversy caused by Public Theatre’s cancellation of its original May 2016 production, that the Jenin-based Freedom Theatre debuted its evocative and emotional production, The Siege, at NYU’s Skirball Center.

Over the past few decades the Palestinian voice has been largely excluded from American cultural circles. While there have been several successful performances of Palestinian narratives on American stages, many Palestinian-made theatre productions that directly address politics and the Israeli occupation have been censored. It was only recently, and after much controversy caused by Public Theatre’s cancellation of its original May 2016 production, that the Jenin-based Freedom Theatre debuted its evocative and emotional production, The Siege, at NYU’s Skirball Center.

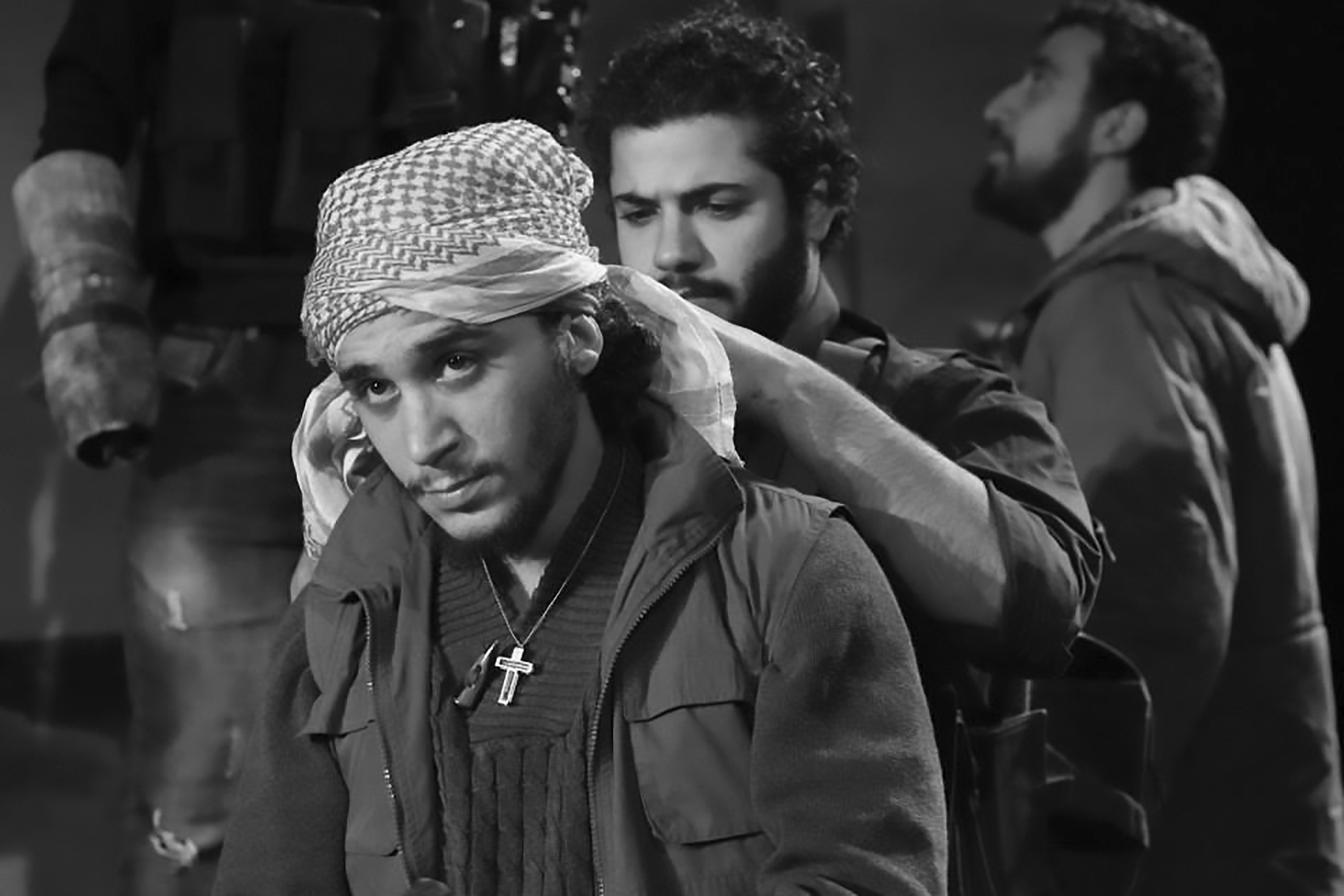

The Freedom Theatre is a cultural center located in the West Bank. Its mission is to “develop a vibrant and creative artistic community that empowers children and young adults to express themselves freely and equally through art while emphasizing professionalism and innovation.” The Freedom Theatre offers workshops and classes in theatre, writing, photography, filmmaking, painting and other creative mediums in addition to theatre performances and a theatre school. Oskar Eustis, Artistic Director of the Public Theater says, “The Freedom Theater of Jenin was founded by Juliano Mer-Khamis as a way of using art rather than violence to create political change. He understood that only be seeing each other as people, looking at seemingly intractable dilemmas from all sides, could change really come to his society.” With a powerful, funny script and well directed performances, The Siege shows audiences just how important it is to see Palestinian bodies unapologetically on stage, telling Palestinian stories. The Siege, created and directed by Nabil Al-Raee and Zoe Lafferty, is based on the 39-day Israeli siege on the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem in 2002. The creative team collected stories of the now exiled fighters from across Gaza and Europe. It is narrated by a tour guide, who transcends time by introducing audiences to the present-day church and its importance to Christians and Muslims across the world, while the main story focuses on the relationships built between six fighters held up in the church by Israeli forces outside. Documentary footage from the events are projected on the walls at various moments throughout the performance to show the events happening “outside” of the church, and provide audiences with context for what the experience looked like in real time. The simple yet elegant set designed by Anna Gisle serves the piece beautifully, evoking the inside of the church, and bringing audiences to the heart of the conflict.

Performed with great integrity, honesty and skill by a company of six actors from across Palestine, The Siege helps us understand the split-second choices and decisions made in the middle of active conflict zones, when your life and the lives of the people you love are consistently in jeopardy. Like all great theatre, this show humanizes a group of people who have been silenced. The directors’ note states, “With The Siege we aim to tell the story behind the western propaganda, upending the dominant narrative of the time: ‘the terrorists have entered a holy place and have taken the priest and nuns hostage.’ It is not the story of victimization but one of resistance in a situation of complete power imbalance.” It is my hope that The Siege is the first of many international tours for this important theatre company, and that this is will allow for more Palestinian voices to be heard in the New York theatre.

I sat down with The Siege’s co-creators Nabil Al-Raee and Zoe Lafferty to speak more about the performance and their experience touring the show to America.

I sat down with The Siege’s co-creators Nabil Al-Raee and Zoe Lafferty to speak more about the performance and their experience touring the show to America.

AM: How long have you been planning to bring The Siege to America? What was that process like?

NABIL: We were struggling to come for more than two years. There were difficulties we had to face. Actors couldn’t get visas. We had to replace one of our actors. The stage manager couldn’t get in and they sent him back, so we had to replace him. Presenting The Siege for American, New York audiences is a big deal. It’s great in so many ways.

AM: What has the American audience reception been? How is it different from the Palestinian reception of the piece back home?

NABIL: It’s important to present it in Palestine, first as a reminder for people to know the story and to know what happened, and especially as we present this story purely as a Palestinian narrative and second because nobody knows about the deal that was made. There was a deal to send these freedom fighters into exile – 26 to Gaza and 13 to Europe. The new generation, especially the generation that was born during and after the second Intifada, didn’t know this story or what happened there. They maybe hear from their families about an invasion or the siege of Bethlehem, but not in detail. But every Palestinian knows what it means to experience a siege. It’s a concept on many levels, in prison, at checkpoints, and on the ground. It’s good, painful and hopeful. It’s painful because it’s a reminder to people of their pain but it’s hopeful because we can take the story and travel with it on the ground.

ZOE: In terms of the UK and America we have the positive responses that are fantastic and enthusiastic and then we have this, let’s see, funny response from people who have not seen the play but somehow know all about it and are really upset about what we’re saying on stage. We have this in Britain as well. We always say, “if you don’t like it, if you are unsure about it, and don’t want to pay money to see it, that’s fine. But come along, we’ll give you a free ticket and you can come for free and see it and we’ll go from there.” But there’s a very aggressive response which has much more to do with censoring it and stopping people from having conversations around this story than it does with actual outrage over what this play is about because obviously people just don’t know.

AM: How was your work received at home?

ZOE: When we first made this play in Palestine my concern is that we were being very critical of the resistance and showing sides of it that were not always positive because, at the end of the day, our job is to put complex human beings on stage and when you do that it’s complicated. Then suddenly we come here and it’s the opposite concern that we’re white-washing these awful people and only showing them as heroes which is absolutely far from the truth. It’s funny, these polar opposite concerns in each country.

AM: What was the devising process like for The Siege?

AM: What was the devising process like for The Siege?

ZOE: The idea personally came when we were doing another play and a guy in the audience stood up and talked about the siege of the church of the Nativity. I went to Ireland initially and met two guys who were part of the siege and they passed on more contact details for others and we spent about a day with each person, interviewing them. Nabil Skyped people in Gaza because nobody can travel there. We also met people in Palestine. There was a blending point where it was every actor and Nabil’s personal story because there is a blending between the reality of your experience, your whole life, and the people you put on stage. We then storyboarded and chose characters and that’s when Nabil turned it into a script.

AM: Are all of your actors from the Freedom Theatre?

NABIL: Some actors came from the Freedom Theatre and others came from different regions in Palestine. Some come from Palestine 48, some from Jerusalem, Nablus, the Jenin refugee camp and the village near Jenin. It’s the same responsibility that theatre has in America or Britain, that you want to bring people from all over together to create something.

AM: Can you tell us a bit more about the Freedom Theatre?

NABIL: The Freedom Theatre proves a safe space for people of different ages to express themselves and share things that they’ve never shared. The training of theatre is a process of buildup, a process of self-discovery, a process of gaining back the trust you’ve lost in so many different ways; it’s a process of stirring up the imagination that in one way or another is frozen under a brutal reality. That training gives hope because if you start to know who you are and what you want then you start to have a responsibility and the freedom about your choices and decisions. This is when you start to relate to the reality around you – the special political and social reality and you can create change.

AM: Do you have any final thoughts you can leave us with?

I think art is hope. Culture is the key for change. I really believe in that. I think it’s important to acknowledge that sharing emotion and anger doesn’t push me to repeat or go through the circle of revenge because that is not the solution – the solution must come in a more creative way.

For more information on The Freedom Theatre:

Website:

www.thefreedomtheatre.org

Facebook:

www.facebook.com/thefreedomtheatre

Twitter: @Freedom_Theatre

Instagram: thefreedomtheatre