Elizabeth Foley

The most consequential midterm elections in modern American history are now over, and assuming Trump doesn’t send troops to blockade the doors of the Capitol building against this young, diverse caravan of new legislators, Congress will convene in January with Democrats in control of the House for the first time in eight years. There will be a temptation to embrace this circumstance as a much-longed-for return to normalcy, but it isn’t one. Republicans have tightened their grip on the Senate, and those who now work there are even less normal than they were before the midterms. I’m not a full-on Nancy Pelosi hater like some on the Left – the Affordable Care Act wouldn’t be law without her, for one thing – but her recent talk of bipartisanship in the coming session is disturbing, even if it’s merely a rhetorical feint. Any Democrat in Congress who doesn’t understand what motivates the Republican party at this late date really has no business keeping his or her seat. What’s plaguing Republicans isn’t some temporary ethnopopulist fever that will dissipate if only Democrats speak soothingly and apply cold compresses to their opposition’s foreheads. This disease is structural and terminal, and Democrats’ first concern should be to keep the Republican cancer from spreading to the larger body politic.

The most consequential midterm elections in modern American history are now over, and assuming Trump doesn’t send troops to blockade the doors of the Capitol building against this young, diverse caravan of new legislators, Congress will convene in January with Democrats in control of the House for the first time in eight years. There will be a temptation to embrace this circumstance as a much-longed-for return to normalcy, but it isn’t one. Republicans have tightened their grip on the Senate, and those who now work there are even less normal than they were before the midterms. I’m not a full-on Nancy Pelosi hater like some on the Left – the Affordable Care Act wouldn’t be law without her, for one thing – but her recent talk of bipartisanship in the coming session is disturbing, even if it’s merely a rhetorical feint. Any Democrat in Congress who doesn’t understand what motivates the Republican party at this late date really has no business keeping his or her seat. What’s plaguing Republicans isn’t some temporary ethnopopulist fever that will dissipate if only Democrats speak soothingly and apply cold compresses to their opposition’s foreheads. This disease is structural and terminal, and Democrats’ first concern should be to keep the Republican cancer from spreading to the larger body politic.

In talking about Republicans, it’s important to make a distinction between the Republicans in Congress and the voters who put them there, a majority of whom presumably also voted for Trump. These voters’ emotional investment in racism and xenophobia appears in many cases pathetically earnest, a naivete so ingrown as to be completely incapable of recognizing its own malignancy. Their Congressional representatives, however, run the sincerity gamut from true white nationalist believers like Iowa’s Steve King (who regrettably survived a serious midterm challenge) to calculating cynics like Mitch McConnell. Whether or not McConnell is personally racist, he is always ready to make political hay from the racism of his own constituents in Kentucky and the constituents of the Senate colleagues whom he corrals and directs.

Nevertheless, Trump voters and the Republican party are each gripped, at their respective tiers of establishment power, by a common fear of the demon that lurked ominously in the background of the 2016 and 2018 elections: certainly not widening income inequality, which the Republicans blatantly favor and celebrate, but demographic change. I don’t know how many Trump voters are familiar with the widely-cited projection that by 2044 (or perhaps sooner), the U.S. will no longer be a majority-white nation. Even those who are ignorant of the precise nature of the coming statistical shift, however, have been forced to notice the visitor from that diverse future who recently finished an eight-year stint in the White House. To an unknown but clearly significant number of white Trump voters, Obama portends a country full of black and brown people who are better educated, more demonstrably talented, and more replete with corresponding opportunities than they themselves are. (Obama is more demonstrably talented than the vast majority of people, but if you don’t have a broad base of nonwhite local acquaintances or colleagues within which to contextualize him, how can you be sure he doesn’t represent some kind of terrifyingly accomplished new normal?).

These nonwhite interlopers are poised to “jump the line” (a time-honored anti-affirmative action metaphor recently reinvigorated by the Louisianans profiled in Arlie Hochschild’s Strangers in Their Own Land) in which their own families have been waiting, with varying combinations of resentment and resignation, for generations or centuries, for their share of economic and political power. Now these beleaguered white people will have even less chance of getting that power. They will be looked down upon not only by the white elites to whose scorn they are accustomed (and which they to some degree relish), but by a newly-empowered class, composed of people of color, who will immediately seize the chance to mock the misfortunes of non-elite whites and exact belated revenge for the historical wrongs of which all present-day whites are (naturally) entirely innocent. Under the circumstances, Hillary Clinton’s klutzily middle-class whiteness – less shape-shifting and subversive than her husband’s – might have comforted such voters had it not been so entirely offset by the tsunami of intersectional hatred she inspires as a Clinton who is also a woman. For Hillary, who embodied two kinds of threat at once, to have taken the reins directly from Obama would have meant two “affirmative action” presidencies in a row. That they emerged from two noticeably distinct political locations within the Democratic party might have suggested that the U.S. had changed both broadly and deeply, for real and perhaps for good. In response, Trump voters acted in an instinctive consensus to prevent anything of the kind from happening.

The Republican party, meanwhile, has also seen the writing on the wall regarding demographic change; its response was to blanch and run in the opposite direction. Since its losses in the 2006 midterms, and as recently as the 2016 primary season, the party has been issuing periodic internal postmortems warning itself that it must change with the changing demographics of the country or cease to win elections. In practice, this means that Republicans must court Latinos, the single fastest-growing demographic in the U.S. But doing this would require adopting an immigration policy that acknowledges that Mexicans, Salvadorans and Hondurans are rational human actors responding to legitimate economic and political forces in their homelands who continue to behave as rational human actors once they arrive in the U.S. And this is precisely the admission that the existing Republican base of voters, with its heavy concentration of older white people, can least tolerate from the party establishment. To expand its outreach to Latino voters while still holding onto white voters who feel threatened either personally or existentially by immigration would require a level of political skill, a precision of execution and a strength of conviction that the party apparently does not believe itself to have. Republicans thus weigh their party’s long-term health in a balance with the short-term ecstasy of the tax cuts, brazen government deregulation, and right-wing court packing that Trump is already delivering. Even in a best-case scenario, acting constructively to secure the party’s future has been, and remains, a hellishly difficult project for the Republican establishment. Given the choice between that excruciating business and today’s temporary heaven, how was it ever a question which one they would pick?

Ever since the leftist political movements of the 1960s threatened to remake the American political landscape, conservative Republicans have been in revolt against the notion that they might actually have to share power with people of color, white women and (double ugh) non-plutocrats. But the political and financial spoils that the party could reap from control of the last superpower standing and the biggest economy in the world, made it pragmatic for them to keep playing by the democratic rules that began to feel particularly onerous and self-limiting in the wake of the civil rights and women’s movements. If you’ve ever wondered why the most fanatical small-government conservatives don’t just buy an island, retreat to it and set up the market-loving minimalist government of their dreams there, this is why: barring the local discovery of oil, Wakandan vibranium, or some other resource that would enable these American exiles to hold the energy economy hostage, their island paradise could only ever play a miniscule role in the world market. It’s also why democracy-averse conservatives don’t just cut their losses in the U.S. and try to infiltrate, for personal gain, the existing government of some Latin American or African nation where the democratic institutions are of newer and more vulnerable vintage and where the citizens have already been conditioned, however unhappily, to tolerate visible corruption. There’d be the pleasure of local control, but relatively little money or international clout in it. So Republicans have put up with democratic constraints, because the money and power that have flowed from operating within them have thus far been worth it.

But time and demographic change have conspired to make democratic processes more and more unmanageable for the GOP, particularly voting. Egregious voter suppression tactics were on display during the midterm campaign season in locations from North Dakota, where interference with the Native American vote may indeed have cost Heidi Heitkamp her Senate seat, to Georgia and Florida, where black voter-roll tampering was necessary, and all too successful, in keeping Stacey Abrams and Andrew Gillum out of the governors’ mansions. And these cases are only the tip of a larger iceberg. Two important recent histories of the ongoing American battle for voting rights, Ari Berman’s Give Us the Ballot and Carol Anderson’s One Person, No Vote, make clear that the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which finally gave real teeth to federal efforts to ensure black voters’ access to the ballot, has stubbornly remained in Republicans’ crosshairs ever since its passage. In 2013 they succeeded, via the Roberts Supreme Court, in striking down the key provision of the Act that required states with a history of voter discrimination (which, if we’re being real, is all of them) to get preclearance from the federal government before changing their voting laws. This means that states can now pass any number of terrible new laws and wait for someone to sue to strike them down. In the meantime, critical elections that nail further voting-related chicanery into place are occurring without input from the excluded voters.

States under Republican control promptly went to town on measures to keep Democratic voters from the polls, particularly people of color and poor people. In case it wasn’t already clear from the headlines of the last five years (and the last five months), Berman and Anderson make the case, in convincing and enraging detail, that voter suppression and gerrymandering are not incidental or supplemental to the GOP’s election strategy: they are now among its most essential tools. Drafting all those voter ID laws, preparing all those court challenges, masterminding all those redistricting efforts is an enormous pain in the ass, but Republicans push these measures through because they have to. They can’t win on the national level without these artificial advantages and haven’t been able to since the Reagan-H.W. Bush years. Republicans do not appear to have a long-term electoral strategy that is compatible with democratic methods. What they have instead is Trump and the last-ditch power grab he offers.

Republicans might privately scorn Trump’s volatility, vulgarity and incompetence, but backing him is their main hope for consolidating their own and the party’s power, so they back him. They might prefer to make empirically sound arguments for their positions, but data has long since ceased to support many of those positions, so data and evidence, not their stances, need to be thrown out the window. (For some conservatives, empirically-grounded debate has actually been a difficult reflex to stamp out; you can see this on right-wing Twitter even now, when regular schmucks with imperfect mastery of the Trumpian zeitgeist try to use supporting evidence, however flimsy, to make a case for their views. It makes them look like relics, or worse, academics. Don’t they know that deferring to evidence is the elitists’ M.O.?) Republicans might also prefer to craft talking points that don’t contradict one another – like denying that Trump and Brett Kavanaugh perpetrated bad stuff like collusion and attempted rape, while simultaneously insisting that these are harmless and non-actionable behaviors – but coherent arguments are luxuries they can no longer afford. Any rhetorical port in a storm at this desperate stage will do. Their voters likewise understand that the means don’t matter, only the ends of Republican minority rule and “owning the libs” do. Some of these voters, after all, see themselves as engaged in a life-or-death struggle for (white, Christian) cultural supremacy that parallels their party’s fight for its political life. These besieged citizens already know they need to cast off any baggage that will hamper them in this fight, up to and including empirical reality itself.

Viewed through this lens, all the seemingly hypocritical, humiliating and self-destructive things that Republicans have done under Trump are utterly logical. They do these things because they must, because they’re sincerely afraid they can’t hold onto power in any other way and their party’s ability to manipulate elections, though rapidly advancing, is still far from reliable. But what really gives the game away is the elephant in the room, one whose full shape is so eyeball-searing that we can’t take it in whole, but only squint a little at its ears and tail: the fact that an enemy state not only wished to install our current leadership for us, but also succeeded. Anyone who was alive during or immediately after the Cold War will remember its reflexive demonization of all things Soviet. It was similar to today’s vilification of Muslims, sans racialization. These sorts of ideological hatreds normally take eons to dissipate, long outlasting the political context in which they were initially useful. But the same Republicans who have publicly venerated Ronald Reagan as the ultimate anti-Communist crusader – some of whom, like Jeff Sessions, were around at the time and tried to work for him – are unoffended by the most genuinely sinister figure to take control of Russia since Khrushchev. This too, though insane on its face, is logical: Republicans now find that Russian assistance may be of critical importance in keeping their own seats, whether that assistance arrives directly (as seemed to be the case with California’s Dana Rohrabacher – thankfully just defeated, but surely others among his peers can be drafted to take his place) or funneled through the National Rifle Association (and how many Congressional Republicans are there who have not received money and endorsements from the NRA?). In fact, Russian election interference dovetails beautifully with the voter suppression tactics the GOP is already leaning on so heavily. It would be surprising, under the circumstances, if Republicans weren’t on board with it.

We’re shocked at the about-face this behavior appears to represent – but how much of an about-face is it, really? If the Republican party’s ostensible historical commitment to democratic governance is just a cover for the real prize, managing the wealth and power associated with governing the United States, then democratic government has been merely incidental to Republicans’ calculations, except insofar as democracy provides a more attractive cover for their consolidation of power than, say, Turkish autocracy would. They’ve never had to choose between democracy and power before, but with their voter base shrinking and their plans to decimate the social safety net lacking in majority support, now they do. So the party has chosen power over democracy, and it will not change course unless and until it is forcibly stopped. Republicans are never going back to “normal,” a state that at its modern best was never very good anyway. The Left cannot continue to behave as if the GOP would be manageable if only they controlled a smaller piece of government. Containment of the Republican threat is a necessary first step, but isn’t a long-term solution. A cornered party, bleeding from life-threatening wounds, will do anything and everything to regain not just its footing, but its dominance. After all, Republicans took back the House in the 2010 midterms from a position of far greater disadvantage than their current one, and look what they’ve parlayed that victory into since then.

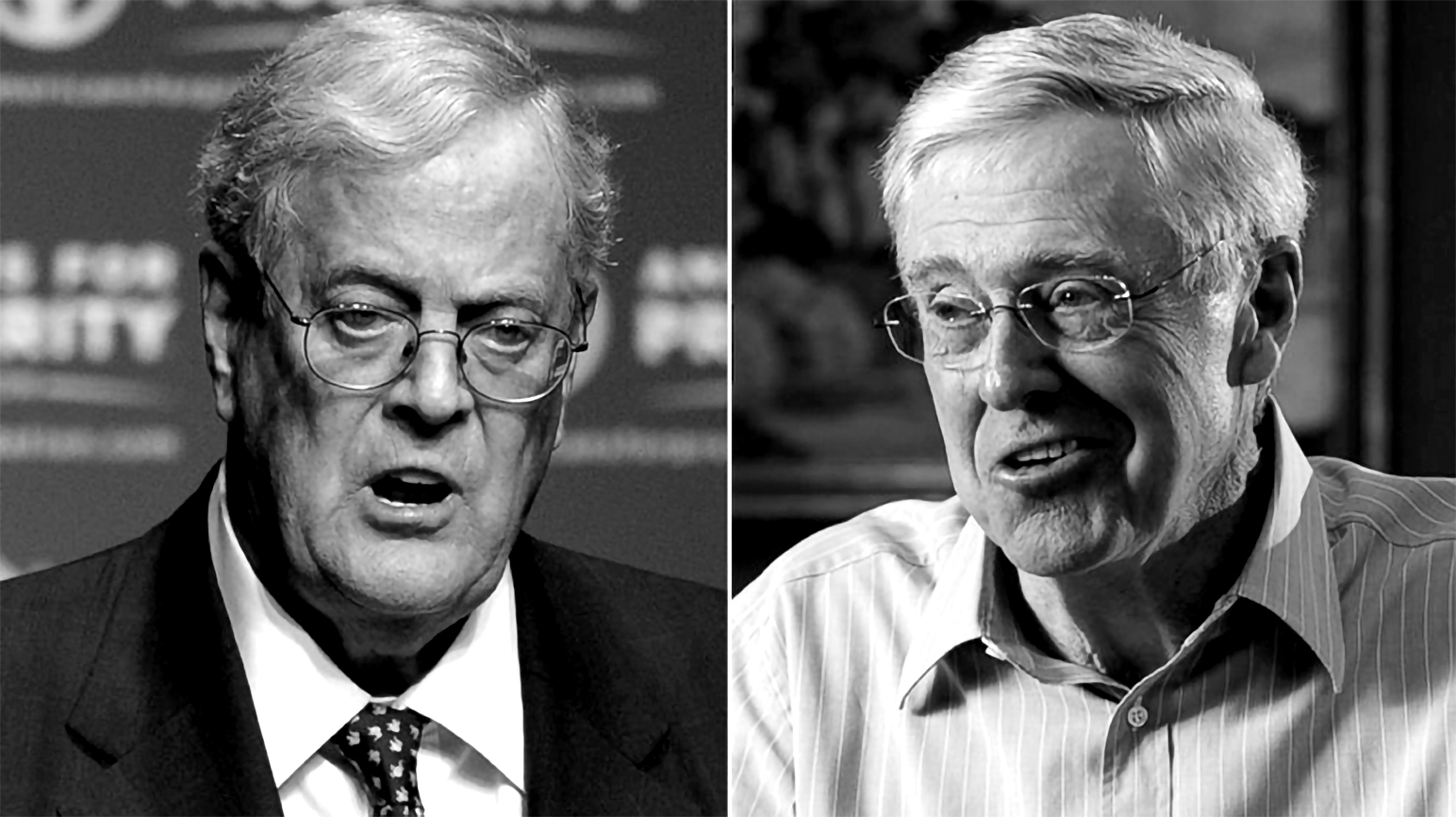

Speaking of the 2010 midterms, I haven’t even mentioned the Koch brothers yet. I use “Koch brothers” here as a synecdoche for “radical right-wing billionaires,” a cohort that goes beyond Charles and David Koch. But they have certainly been this group’s ringleaders. If you’ve read Lee Fang’s book The Machine or Jane Mayer’s book Dark Money, you already know that the Kochs, owners of the second largest private company in the U.S. and probably the two most powerful environmental despoilers and climate-change deniers on the planet, have for forty years been building a network of seemingly unconnected libertarian and far-right think tanks, foundations and shell organizations. This network has gradually, vampirically taken over the Republican party, with a major assist from the 2010 Citizens United Supreme Court decision that opened the floodgates to unlimited campaign contributions from all sorts of unaccountable private entities. Though the populist anger that propelled the Tea Party was real, it was Koch funding that gave it organizational structure, training and direction. The Tea Party, in turn, drove already ultra-conservative politicians like Eric Cantor and John Boehner out of Congress and replaced them with nihilist toddlers who thought it would be fun to crash the world economy in retaliation for the government’s nerve in passing the Affordable Care Act.

Charles Koch, long the brains of the Koch operation and more so now that David is technically retired, has contemptuously remarked that he sees politicians as mere actors playing out a script. This comment might make you wonder why self-respecting Republicans would sign up to become interchangeable pawns in the Koch game. First of all, the GOPers now holding power aren’t self-respecting Republicans, or perhaps they believe they can temporarily trade their self-respect for a boost into powerful positions that one day won’t rely on Koch support. That day will never come, but it’s probably what Mike Pence, the Kochs’ preference for president over the entire field of 2016 Republican contenders, tells himself daily. This is the one thing I can genuinely appreciate about Trump: though the Kochs have grudgingly made peace with him for now, his willfulness and utter lack of discipline must be almost as maddening to them as to normal Americans who would prefer that the president not start wars over Twitter. The Kochs might even back Trump’s impeachment, if that meant that a President Pence could bring the U.S. armed forces and nuclear arsenal into alignment with the Koch cause.

The other thing that should be said about the Koch-authored script for American government is that it is merely a radicalized and adrenalized version of what Republicans have consistently backed since FDR’s New Deal: no new taxes and get rid of the old ones; an empowered overclass and a disempowered government; corporations über alles. An invaluable 2017 book, Nancy MacLean’s Democracy in Chains, builds upon the work of Fang and Mayer by connecting the Kochs to the ideology of James McGill Buchanan. Buchanan, a Nobel Prize-winning Southern economist who died in 2013, promoted a system of permanent minority rule by the corporate one percent that would take its inspiration from Jim Crow tactics and states’-rights arguments to install state-level fiefdoms answerable to neither federal nor local governments. Democracy in Chains is also about the slow and steady inroads these ideas and their well-funded acolytes have made into academia, a story that should be of interest to all academics. The unified theory MacLean brings to bear on seemingly disparate historical phenomenon is so satisfying that it constitutes a form of intellectual empowerment against the frightening political developments she describes. So many books with alarmist-sounding titles have been published in the wake of Trump’s election that I fear this one might get lost in the shuffle; I can’t recommend it highly enough.

This, then, is what the Left is up against: not merely an opposition party of misguided but redeemable politicians and fellow citizens whose aims we can agree to disagree with, but one whose very survival depends on the abandonment or active destruction of democratic institutions and norms. At this point, the only things Republicans and Democrats still share are a belief in capitalism and certain vestigial habits of democratic thought and behavior that Republicans are already finding relatively easy to jettison. Democrats, for the last two years, have been alone in the democratic arena. Initially they (and we their leftist constituents) were alone and out of power, but even as we retake the House, it’s important to remember that we’ll still be alone: Republicans will not interact with us in good faith. Whether they’d like to or not (and most of them would not), they can’t afford it: their billionaire backers and their voters would turn against them in the blink of an eye. Any Republican politician who actually did have some attachment to democratic ideals and wasn’t beholden to Tea Party backing jumped ship before the 2016 election. Any Republican who does so from this point forward is almost certainly an opportunist positioning him- or herself for a place in the post-Trump political landscape.

Democrats need an opposition party, badly. But the U.S. cannot go forward as a functional republic unless — pardon my uncivil turn of phrase – the Republican party is burned to the ground and rebuilt as, or replaced with, an entity that agrees to stop denying certain political and empirical realities. At a minimum, the replacement party has to acknowledge that climate change is occurring; that immigrants are potential future U.S. citizens (and voters); that people who aren’t rich white men nevertheless have the right to act in their own political interest; and that the U.S. is part of the world. Perhaps the future face of a viable American conservatism will look a lot like Bill Clinton’s Third Way centrism. (Hillary, by 2016, was further left than that: thanks Bernie, thanks BLM, thanks Occupy — and believe it or not, thanks Obama, too. Even if you found Obama intolerably compromised on a policy level, having an actual black president has pretty much obliterated “metaphorical black president” as a viable role for white politicians, who now have to gesture less symbolically in the black community’s direction.).

The Fox News crowd, as currently comprised, will of course never accept such a future for their party. But if Fox itself decided there was no commercial future in red-meat Republicanism and rebranded itself in search of more fruitful markets – their viewers, after all, are mostly aging white people whose supply is not replenishing itself in similar numbers among their grandchildren – the Fox News crowd would have to turn elsewhere for their media needs and would likely fragment. Some of them might end up in even more reactionary niches than Fox, but others might strike out towards normalcy. Such people, given their history, would not exactly constitute a stronghold of democratic values or principles, but the point here for the Left is less to gain their support than to be spared the vehemence of their opposition.

It feels strange, and perhaps politically undisciplined, to be saying something as absolutist as “burn the Republican party to the ground.” The need to paint one’s political opponents with the broad brush of uncomplicated evil is one that belongs to the very young or the stupidly doctrinaire, and in using such language I risk being dismissed as at least one of these things. I also, perhaps, risk dehumanizing Republicans in the same way that Republicans currently dehumanize the Left, calling us an angry mob of animals who deserve to be assaulted, raped, and killed to prepare the ground for the actual violence they may anticipate. But given that racism, misogyny, bullying, and the abuse of power are common human behaviors, I have no wish to suggest that Republicans aren’t human. What makes them dangerous, and what ought to categorically disqualify them from power, is not that they’re inhuman or even that they’re immoral, but that they aren’t democratic. What I don’t fully grasp is why the situation isn’t being framed that way, all day and every day, by the Left and its media organs (the establishment media, including Trump’s favorite dart boards the New York Times, the Washington Post and CNN, do regularly point out the anti-democratic tendencies of his administration, but they are so powerfully invested in the continuing idea of a two-party structure that they reflexively continue to slot the Republican party into a role whose norms it no longer observes).

Such an anti-democratic framing might have a chance of succeeding where the Left’s other arguments have failed. When the Left attacks the Right for being racist (which it is), the attacks don’t hit home because the Left and Right have different understandings of what racism is, such that the Right believes the Left is racist just for addressing the subject of race. When the Left attacks the Right for being anti-woman or for being bullies, the critiques don’t hit home because the Right simply doesn’t care; these things are not sources of shame to them. In any case, all of these evils have thus far been able to coexist, however excruciatingly for their victims, with America’s “democratic” government. Fence-sitters can tell themselves, Sure, racism and power abuses are bad and all, but they didn’t spell the end of the country in 1860 or 1972, and they’re not going to end it now. But if the Left attacked the Right for being anti-democratic, would that get under conservative voters’ skin? Probably not, since they’ve already been inoculated against self-reflection on this point by an Orwellian right-wing rhetoric that paints the Left as anti-democratic. But making the anti-democratic case against Republicans might activate nonvoters, and we could really use their help.

In the meantime, let’s stop wasting time being shocked by the latest Republican assaults on truth, decency, and reality and instead put our energy toward reading between the lines of these events. We should keep in mind that the power the Republican party now holds is in many ways a political illusion, but one that can become real and permanent through both quasi-legitimate and illegitimate means. As morally unpleasant as the exercise may be, we need to put ourselves in their shoes and imagine working under the threat of extinction, against the popular will, and with unlimited funding in order to anticipate what Republicans are likely to do next and plan against it. We still need public anger and critique to remind the undecided and each other that what Republicans are doing is outrageous and dangerous, but that can’t be the extent of our strategy; we can’t get mad at the expense of getting even. But if we take all possible measures to ruin the Republican brand (as the party of corporate values, this is a language they will understand), we could achieve both goals simultaneously. In thought, deed and dollar, we can boycott the product, shame the shareholders and ostracize the affiliates to damage Republicans’ electoral and literal bottom lines. Just as importantly, we need to elect more Democrats who will do the same — which means, among other things, primarying Chuck “It Can’t Happen Here” Schumer in 2020 (unless by some miracle he starts bringing guns to this gunfight instead of knives).

Let’s put “Republican” in the halls of American political infamy next to “KKK,” a task that will be simplified by the ever-shrinking ideological distance between the two. Let’s make Republican Party membership a black mark that candidates struggle to overcome in future elections. Let’s sink the brand so far and fast that Paul Ryan has to remake himself as an independent for his 2024 presidential run. Then let’s drown out his declaration of candidacy with mocking laughter. Above all, let’s make bipartisanship a dirty word until we have two parties that are actually democratic, whether with a small d or a large one.