Bhargav Rani

Poster in defence of Kabir Kala Manch – source: https://kabirkalamanch.wordpress.com/2013/06/28/sheetal-sathe-of-kabir-kala-manch-granted-bail-at-last-freekabirkalmanch/

On the morning of 2 April 2013, two prominent members of the Pune-based cultural group Kabir Kala Manch, Sheetal Sathe and her husband Sachin Mali, gathered outside the premises of the Maharashtra Legislative Assembly in Mumbai. This was their first public appearance in two years, having been compelled to go underground after an arrest warrant was issued in their names by the Maharashtra state government. Sathe and Mali assembled in front of a modest crowd of supporters, sang a few songs, and issued a statement unequivocally asserting that this was not a surrender but a satyagraha, a staunch insistence on truth, a demand for justice. Their decision to come out of hiding, they said, was motivated simultaneously by their faith in the due process of the law as well as their desire to put the very democratic character of the state and its dictum of freedom of expression to test. Within moments, officers from the Maharashtra Anti-Terrorist Squad arrived on the scene, and took Sathe and Mali into custody. Over the years, the Indian state has repeatedly failed to stand up to their test.

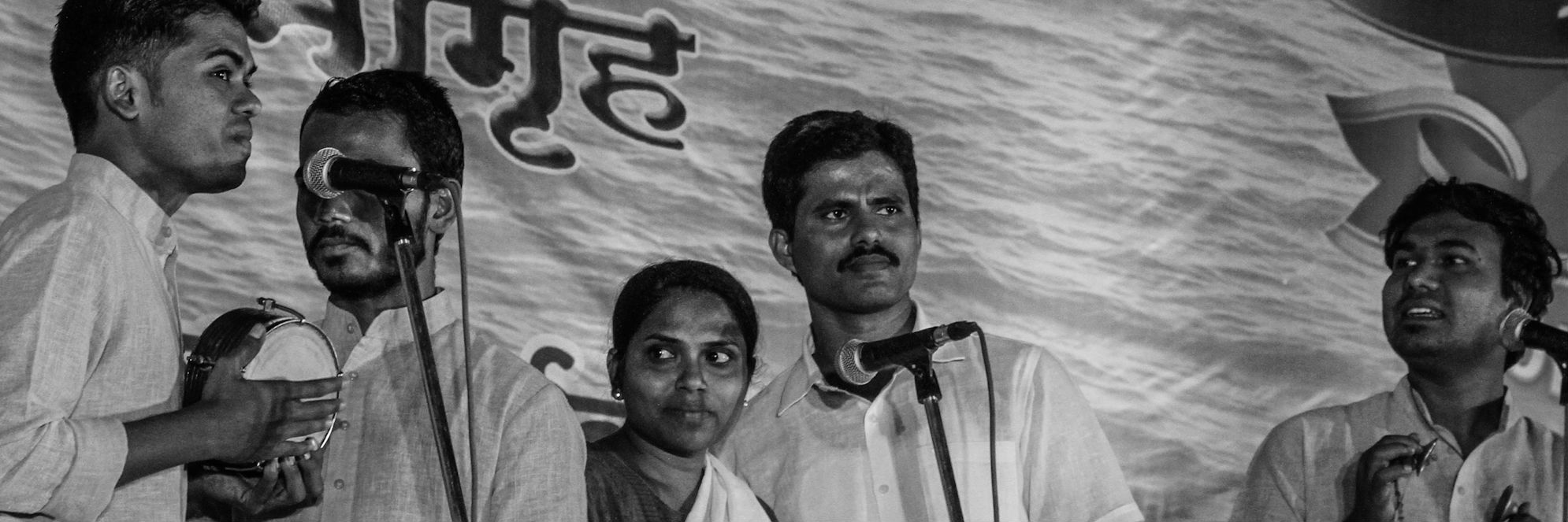

That article is about the questionable construction of the terrorist figure by the state. Sathe and Mali are not terrorists in any common understanding of the word. Kabir Kala Manch is a political-cultural group that employs performance as a means of protest against the state. Through their repertoire of songs, plays and poetry, they confront the entrenched structures of oppression that proliferate within Indian society. More specifically, they are a predominantly Dalit group, performing at various bastis, or slums, in working-class neighborhoods in Pune, where they stage street plays and sing songs of resistance advocating caste emancipation, women empowerment, and minority rights. Their performances also frequently criticize land acquisition policies, the failures of democracy, and the systemic discrimination of a capitalist state. Sathe and Mali are essentially artists – singers and poets – and who use the medium of performance to reach out to the marginalized and to puncture the complacent apathy of the Brahminical ruling classes.

Poster in defence of Kabir Kala Manch – source: https://kabirkalamanch.wordpress.com/2013/06/28/sheetal-sathe-of-kabir-kala-manch-granted-bail-at-last-freekabirkalmanch/

Such persecution of artists as “terrorists” by the state through the invocation of a draconian law underscores the dubious nature of the state’s discursive manipulations. At the most elementary level, it begs some questions. Who is a “terrorist”? What parameters determine the qualification of an individual as a “terrorist”? Who are the terrorized? What are the means employed by the so-called “terrorist” in order to terrorize; to perpetrate “terrorism”? The answers that the case of Kabir Kala Manch offers to these basic questions are each incrementally more outlandish than the other. Moreover, the persecution of artists by the Indian state, the largest democracy in the world, strikes at the very foundational principles of democracy, provoking a critical appraisal of the nature of democracy itself.

Kabir Kala Manch was first started in 2002 in the wake of the Gujarat Riots. After a train carrying Hindu pilgrims from the disputed Babri Masjid site at Ayodhya was mysteriously burnt down on 27 February 2002, at a railway station in Godhra, killing fifty-nine passengers, Muslims in Gujarat as a whole were painted as responsible by right-wing factions and Hindu mobs, and it lead to one of the most gruesome pogroms of torture, rape, and murder against them. By 4 March, when the riots were finally brought under control, over 2,000 Muslims had been killed and over a hundred thousand displaced from their homes, many of them still awaiting justice in ghettoized transit camps in Ahmedabad. While the political climate that prevailed in the country over the next decade governed the tenor of discourses that now constitute the “official” history of the Gujarat riots, there also runs a substantial counter-discourse that implicates the highest offices of the state, including the then-Chief Minister of Gujarat and the current Prime Minister Narendra Modi, as complicit in the orchestration of these riots for electoral advantage.

In the aftermath of the riots, the state’s pretensions to imparting justice to the victims was a mockery. More than half the people arrested were taken in from predominantly Dalit areas, and a third more from Dalit-Muslim areas. Less than a hundred (of the nearly 3000 people arrested) were taken from areas in which the most Muslims were murdered. While the number of Hindus arrested exceeded, if only marginally, the number of Muslims, only 32 of those arrests were of upper-caste Hindus. Thus, in a meticulously orchestrated decimation of an entire community of Muslims through a collusion of political leaders and Hindu right-wing factions, caste was as much a factor as religion and Dalits were rounded up as the sacrificial lambs in a travesty of justice.

It was in response to this somber state of affairs that Kabir Kala Manch was started by Amarnath Chandaliya, along with other Pune-based activists, as a means of cultural expression of resistance and a performance of protest. The two central concerns underpinning the activism of the group is that of caste and class, a politics seeped equally in Ambedkarism and Marxism. Even as the group foregrounds the politics of caste oppression through its cultural activism, it never loses sight of their class struggles and explicitly attacks the complicity of the capitalist state in the perpetuation of caste hierarchies. For Kabir Kala Manch, caste emancipation is not a possibility within the capitalist structures of oppression that stand antithetical to any idea of affirmative action, and the two are entwined in a figuration of mutuality must be confronted and dismantled in the same vein.

In 2005, Sheetal Sathe, a talented singer, poet and musician, a graduate of Fergusson College, Pune, and a Dalit activist, joined Kabir Kala Manch along with her husband Sachin Mali, her cousin Sagar Gorkhe, and Deepak Dengle and Siddharth Bhosle. Sathe, Mali and the others came in contact with a number of radical left activists in the group, including some members of the banned Communist Party of India (Maoist), who were influential on their activist agenda. Then, in 2006, the Khairlanji massacre happened. In a small village in Maharashtra, four members of the Bhotmange family, belonging to a Dalit caste, were brutally lynched over a land dispute, and the women paraded naked in public and gang-raped before being murdered in cold blood. The national media and the political leaders alike ignored this massacre until the Dalit outrage spilled onto the streets of Mumbai in the form of vehement demonstrations against the state. It was during these mass protests that Kabir Kala Manch came to the public’s attention, as they assembled on the streets every day and sang protest songs and staged street plays about caste emancipation. While the political classes have sought to erase the memory of the massacre from the national consciousness, Kabir Kala Manch has ensured its persistence by commemorating the dead in and through their poetry.

In 2011, the Government of India, under the provisions of the draconian Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act of 1967, a law inscribed in a legal language that is dubious at best, declared Kabir Kala Manch a threat to national security and incriminated a number of its activists as Naxalites or Maoists actively engaged in logistical support to insurgent movements in the nation-state. While Kabir Kala Manch activists have been vocal in their support of the rights of farmers and tribes claiming ownership of the land they work on as well as the militant means of resistance that a number of these groups have espoused, there is no evidence that they had ever taken up arms against the state. The primary mode of protest for Kabir Kala Manch has always been cultural, with its activists staging street plays and singing revolutionary songs against the land acquisition policies of the government—policies that lie at the root of many insurgent movements.

We thus have a state that, through a manipulative application of an insidious law, finds the rationale to persecute and prosecute cultural activists, not for any violent infringement of its democratic principles but for simply raising a voice of dissent. In 2011, immediately after the state invoked this law against Kabir Kala Manch, it authorized a crackdown on musicians and activists by the Anti-Terrorist Squad, and Dengle and Bhosle were put to jail. Dengle, in an interview, recalled his time in jail,

“Once I was in custody, they started beating me; they hit me with their belts. They were asking me where Sachin and Sheetal were. I didn’t know, so they continued to hit me. They stripped me, tied my hands and legs with a rope and hung me from the ceiling. Then they took this oil called Suryaprakash oil, and put it all over my body, including my groin. It causes burning all over and makes it hard to breathe. I was in so much pain that I asked them to shoot me and get it over with. They only untied me once I lost consciousness.”

Sathe and Mali, along with two others, Sagar Gorkhe and Ramesh Gaichor, were forced to go into hiding for two years. In 2013, they finally reemerged and gave themselves up to the state, after Dengle and Bhosle were released on bail with the judge declaring that being sympathetic to the Maoist cause was not a crime, although pleading innocent on all charges. Sathe, who was pregnant at that time, Mali, Gorkhe and Gaichor were immediately imprisoned and were rejected bail twice by the judicial system. Sathe was granted bail in late 2013 on humanitarian grounds, when she was almost eight-and-a-half months into her pregnancy, while the other three languished in jail for four more years, till they were finally released in 2017. While Sathe and Mali have split from the group due to ideological differences to start a new cultural front, Navyan, Kabir Kala Manch has over a dozen committed artists who rehearse at least thrice a week and continue to perform regularly in Pune slums.

The law that facilitates such persecution of artists by the state demands some scrutiny. Rustom Bharucha, in his book Terror and Performance, highlights the slippery terrain that the language of terrorism inhabits, and in what he calls the “doublespeak of ‘terrorism,’” asserts that, “Even as there is no consensus on the official definitions of terrorism, we have no other option but to engage with them not least because they could be the most powerful legitimizing devices for the perpetration of terror in our times. The absence or the lack of consensus around adequate official definitions does not stop them from being used in insidious ways.” As a closer inspection of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act of 1967 reveals, the ambiguity of the language in the law is not incidental to its articulation. It is rather a conscious, calculated ruse that the state employs to preserve of the status quo.

The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, first instituted in 1967, is a law that pertains to the powers bestowed on the Indian state in dealing with activities that threaten its integrity and sovereignty. While essentially arcane, as the date on the Act indicates, it has undergone few minor amendments over the years, the most recent of which was in 2008, impelled by the terrorist attacks in Mumbai. Reincorporating certain provisions from the Prevention of Terrorism Act of 2002, which was discredited and repealed in 2004 due to its rampant misuse by the police, the amended act invested the state with unbridled powers to not only curb insurgency threats on the basis of mere suspicion but to even suppress any form of dissent. Much like Bush’s “war on terror” in the wake of “September 11,” the Indian government capitalized on the palpable sense of terror that pervaded the public consciousness after the terrorist attacks in Mumbai in November 2008, and passed the amendment granting itself almost autocratic powers with little debate in the parliament. The 2008 amendment stipulates a terrorist act as one involving the use of “bombs, dynamite…other explosive substances or inflammable substances or firearms or other lethal weapons or poisonous or noxious gases or other chemicals or by any other substances…of a hazardous nature or by any other means of whatever nature.”

While the law was ostensibly passed as an anti-terrorism law, stipulating a range of actions that could justifiably be argued to constitute terrorism, the seemingly careless and yet calculated inclusion of the final clause — “by any other means of whatever nature” — underscores the state’s crafty manipulation of the legal language. Who, according to the state, is a terrorist? Practically anybody! In addition, the law also stipulates that any act “likely to threaten the unity, integrity, security or sovereignty of India” can be construed as a terrorist act, thus introducing a very problematic subjectivity into its implementation even as it jeopardizes the core democratic mandate of the presumption of innocence until proven guilty.

It is imperative to remember Bharucha’s crucial emphasis on the “language of war,” for this language, as he argues, is imbued with a “performative energy, whereby words are not just descriptions but the embodiments of actions.” It can be argued that the law does not merely function with performative force, but rather performativity is its axiomatic premise. That is, its performativity is an a priori condition for the law, and the stakes involved in the articulation of a law are so high precisely because the words necessarily shape the socio-political realities that define the lives of its citizens in palpable ways. A phrase misplaced can transform an “artist” into a “militant” into an “insurgent” into a “terrorist,” and completely overhaul the material realities of his or her daily life. The manipulation of legal language by the state must thus be understood as a conscious, concerted effort towards inflecting the performativity of the law. In Bharucha’s words, “Language is not just ‘speaking’; it is ‘doing’, ‘torturing’, ‘killing’.”

Kabir Kala Manch’s incrimination as terrorists is an application of that sly appendage of infinite significations, that phrase “by any other means of whatever nature,” in the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. The specific signification to which it is tethered in this context here is the group’s mode of protest, their songs and their theatre, which are identified by the state as their “weapons.” The obvious dichotomy that emerges is violence as opposed to non-violence, and one can argue that it is the essentially non-violent character of Kabir Kala Manch’s modes of resistance must absolve them of all charges. However, while this is undeniably true, we must be cautious to not let our activist zeal to exculpate this group of artists prevent us from an attention of the nuances of the argument. At the outset, it must be conceded that any cultural or political group that chooses to employ performance as a means of protest does indeed strategically espouse it as a weapon against the oppressive structures of the state. We must heed Bharucha’s insistence that we stop thinking of theatre as inherently “non-violent” and consider the “violence of non-violence.” To recall the Brazilian activist Herbert de Souza’s fiery retort to Bharucha’s provocative question of whether we no longer need to fight, “Of course we have to fight…Think of Gandhi. What could be more violent than non-violence?”

But where exactly does the violence of non-violence lie? Bharucha sums this up when he says, “the ‘violence’ of non-violence cannot involve killing or even abusing the other; rather, it necessitates the courage of standing up to the other, receiving the blow, and being prepared to die not for some ideal of heroism or transcendent ideal but for the affirmation of Truth.” He then goes on to engage with the visceral, corporeal register of this proposition to analyze the extreme forms of disciplining of the body and penance that Gandhi advocated and practiced as well as the practices of self-mutilation as resistance, like lip-sewing and blood-graffiti, undertaken by prisoners in detention camps in Australia. While it is important to never lose sight of this corporeal essence of violence, violence/non-violence must also be unhinged from its inordinate dependence on the affective quality of blood in all its visceral presence, in order to definitively implicate violence that permeates our daily life in all its banality. Violence manifests in the seeming non-violence of everyday experiences of caste discrimination, in the politics of touch and purity, just as it persists in the non-violence of performed dissent. The former must be understood as non-violent violence, while the latter as violent non-violence. The members of Kabir Kala Manch, in and by virtue of their “courage” to stand up, to “receive blows,” and in their preparedness “to die” for the cause of Dalit rights, for the “affirmation of Truth,” have already put their corporeality in peril’s way. Their acts of dissent have already “marked” them in the invisible crosshairs of the state. And violence does not begin with the pulling of the trigger, it is always already present in the “marking” itself.

While Bharucha provides much of the critical vocabulary for an investigation of the violence of non-violence embodied by the artists of Kabir Kala Manch, his propositions on the violence of non-violence stem from a lineage that has its roots in Gandhi, and it would be erroneous to implicate the violent non-violence of Kabir Kala Manch in this lineage. What I want to emphasize here is that Gandhi exerts an almost hegemonic influence over both the discourse and praxis of non-violence in today’s world. This is not so much to question the validity of this persistent influence of Gandhian thought in thinking through non-violence, but to recognize other agents and players in the deployment of non-violence as a strategy of resistance against the state. The violent non-violence of Kabir Kala Manch traces its genealogy not to ahimsa, Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violence, but to the figure of Ambedkar, himself an embodiment of the paradox of the violence of non-violence. I would like to end this article by offering two examples of the revolutionary violence that lies underlies Ambedkar’s philosophy, one at the level of discourse and the other at the level of praxis.

At a discursive level, Ambedkar’s 1936 published speech, Annihilation of Caste, is arguable one of the most violent pieces of writing that has emerged from India. It is, as Arundhati Roy puts it, a “breach of peace.” A scathing indictment of the caste system, it was originally written for a speech that Ambedkar was invited to deliver at the annual conference of the Jat-Pat Todak Mandal in Lahore, a radical faction of the Hindu reformist organization, the Arya Samaj. But the profound radicalism of his propositions, which the organizers found “unbearable,” led to the cancellation of the conference. Ambedkar then decided to publish his speech as well as his correspondence with the organizers to provide his readers with the context for the cancellation of the conference.

In his speech Ambedkar unpacks the manifold discourses and practices that inform the perpetuation of caste in Indian society, analyzes the arguments and counter-arguments for caste emancipation, and eventually calls for a radical renunciation of Hinduism itself, attacking its very foundations, its sacred scriptures and religious texts. To quote just one brilliant passage:

“It is no use seeking refuge in quibbles. It is no use telling people that the shashtras do not say what they are believed to say, if they are grammatically read or logically interpreted. What matters is how the shastras have been understood by the people. You must take the stand that Buddha took. You must take the stand that Guru Nanak took. You must not only discard the shastras, you must deny their authority, as did Buddha and Nanak. You must have courage to tell the Hindus that what is wrong with them is their religion – the religion which has produced in them this notion of the sacredness of caste. Will you show that courage?”

Unlike the reformist agendas of the Jat-Pat Todak Mandal and many other Hindu caste emancipation organizations of that time, Ambedkar called for a complete revolution. He staunchly believed that the root of the evil of caste oppression lay in the essence of Hinduism itself, and rejected all claims of the possibility of an emancipatory project within its auspices. Ambedkar recognized that any ideology of oppression and its concomitant structures must be premised on a tacit compliance, albeit forced, of the oppressed, who in turn legitimize these structures and thus participate in its perpetuation. Acutely conscious of the Brahminical gun pointed to his head in its demand that he perform his assigned part and make the prescribed moves, Ambedkar indignantly flings the board away, violently scatters all the pieces, and adamantly refuses to play by their rules. Against the overarching violence of the Hindu state that threatens any challenge to its status quo with death, Ambedkar’s “courage” stands out in his affirmation of truth, and that is where the violence of his non-violence lies.

This violent non-violence of Ambedkar that evinced in his discourses also translated into his praxis for resistance. He had famously declared in 1935 that though he was born a Hindu, he would ensure that he didn’t die a Hindu, and he stuck to his word. Days before his death, Ambedkar converted to Buddhism—having studied it all his life—in a public ceremony in Nagpur, Maharashtra. The inherent violence of his non-violent act of radical renunciation notwithstanding, the sheer scale of the violence must be understood in light of the fact that half a million of his supporters also converted to Buddhism on that day. These ceremonial mass conversions persisted after his death on 6 December, 1956, such that by 1959, between fifteen and twenty million Dalits had renounced the religion that had persistently treated them as less than humans. The threat of these conversions to the integrity of the Hindu state should not be understated, and the question of conversion still holds valence in the current political climate, with the issue of gharwapsi, or “homecoming,” the Hindutva’s response of re-conversion back to Hinduism, being a case in point. Thus, the violence of non-violence that we identify in Kabir Kala Manch’s cultural performances is a legacy of this radical figure of Ambedkar, whose very invocation in a caste-ridden, Hindu dominated society is charged with the specter of violence. The appropriation of Ambedkar by right-wing, Hindu factions in their pandering to lower-caste electorates in contemporary politics must be understood as their attempt to tame Ambedkar, to sanitize him, to render his explosive ghost benign.

As a final note, it must be noted that the persecution of Kabir Kala Manch artists as “terrorists” by the state is a violation of the “right to perform.” This question had come to the foreground in 1989, in light of the brutal murder of Safdar Hashmi, the theatre director of another political-cultural group, Jana Natya Manch. Without being too rhapsodic about theatre’s liminality, it must be conceded that the manifestation of the tensions fraught in the question of the right to perform in contemporary political discourses underscores the persistence of theatre’s relevance as a modality of resistance. Bharucha locates the political valence of theatre in its affirmation of freedom; as he asserts, “There can be no compromise on the demand for this freedom – it is not a freedom-in-waiting, but a freedom which is embodied and lived every single time in the here and now of performance practice.” Against the realities of caste oppression that essentially serve to limit the freedoms that Dalits can enjoy, the radical affirmation of the right to perform, the freedom to perform, resonates with the call for Dalit freedom and justice. The fight for Kabir Kala Manch activists who have been maliciously incriminated by the state is a fight for artists, it is fight for caste emancipation, for the right to perform, and in the final instance, it is a fight for freedom.

Pingback: India- Have your heard of our very own Bob Dylan – Gaddar ? | Kractivism