Clifford D. Conner

Salami tactics are how devious politicians attempt to achieve major policy goals that they don’t dare pursue openly and directly. Knowing that they can’t have the whole salami all at once, they lop off one small sliver at a time. If successful, they eventually attain their objective by a series of incremental, irreversible steps.

Salami tactics are how devious politicians attempt to achieve major policy goals that they don’t dare pursue openly and directly. Knowing that they can’t have the whole salami all at once, they lop off one small sliver at a time. If successful, they eventually attain their objective by a series of incremental, irreversible steps.

One policy goal that some American military strategists would like to achieve is the use of nuclear weapons in combat. As Barack Obama acknowledged in 2009, the United States is “the only nuclear power to have used a nuclear weapon.” But since the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, nuclear weapons have, by the greatest of good fortune, remained on the shelf.

A Brookings Institution audit estimated that the United States spent more than nine trillion dollars on nuclear weapons between 1940 and 1996. We must be thankful that the fruits of those trillions were, metaphorically speaking, flushed down the toilet rather than used on the battlefield.

That is not to say, however, that nuclear weapons have not been used since 1945. To the contrary, they have been used hundreds of times by several nations to intimidate other nations. In August 2017, when Donald Trump threatened to unleash “fire and fury” against North Korea, that was but one in a long string of uses to which the most potent of the world’s thermonuclear arsenals has been put.

During several decades of Cold War, the U.S. and Soviet nuclear arsenals were used to provide cover for a number of proxy wars between the two superpowers. The nuclear “balance of terror” allowed for the decimation of populations of smaller allies without causing annihilation of the primary combatants. The long years of the U.S. war in Southeast Asia claimed the lives of an estimated three to four million men, women, and children, none of them killed outright by nuclear weapons.

Restoring the Nuclear Option

The horror of the instantaneous incineration of two Japanese cities and tens of thousands of civilian lives made a lasting impression on public consciousness that has thus far sufficed to deter a recurrence. But ever since the end of World War II there have been unrelenting calls to restore the nuclear option to routine warfare.

Among the most persistent advocates was General Curtis LeMay, who had directed the March 1945 firebombing of Tokyo. LeMay boasted, with characteristic callousness, that his forces had “scorched and boiled and baked to death more people in Tokyo on that night of March 9–10 than went up in vapor at Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined.”

U.S. Air Force General Curtis LeMay

Later, in the early stages of the Cold War era, General LeMay headed the Strategic Air Command, which put him in charge of the U.S. nuclear strike forces. Typifying the kill-it-in-the-cradle instincts of the military mind, he lobbied for massive preemptive nuclear strikes against the Soviet Union, despite the Strategic Air Command’s own estimates that it would annihilate more than 77 million people in 188 targeted cities. Fortunately, President Eisenhower overruled him and disallowed preemptive strikes. All of that was prelude to what was probably LeMay’s most notorious utterance when, as the Vietnam War was escalating, he announced his desire “to bomb them into the Stone Age.”

Strategic versus Tactical Nukes

The central ploy in the salami campaign to undermine antinuclear resistance aims at convincing the public that smaller “tactical” bombs—as distinct from larger “strategic” ones—are no big deal. Proponents of tactical nukes claim that they could be safely deployed in “regional wars” without triggering a massive, planet-engulfing nuclear Armageddon.

The central ploy in the salami campaign to undermine antinuclear resistance aims at convincing the public that smaller “tactical” bombs—as distinct from larger “strategic” ones—are no big deal. Proponents of tactical nukes claim that they could be safely deployed in “regional wars” without triggering a massive, planet-engulfing nuclear Armageddon.

Downplaying the dangers of tactical nuclear weapon use is designed to set a precedent—to get the camel’s nose under the tent, so to speak. As of this writing, the effort has not yet succeeded in bringing about the direct use of such weapons, but the campaign to legitimize them continues and the pressure is mounting. Tactical weapons are supposedly intended for smaller tasks than their strategic counterparts, such as knocking out bridges rather than, say, flattening major cities. The distinction between strategic and tactical, however, is arbitrary, to say the least. A leading proponent of combat nukes, Defense Secretary James “Mad Dog” Mattis, proclaimed there is “no such thing” as a tactical nuclear weapon. “Any nuclear weapon used anytime is a strategic game changer,” he acknowledged at a February 2018 Congressional hearing.

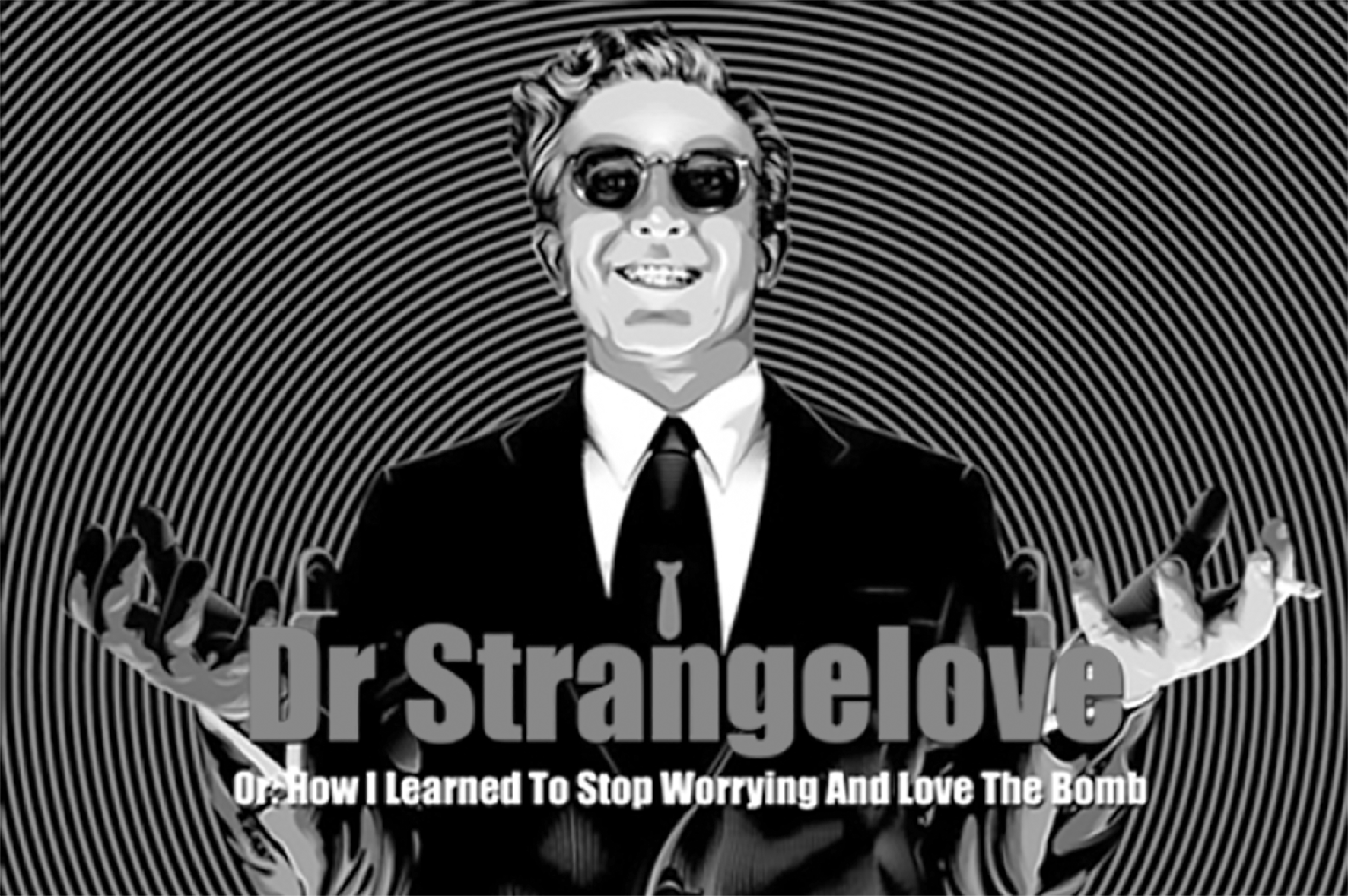

Although the drive to normalize battlefield nuke use has recently reached new and alarming heights, it is not a new development. The promotion of tactical nukes had already reached fever pitch in the 1960s. Herman Kahn, doyen of the military-industrial complex’s favorite think tank, the RAND Corporation, was the model for Stanley Kubrick’s wickedly satirical Dr. Strangelove, urging the public to “stop worrying and love the bomb.”

Kahn hailed the usefulness of smaller nukes in his seminal On Escalation, which argued that they were necessary to create “gradations” in responses to threats from enemies. They would, Kahn contended, allow the generals to escalate wars while maintaining “escalation control.”

From Davy Crockett to Dial-a-Yield Nukes

The pioneer of tactical nukes appeared in 1961, bearing the name of an American frontier hero with pop culture name recognition, Davy Crockett. The Davy Crockett was a portable bazooka that featured the smallest-yield nuclear warhead the Pentagon has ever created. Though tactical nukes pack a smaller punch than their strategic cousins, their destructive power is small only in a relative sense. The 51-pound Davy Crockett could produce a blast equivalent to 10 to 20 tons of TNT. While that was only about one percent of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, it matches the explosive power of the largest of the conventional bombs in the U.S. arsenal. But measures of explosive power in TNT equivalents don’t tell the whole story of the nukes’ lethality. Their killing capability is not only a function of the power of their blast but also of the long-term environmental poison they leave in their wake in the form of lethal radiation. In Hiroshima and Nagasaki, tens of thousands of people died from radiation poisoning in the months and years after the atomic bombs were dropped.

The pioneer of tactical nukes appeared in 1961, bearing the name of an American frontier hero with pop culture name recognition, Davy Crockett. The Davy Crockett was a portable bazooka that featured the smallest-yield nuclear warhead the Pentagon has ever created. Though tactical nukes pack a smaller punch than their strategic cousins, their destructive power is small only in a relative sense. The 51-pound Davy Crockett could produce a blast equivalent to 10 to 20 tons of TNT. While that was only about one percent of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, it matches the explosive power of the largest of the conventional bombs in the U.S. arsenal. But measures of explosive power in TNT equivalents don’t tell the whole story of the nukes’ lethality. Their killing capability is not only a function of the power of their blast but also of the long-term environmental poison they leave in their wake in the form of lethal radiation. In Hiroshima and Nagasaki, tens of thousands of people died from radiation poisoning in the months and years after the atomic bombs were dropped.

A small squad of soldiers could tote the Davy Crockett around in the field, set it up on its tripod, and fire off its nuclear “cannonball” at will. Historian of science Alex Wellerstein summarized the device’s career in a blog post several years ago: “The Davy Crockett system was actively deployed from 1961 through 1971. The redoubtable Atomic Audit reports that they were found to be highly inaccurate and were not effectively integrated into actual war plans. Nonetheless, according to the same source, some 2,100 warheads for the Davy Crockett system were produced, at a cost of about half a billion (1998) taxpayer dollars.”

Although the Davy Crocketts no longer exist, there are still tactical nukes aplenty, and the Pentagon continues to include them in their plans. The distinction between large strategic and small tactical weapons is further blurred by the fact that the same device—most notably, the B61 bomb—can serve as both. The B61 is the primary thermonuclear gravity bomb in the U.S. arsenal. It is a variable-strength (“Dial-a-Yield”) bomb that can be set to yield anywhere from 0.3 to 340 kilotons, or from about twice the potency of the Davy Crockett to about 22 times that of the Hiroshima bomb.

Loading a B61 thermonuclear bomb onto an F-16 fighter-bomber

A variant of the B61, the W80 warhead modified for use with air-launched cruise missiles and Tomahawk missiles fired from ships and submarines, also had Dial-a-Yield capability. It can explode with TNT equivalence of from 5 to 150 kilotons. The Navy’s tactical nukes were “retired” in 2010, but their advocates, with encouragement from the Trump administration, continue to lobby for their return.

The 21,600-pound Mother Of All Bombs

In April 2017, MOAB, the famous “Mother Of All Bombs,” was dropped in a rural district of Afghanistan—the first combat use of the largest non-nuclear bomb in the U.S. arsenal. It was an especially ominous event because the decision to experiment with the explosive power of the mega-bomb was taken unilaterally by General John Nicholson, the commanding general of U.S. forces in Afghanistan. In praising that decision, President Trump declared that he had given “total authorization” to the U.S. military to conduct whatever missions they wanted, anywhere in the world. That declaration seemed to issue an open invitation for field commanders to fire off a tactical nuclear warhead. Will that be the next slice of the combat experimentation salami?

The Obama-Trump Nuclear Modernization Program

In October 2009, President Barack Obama signed a National Defense Authorization Act to “modernize the nuclear weapons complex,” a commitment to spending some $300 billion over the following ten years to upgrade and expand the American nuclear arsenal. In addition to replenishing the stockpile of nuclear warheads per se, the plan called for 12 new nuclear-capable submarines, 100 new bombers, and 400 new intercontinental ballistic missiles to deliver them. The $300 billion was just the initial estimate; the 30-year cost of the upgrade was projected to be well over a trillion dollars. This major escalation of the arms race was carried out by a president who had won office after promising that nuclear disarmament would be a central goal of his administration. In April 2009, the newly-elected Chief Executive publicly vowed, “I state clearly and with conviction America’s commitment to seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons.” Those were fine words, for which six months later, in October, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. But before the month of October had ended, the new Nobel laureate had signed into law the act initiating the trillion-dollar-plus expansion of the U.S. nuclear arsenal.

There was no admission of a flip-flop. Obama said he continued to seek disarmament, but was obliged to negotiate from a position of strength, which required a reliable, modernized U.S. arsenal. Obama’s disarmament legacy was to turn over authorization for unprecedented expenditures on nuclear weapons to the warhawks of the Trump administration, who swiftly dispensed with the pretense that the upgrade was actually in the interests of disarmament. Secretary of Defense Mattis declared that “recapitalizing the nuclear weapons complex of laboratories and plants” was “long overdue.”

As of February 2018, the U.S. arsenal contained about 500 tactical nukes, 200 of which were deployed with aircrafts in Europe and the rest in the United States. The Obama-Trump upgrade calls for creating two new types of tactical nukes: a warhead for submarine-launched ballistic missiles and a sea-launched cruise missile. An analysis of the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review reports that it “bristles with plans for new low-yield nuclear weapons.” Moreover, as a recent article by David Sanger and William Brand in the New York Times notes, “critics of the low-yield weapons say they blur the line between nuclear and non-nuclear weapons, making their use more likely,” and “the Trump policy explicitly threatens to launch nuclear strikes in response to acts of terrorism and to cyberattacks.”

Normalizing the use of smaller nukes would provide the generals with political cover for their entire stockpile of nuclear weapons, small and large alike. To buttress his contention that “a low-yield nuclear weapon is a must-have, not a luxury,” Albert Mauroni, an Air Force think tank director, argues that “eliminating tactical nuclear weapons could result in the U.S. government self-deterring itself from using larger nuclear weapons in a future crisis against another nuclear-weapons state.” “Given,” he continues, “that the U.S. military is increasingly involved in numerous conflicts all over the globe, can it afford to not invest in low-yield nuclear weapons and delivery systems?” The more urgent question is: Given the existential threat thermonuclear war represents, can humanity afford a nuclear-armed U.S. military aggressively pursuing conflicts all over the globe?

Normalizing the use of smaller nukes would provide the generals with political cover for their entire stockpile of nuclear weapons, small and large alike. To buttress his contention that “a low-yield nuclear weapon is a must-have, not a luxury,” Albert Mauroni, an Air Force think tank director, argues that “eliminating tactical nuclear weapons could result in the U.S. government self-deterring itself from using larger nuclear weapons in a future crisis against another nuclear-weapons state.” “Given,” he continues, “that the U.S. military is increasingly involved in numerous conflicts all over the globe, can it afford to not invest in low-yield nuclear weapons and delivery systems?” The more urgent question is: Given the existential threat thermonuclear war represents, can humanity afford a nuclear-armed U.S. military aggressively pursuing conflicts all over the globe?

In October 2017, more than 240,000 troops in at least 172 countries and territories were waging “America’s Forever Wars,” the New York Times reported. U.S. forces were “actively engaged” not only in Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, and Syria, but also in Niger, Somalia, Jordan, Thailand, and elsewhere. “An additional 37,813 troops serve on presumably secret assignment in places listed simply as ‘unknown.’ The Pentagon provided no further explanation.” Congressional oversight of these activities no longer merits even lip service. Opportunities for field commanders to launch a tactical nuclear warhead are thus proliferating. The danger to humanity is incalculable. Despite the salami slicers’ denials, even the smallest thermonuclear exchange is rife with doomsday potential. It is incumbent upon civil society to mobilize massive opposition to the irreversible step of exploding a tactical nuke on an active battlefield.

Science for the People, a leading radical science magazine, was originally published from 1970-1989. Activists are planning a relaunch of the magazine, including republication of its complete archives, beginning later in 2018. For more information on Science for the People’s activities and archives, please visit their website (scienceforthepeople.org/index.php/publishing).

Spot on and ill add you some, Israel provided Saudi Arabia tactical nukes and dropped one maybe two on Sanaa Yemen in 2015.

Amigo, todo lo que sel vio en Yemen apunta a una bomba termobarica, de ser nuclear, nunca se podria haber registrado nada por medios electronicos, ya que el pulso electromagnetico generado por la detonacion, hubiera arruinado todos los dispositivos de registro.