Leah Light

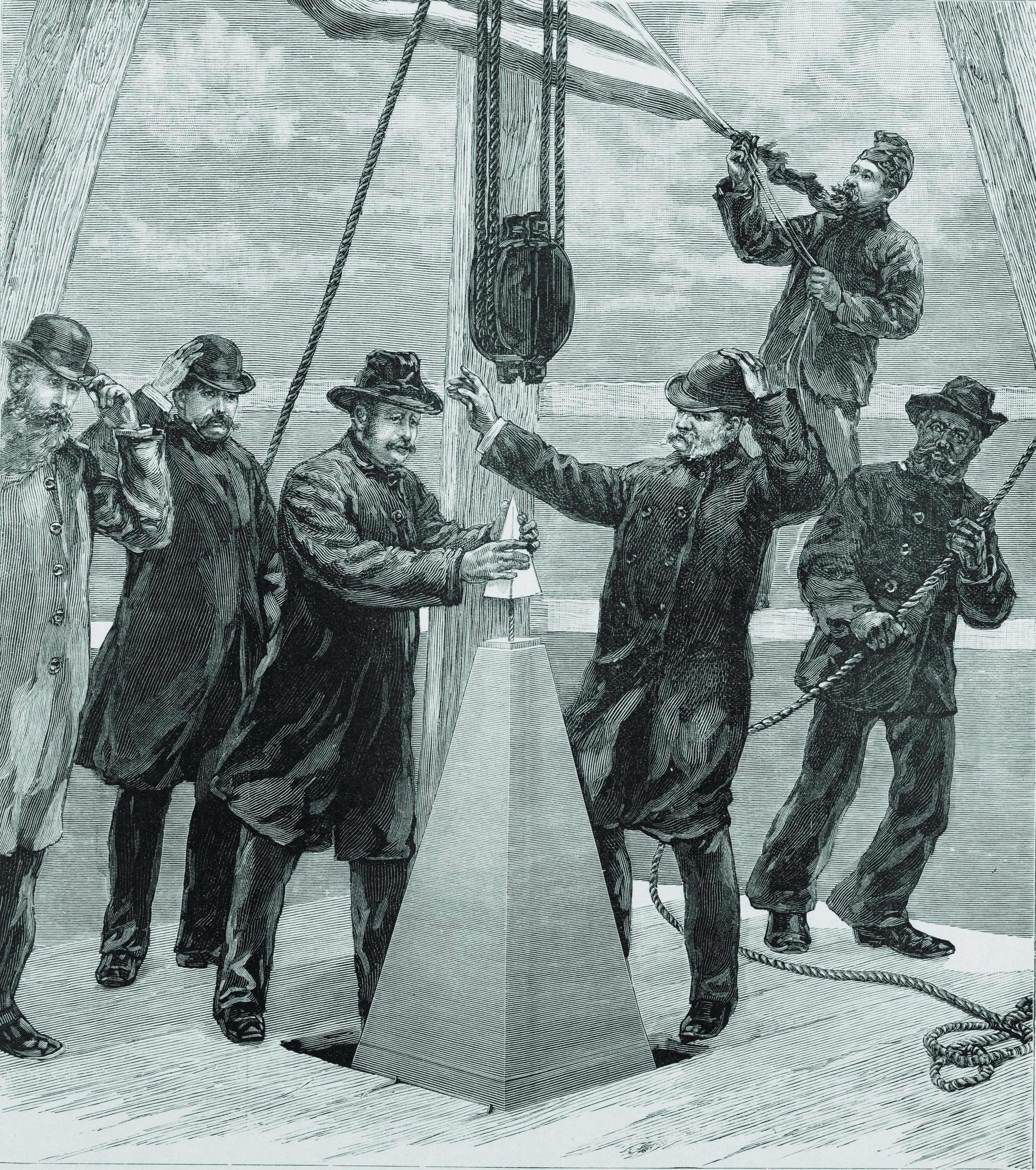

About a month ago, I was asked to do some research on capstone courses for undergraduates at CUNY. Frankly, I’d heard the term before but barely knew what it meant. It’s a beautiful word, “capstone,” literally signifying a large, flat stone that mounts and bolsters a wall, or bridges two pillars over a tomb, or the top triangular stone on a pyramid. It entails hardness, specificity, completion – a crowning achievement. In the academic context, which is now the more common usage, a “capstone” is usually a project that occurs at the end of an academic program, makes coherent the overarching trajectory of study, and brings together different skill sets, methodologies and content areas with an exploration of their possible applications. A capstone is supposed to be interdisciplinary, student-driven, integrative, and may or may not differ significantly from a senior thesis or senior seminar, depending on who you’re talking to. The feasibility and utility of such a project is much debated, I found, after asking anyone I could about capstone courses and other “exit-point” experiences for undergraduates at CUNY.

About a month ago, I was asked to do some research on capstone courses for undergraduates at CUNY. Frankly, I’d heard the term before but barely knew what it meant. It’s a beautiful word, “capstone,” literally signifying a large, flat stone that mounts and bolsters a wall, or bridges two pillars over a tomb, or the top triangular stone on a pyramid. It entails hardness, specificity, completion – a crowning achievement. In the academic context, which is now the more common usage, a “capstone” is usually a project that occurs at the end of an academic program, makes coherent the overarching trajectory of study, and brings together different skill sets, methodologies and content areas with an exploration of their possible applications. A capstone is supposed to be interdisciplinary, student-driven, integrative, and may or may not differ significantly from a senior thesis or senior seminar, depending on who you’re talking to. The feasibility and utility of such a project is much debated, I found, after asking anyone I could about capstone courses and other “exit-point” experiences for undergraduates at CUNY.

Let me clarify first that it’s difficult to talk about capstones without limiting the conversation to a particular discipline or set of related disciplines. This is somewhat counterintuitive because capstones are supposed to be integrative, often encouraging “real-world” or professional applications of skills that show an ability to apply materials and methods from one field to another and to demonstrate critical abilities that connect different disciplines. Capstone projects (or required senior seminars, or capstone courses) are rarely required for most majors in an undergraduate program at CUNY. They are more common in the applied sciences and pre-professional programs than in the social sciences and humanities, although there are some notable exceptions. They are frequently required in the honors colleges, and alternately, some departments offer them as part of departmental honors. Departmental honors (which vary with department) can often replace a capstone requirement for a particular honors college or program, and these programs may entail a research project, paper, or an honors course. Speaking with Lev Sviridov of the Macaulay Honors College at Hunter, I mentioned that I was having difficulty discerning what did and didn’t qualify as a capstone experience. “Welcome to the story of my life,” he laughed.

The Macaulay Honors College, a CUNY honors program for students in different CUNY schools, has a capstone project required for all students in their senior year, but this project can be replaced by departmental honors work of equivalent scope. Their capstone, called the “Springboard” project, is intended to be integrative, and also aims to provide its students with some “real-world” experience. Its website details this project as work that “builds on a student’s earlier work and displays and reflects that work,” “proposes new directions, asks unanswered questions, poses unresolved dilemmas…proposes specific research and learning pathways, providing a plan with clear goals and defined next steps,” and “is presented to, and open to the interaction of, a wide public audience.”

The Macaulay Honors College, a CUNY honors program for students in different CUNY schools, has a capstone project required for all students in their senior year, but this project can be replaced by departmental honors work of equivalent scope. Their capstone, called the “Springboard” project, is intended to be integrative, and also aims to provide its students with some “real-world” experience. Its website details this project as work that “builds on a student’s earlier work and displays and reflects that work,” “proposes new directions, asks unanswered questions, poses unresolved dilemmas…proposes specific research and learning pathways, providing a plan with clear goals and defined next steps,” and “is presented to, and open to the interaction of, a wide public audience.”

The Springboard project aims to be “a multidirectional communication” –that “faces outward,” and focuses on process rather than product. However, if students take an honors seminar or otherwise achieve departmental honors, the requirement is waived. The Verrazano School, an honors school located at the College of Staten Island, also requires a capstone for all majors. According to the handbook, their project entails: “work[ing] closely with a professor to create a scholarly or otherwise significant project that builds on their knowledge and interest in a field, or fields, of study.” It acknowledges that “every field is different, so there is not a singular definition for the Capstone… The departmental thesis/project associated with honors in the major will fulfill the Verrazano capstone project requirement; Verrazano students who are eligible to complete honors in the major are strongly encouraged to do so.”

To find out more, I spoke with Cheryl Craddock, the Associate Director of the Verrazano School. She feels that a capstone, like Verrazano’s, should be “student-driven, involving substantive interaction with faculty,” and one that “brings together various critical methodologies.” I asked her if there was a distinctive difference between a senior thesis project and a capstone, and she replied that yes, there was, but in the undergraduate case at CUNY, the difference is not substantial as long as the above criteria were sufficiently met.

To find out more, I spoke with Cheryl Craddock, the Associate Director of the Verrazano School. She feels that a capstone, like Verrazano’s, should be “student-driven, involving substantive interaction with faculty,” and one that “brings together various critical methodologies.” I asked her if there was a distinctive difference between a senior thesis project and a capstone, and she replied that yes, there was, but in the undergraduate case at CUNY, the difference is not substantial as long as the above criteria were sufficiently met.

Professor Craddock’s emphasis on “substantive interaction with faculty,” of course, made me raise an eyebrow. In my discussion with Sarah Chinn, Chair of the English Department at Hunter College, she remarked that with over 900 students in the major it would be nearly impossible for each student to do an independent project under close faculty supervision. Nonetheless, she is thinking about implementing a kind of capstone, or required senior seminar course for Hunter’s English majors. What she envisions is not exactly an individualized project, but a required 400 level course for all majors, a “culminating experience, with a significant research component and a final senior thesis.”

It would be an opportunity for students to reflect on their entire course of study, and to see the ways in which various acquired skills (close reading, research, theory) can come together towards comprehensive work, giving students a sense of what graduate work in literature is like. Also, importantly, it would provide a way for university-wide assessments to look at the majors and draw meaningful conclusions about what English students are actually learning, and how that learning is being applied.

Hunter’s history department has HIST 300 or 400, “Historical Research,” a required exit-point course for all majors which involves “supervised individualized student work under faculty direction in planning, preparing, and polishing a history research paper,” but when pressed, a representative preferred to call it “keystone,” or merely a research course. There are capstones offered in the humanities at Baruch, including one in philosophy, there is a senior seminar in English at Lehman, and there is a capstone for Linguistics at Brooklyn College. Capstones are more prevalent in business, urban affairs and political science, and are common in computer science.

The computer science major at Hunter seems to be the only one that mandates a capstone requirement for all students. One of the challenges faced there, according to Eric Schweitzer, is keeping the capstone “fresh,” because the department wants to produce employable computer science majors who will be competitive for relevant jobs. The curriculum then is accountable as much to opinions in academia as to markets and trends in commerce and IT. Schweitzer noted that in the early to mid-2000s, when smartphones were still burgeoning into the mainstream (with products like Treo, Sidekicks, Blackberry and iPhone in 2007), computer science undergraduates frequently reported gainful employment directly resulting from work showcased in their capstone projects.

Those days, says Schweitzer, are pretty much gone. The computer science capstone, also, isn’t strictly cumulative as the professors stipulate certain requirements in each instance that may exclude or limit the way a student can use certain areas of study that were previously important to her. For example, the capstone may require work on a backend project while a student may have previously focused on technology for smartphones. Another variable that is introduced in this capstone is the group dynamic, as all the projects in CSCI 400 are collaborative. The course intends to acclimate students to working with others – developing interactive programs while collaborating with other IT professionals and laypeople, an awkward but necessary component of “real-world” computing. Because of the various (and specific) criteria laid out by professors (which change depending on who’s teaching it), students are not always able to do the project that they had anticipated, despite the assumption that they should begin conceiving the project (before forming their group) during their junior year. The single-semester, contained nature of the project also limits the way in which computer science’s capstone can be called truly cumulative or integrative.

I also asked Professor Schweitzer about the relationship between capstones and assessment. Capstone projects, senior seminars, and other exit-point courses are often implemented in part (if not in whole) for assessment purposes. University administrators (and the Middle States Commission on Higher Education, the organization that manages accreditation for the US Secretary of Education in New York and several other states) want to know what students are actually learning in their majors, and they want proof. Schweitzer expressed frustration on two related points. First, he noted that the capstone project is expected to be consistent with departmental learning outcomes. The department’s intended learning outcomes should be consistent with those of the college (and because of initiatives like Pathways, to some extent with CUNY’s as well) and yet, to his knowledge, no such university-wide learning outcomes have been published. He argued then that it’s hard to engineer a curriculum, or a capstone, to meet a set of expectations that have not been clearly delineated, and that students, professors and department-level administrators are in some sense struggling to adhere to standards and protocols that are unclear if not outright unavailable. He also mentioned that “student success” is typically measured by student retention and graduation rates. “It’s trivial,” he said, “to achieve close to 100 percent retention and graduation rates by only collecting tuition and giving out ‘A’s…that’s not success, that’s not teaching. But that’s what the administration is looking for when they’re looking for ‘student success.’” He mentioned that he’d like to perform an assessment of assessment – do a study that assesses to see whether students under assessed curricula came out better educated, adjusted and prepared for employment.

I also asked Professor Schweitzer about the relationship between capstones and assessment. Capstone projects, senior seminars, and other exit-point courses are often implemented in part (if not in whole) for assessment purposes. University administrators (and the Middle States Commission on Higher Education, the organization that manages accreditation for the US Secretary of Education in New York and several other states) want to know what students are actually learning in their majors, and they want proof. Schweitzer expressed frustration on two related points. First, he noted that the capstone project is expected to be consistent with departmental learning outcomes. The department’s intended learning outcomes should be consistent with those of the college (and because of initiatives like Pathways, to some extent with CUNY’s as well) and yet, to his knowledge, no such university-wide learning outcomes have been published. He argued then that it’s hard to engineer a curriculum, or a capstone, to meet a set of expectations that have not been clearly delineated, and that students, professors and department-level administrators are in some sense struggling to adhere to standards and protocols that are unclear if not outright unavailable. He also mentioned that “student success” is typically measured by student retention and graduation rates. “It’s trivial,” he said, “to achieve close to 100 percent retention and graduation rates by only collecting tuition and giving out ‘A’s…that’s not success, that’s not teaching. But that’s what the administration is looking for when they’re looking for ‘student success.’” He mentioned that he’d like to perform an assessment of assessment – do a study that assesses to see whether students under assessed curricula came out better educated, adjusted and prepared for employment.

Despite its limitations, the capstone, he felt, often succeeds in doing what it purports to: that is, simulating “real-world” work experience, motivating student initiative and creativity, integrating different skills and methods, and giving students an opportunity to reflect on their overall course of study in relation to their professional aspirations. Professor Stan Altman of the School of Public Affairs at Baruch expressed other concerns about undergraduate capstones. The undergraduate major in public affairs is based in what was originally a master’s program, and this is in part why it retains a capstone. Public affairs is, by nature, integrative: it includes engineering, political science, economics, communications, etc., and all the different faculty in public affairs are continually in touch with one another about their curricula and students. Nonetheless, Altman feels that senior capstone courses or projects (in their case PAF 4401) do not sufficiently inculcate in the students those critical abilities that such demand; or at least, they unfairly put the onus on the student, rather than the faculty and overall curriculum, to show abilities at the end of her undergraduate career that she should have been developing consistently and continually, with ongoing supervision, from her sophomore year.

Altman also invoked Bernard Baruch, the economic advisor to Presidents Woodrow Wilson and Franklin D. Roosevelt and a graduate of City College in 1889, who had claimed that his most rewarding course in college was political economics. This course covered a range of different subjects which now fall within the purview of at least five or six different disciplines. Altman feels that education is structured too narrowly along disciplinary lines, and that integrative and cumulative learning (and the principles of application, interdisciplinary study, and student initiative) should not be left until the end of an undergraduate career to be addressed.

Many undergraduate institutions, including the Gallatin School at NYU and Sarah Lawrence College, agree with Altman’s perspective and are similarly invested in blurring the borders between subjects earlier rather than later in undergraduate study. Altman also cited the case of Ithaca College, where students in their freshman year take a cluster of general education requirements that are organized around a theme (whether its technology or diversity or urban planning). Here, even in their first semester, students are encouraged to see how different disciplines can be collaboratively oriented towards one particular issue or problem. This encourages students to start thinking early across disciplinary lines and forming critical connections throughout their coursework. Altman feels that students would benefit greatly from such an effort to create effective vehicles that enable them to not only learn but apply their knowledge throughout the course of their study, rather than be asked to do it all at once in a single project at the end. However, he notes, tenure is not based on excellence in undergraduate teaching but on publications, which leaves little incentive for innovation in undergraduate teaching. He also noted that K-12 teaching is still largely oriented towards standardized exams, and that students are rewarded for memorization and regurgitation rather than critical thought. Like Schweitzer, Altman indicated that there is a dissonance between what teachers feel is quality education at the classroom level and the characteristics and statistics sought by assessment committees.

Many undergraduate institutions, including the Gallatin School at NYU and Sarah Lawrence College, agree with Altman’s perspective and are similarly invested in blurring the borders between subjects earlier rather than later in undergraduate study. Altman also cited the case of Ithaca College, where students in their freshman year take a cluster of general education requirements that are organized around a theme (whether its technology or diversity or urban planning). Here, even in their first semester, students are encouraged to see how different disciplines can be collaboratively oriented towards one particular issue or problem. This encourages students to start thinking early across disciplinary lines and forming critical connections throughout their coursework. Altman feels that students would benefit greatly from such an effort to create effective vehicles that enable them to not only learn but apply their knowledge throughout the course of their study, rather than be asked to do it all at once in a single project at the end. However, he notes, tenure is not based on excellence in undergraduate teaching but on publications, which leaves little incentive for innovation in undergraduate teaching. He also noted that K-12 teaching is still largely oriented towards standardized exams, and that students are rewarded for memorization and regurgitation rather than critical thought. Like Schweitzer, Altman indicated that there is a dissonance between what teachers feel is quality education at the classroom level and the characteristics and statistics sought by assessment committees.

Some central questions obviously remain about undergraduate capstone courses. Some faculty I spoke with felt that while entry-points in a major can be structured, upper-level courses should be taken laterally, and the student should be able to decide which 300 and 400 level courses to take and when to take them. These professors felt that laterally structured (or less structured) majors do not preclude integrative or critical thinking, and that capstone courses are too difficult to implement, manage, and grade. Underpinning such a perspective is also the question: to what extent are undergraduates supposed to specialize? And does specialization indicate deep study in one area, or does it emphasize the interconnectedness of that area with others? Beyond the many logistical issues, including class size, faculty to student ratio, grading (particularly in group-work situations), reporting and records, it can also be asked how a capstone can be implemented across a major in a uniform way, especially outside the sciences. Additionally, it seems that capstone and exit-point courses are too often mandated for assessment purposes, and therefore are not sufficiently geared toward principles of student initiative and integration associated with capstone learning. And finally, there is the critique that these principles should be implemented throughout undergraduate instruction rather than jammed into a cursory course supposed to mark the end of a major. While many of the opinions I encountered at CUNY are consistent in maintaining that vertically structured learning and capstone experiences are a very good idea for students, a great deal of dissatisfaction underlies these contentions. While some capstone experiences are, I’m sure, as effective as they are made to sound, it seems a lot more could be done towards emphasizing critical ability, integration, individual supervision, and student initiative at all tiers.

Some central questions obviously remain about undergraduate capstone courses. Some faculty I spoke with felt that while entry-points in a major can be structured, upper-level courses should be taken laterally, and the student should be able to decide which 300 and 400 level courses to take and when to take them. These professors felt that laterally structured (or less structured) majors do not preclude integrative or critical thinking, and that capstone courses are too difficult to implement, manage, and grade. Underpinning such a perspective is also the question: to what extent are undergraduates supposed to specialize? And does specialization indicate deep study in one area, or does it emphasize the interconnectedness of that area with others? Beyond the many logistical issues, including class size, faculty to student ratio, grading (particularly in group-work situations), reporting and records, it can also be asked how a capstone can be implemented across a major in a uniform way, especially outside the sciences. Additionally, it seems that capstone and exit-point courses are too often mandated for assessment purposes, and therefore are not sufficiently geared toward principles of student initiative and integration associated with capstone learning. And finally, there is the critique that these principles should be implemented throughout undergraduate instruction rather than jammed into a cursory course supposed to mark the end of a major. While many of the opinions I encountered at CUNY are consistent in maintaining that vertically structured learning and capstone experiences are a very good idea for students, a great deal of dissatisfaction underlies these contentions. While some capstone experiences are, I’m sure, as effective as they are made to sound, it seems a lot more could be done towards emphasizing critical ability, integration, individual supervision, and student initiative at all tiers.