Valerie Fryer-Davis

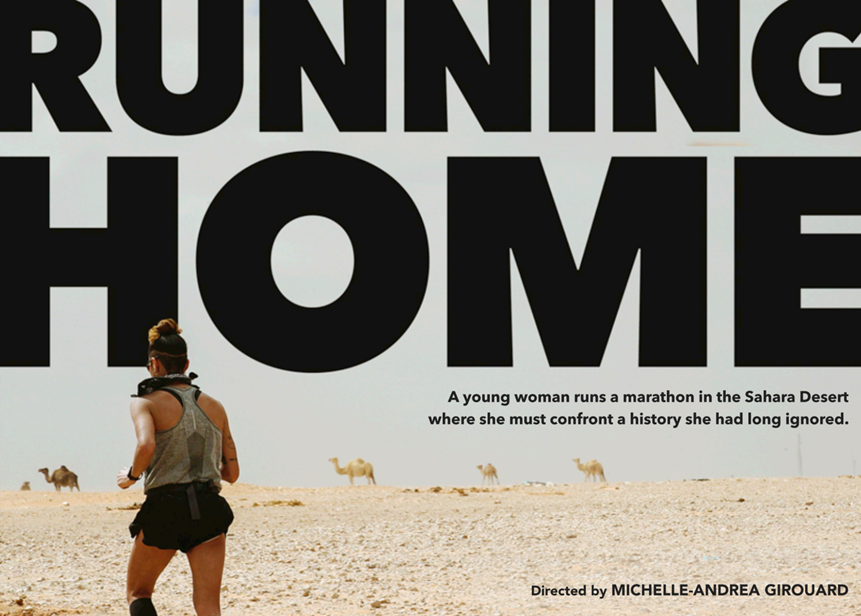

For nearly half a century, the world has ignored Morocco’s illegal occupation of the Western Sahara and the extreme oppression of its people, the Sahrawis. And yet, as Inma Zanoguera Garcias remarks in her documentary, Running Home, as activists we should not try and speak for the oppressed to a global audience. Directed by Michelle-Andrea Girouard, Running Home is a story of finding one’s ancestral roots that documents Inma’s discovery of her birth mother’s Sahrawi origins and her subsequent journey to the refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria, to run a marathon. As Inma tells the viewer, her birth mother, Naima Mohamed Hamad, sought refuge in Spain following Morocco’s occupation of the Western Sahara. After her mother’s death due to cancer, a Spanish family adopted Inma and her siblings. Inma was two when this happened so she has little memory of her mother or her history prior to adoption. It is only when her sister showed her a document with her birth mother’s name and place of birth that Inma began to question the type of life Naima Mohamed Hamad had lived, and the type of life Inma herself could have had in the Western Sahara.

Despite her Sahrawi heritage, Inma never attempts to speak for the Sahrawi people who have lived their whole lives in refugee camps or under oppressive Moroccan rule. After her journey to Tindouf, Inma travels to New York to speak to the United Nations about the injustices committed against the Sahrawi people. Here, she asserts, “I’m not demanding that we give Sahrawis a voice. Sahrawis have and have always had their own clear and loud voices. It is up to us now whether we are going to give ourselves the gift of listening.” Despite a desire to promote this issue on the world stage, Inma reminds her audience that we should never attempt to speak for the oppressed. To do so silences already marginalized people, as postcolonial feminist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak famously argued in her essay, “Can the Subaltern Speak?” Speaking for the oppressed overpowers their voices with one’s own, potentially perpetuating the silences that structures of power impose on them. Instead, we must listen to the oppressed, just as Inma argues the UN must do with Sahrawi voices, framing her activism within a long tradition of postcolonial feminist thought.[1] Inma does not speak for Sahrawis who live under oppressive conditions, but she also does not reject her own voice. Running Home confronts this important tension: how does one center the voices of the oppressed through listening and still tell a story of individual becoming?

Following the call to listen, Inma demands that the UN enforce a referendum to free the Western Sahara from Moroccan occupation—a plea the world has ignored for over forty years. After Spain decolonized the territory in 1975, Morocco immediately annexed approximately 75 percent of the Western Sahara, arguing that the Sahrawis are merely a nomadic ethnic group rather than an independent nation. Due to the Sahrawis’ history of nomadism, the Moroccan government saw the land as empty, ripe to claim for its natural resources. Between 1975 and 1991, Moroccan armed forces fought the Sahrawi Polisario Front, a group formed in the early 1970s that the UN now recognizes as the legitimate representatives for the Sahrawi people. A ceasefire agreement in 1991 halted the heated conflict, but Morocco recently broke this ceasefire on 13 November, 2020, reigniting the war. Throughout these forty years of hot and cold conflict, over 160,000 Sahrawi have been forced into exile. Many of them live in refugee camps in Tindouf, with poor access to water, healthcare, and economic stability. Those Sahrawis who stayed behind in the occupied territory face extreme censorship and torture from the Moroccan police state.

To fight the silence surrounding this human rights catastrophe, the Polisario Front relies on narratives of Sahrawi national identity to assert Sahrawis as a sovereign people on a transnational stage. Film is the primary medium through which Sahrawi images and narratives circulate. However, because there is very little filmmaking infrastructure in the refugee camps, and the Moroccan government censors’ narratives about Sahrawi identity in the occupied territories, the Polisario Front relies on transnational filmmaking efforts to amplify Sahrawi voices. In a recent study of Sahrawi film, Chris Lippard argues that these films are often produced by the Sahrawi diaspora. The films revolve around a return to the ancestral homeland where Western and Sahrawi cultural values collide.[2] Inma’s documentary is one such film that fits within this tradition of Sahrawi diaspora films.

In the film, Inma’s Spanish and Sahrawi histories clash as she moves through different spaces. In one of the opening scenes, Inma remarks that for her and her siblings, “history changed” once they were adopted. Through traveling to the Western Sahara, Inma brings her lived history as a young transnational Spanish woman into conflict with her forgotten Sahrawi history. Movement is central to Inma’s negotiation of these histories, and not only because Girouard structures the story around a marathon, continuously cutting between Inma talking to Sahrawis and her running through the desert and refugee camps. We see Inma move between many different homes in the film: her Spanish home where she grew up, her home in Ohio where she goes to school,[3] and her host family’s home in Tindouf. Inma is constantly on the move. She walks through an airport, sits in a dark bus on the way to the refugee camp, and takes a New York City cab on the way to the UN. As she navigates her different histories, she also traverses the globe, establishing this film within the woman world traveler genre.

Inma is a global woman, but her desire to travel goes beyond the trope of the global citizen. She inherits the need to move through space from her birth mother. Just before the marathon begins, Inma provides some context about Naima Mohamed Hamad’s own marathon: her exodus to Spain. Inma says in a voiceover, “She was fleeing a country she had called home just so she could escape the ruling of foreign countries. So I just picture a lot of fear. And moving forward anyways because you have no choice.” This parallels Inma’s own journey to the Western Sahara: “Running for hours in the desert? Nobody really does that, unless, you know, you have to. I just feel like I have to.” Between these two moments, Inma traces a lineage of women who were compelled to move across spaces. She evokes an image of powerful women resisting global power through movement. For her birth mother, this involved escaping “the ruling of foreign countries” that attempted to define her as less-than-human. For Inma, her movement is about claiming a collective Sahrawi history in a world that might otherwise erase it. Both movements express a desire to live with dignity as Sahrawi women—to be free to travel between spaces—thus honoring the tradition of Sahrawi nomadism.

The freedom to move is central to the Sahrawi identity. After Inma tells the viewer her mother’s story of migration, Girouard asks her from behind the camera, “What is your hope for the marathon?” The camera then cuts to a close-up of Inma’s face as she says, “Be present in every step […] I want it to be whatever it needs to be really.” The close-up framing asks the viewer to deeply engage with Inma on an individual level. It asks us to listen closely to her words and internalize her message of not forcing movement to be any one thing. The marathon is not just about getting from point A to point B; it is also about being present in the movement itself.

Although she addresses the reader on an individual level, Inma’s message is also an expression of collective Sahrawi nationality. Once she says this to Girouard, she says she’s ready for the marathon and walks away. The camera tracks her walking towards the other runners who are surrounded by a crowd of Sahrawi spectators. It seems as though the runners and the spectators embrace Inma into the collective fold at this moment. Meanwhile, a group of children chants, “The king is dead, the king is dead. Western Sahara raises the flag! No alternative, no alternative to self-determination!” Girouard cuts between the runners, a Western Sahara flag waving in the wind, and the children chanting, who also hold small Western Sahara flags. Through these images and the chanting, Girouard brilliantly shows how the marathon is full of political meaning. The marathon is an expression of the Sahrawi desire to be free of occupation. The Sahrawi people want self-determination, they want the death of the Moroccan king, they want to raise their own flag, they want to move freely, and they use the marathon as a platform to express these demands. Bringing together runners from all over the world such as Inma, the marathon becomes a means to spread this nationalistic message beyond the refugee space.

Children chant, “The king is dead, the king is dead. Western Sahara raises the flag! No alternative, no alternative to self-determination!”

In this scene, young women promote Sahrawi nationalism. Clearly, Inma expresses the Sahrawi trope of movement as a young woman. But also, a girl leads the children in their chant for Sahrawi nationalism. The circulation of Sahrawi nationalism is gendered. In an analysis of the history of Sahrawi gender roles, Konstantina Isidoros reveals how women have always been the bearers of cultural memory. Sahrawi group feeling, or asabīya, is matrilineal and has always been tied to resistance to foreign colonizers, whether that be Spain or Morocco.[4] And as scholars Claudia Barona and Joseph Dickens-Gravito argue, women have historically been central to protesting and founding illegal Sahrawi organizations within the occupied territory.[5] Inma’s circulation of Sahrawi voices at the UN, and the children’s demands for Sahrawi nationalism, thus fit within a broader tradition of powerful Sahrawi women promoting national unity in order to resist foreign oppressive powers.

In recent years, however, diaspora scholars have noted how the Polisario Front might privilege women’s voices, specifically women in the diaspora, to construct a particular image of Sahrawi women. This image is patriarchal and might force Sahrawi women who have grown up abroad to unfairly conform to it. Sociologist Silvia Almenara-Niebla observes this phenomenon on social media, revealing how Sahrawi women who live in Spain often feel pressure from Sahrawi relatives on Facebook to cover their hair, dress modestly, and not participate in a Western lifestyle. Almenara-Niebla argues that online gossip attempts to regulate women’s bodies, which is why many Sahrawi women living abroad will have two Facebook accounts, one for family and one for their Spanish friends. In this way, Sahrawi women can circumvent some of the patriarchal regulation of their bodies. [6]

When we think through Sahrawi gender roles, and how women might liberate themselves from patriarchy, we cannot assume that gender roles function in the same way as they do in our own cultures. We must always work to undo the assumptions that stem from our subject positions, especially when we look to analyze other cultures from a Western perspective that have been historically understood through Eurocentric worldviews. Feminist Lila Abu-Lughod makes a similar argument in her book, Do Muslim Women Need Saving?, demonstrating that the Western desire to unveil Muslim women merely reduces all Muslim women to the veil without recognizing their individual humanity.[7] So while Sahrawi women certainly face oppression due to social media gossip, and patriarchal leadership within the refugee camps themselves, we need to particularize their position within Sahrawi gender roles. For example, we need to also account for how gender roles have provided Sahrawi women with a great deal of power within the family structure, the primary space for generating political alliances within Sahrawi culture.[8] These multiple narratives surrounding Sahrawi gender roles should be brought into tension with one another: the power that women have within the culture, the violence they face when others regulate their bodies through gossip, and the patriarchal leadership within the refugee camps.

This tension is on full display in the documentary. Near the middle of the film, Inma visits the Smara refugee camp town hall where she discusses with male leaders the value of sports to educate people. They welcome her into the community and say she will make a fantastic “ambassador” for the Sahrawi cause. They finish this encounter by presenting her with a certificate of honor, dress her up in a mefhla headscarf, a traditional garment worn by women, and take a picture with her. This is clearly a performance of gender for the camera. The Sahrawi men want Inma to be their ambassador—they accept her into the community—but she becomes a gendered ambassador. I will not attempt to guess how Inma felt about this encounter, but her facial expressions appear neutral to negative rather than overwhelmingly positive. This seems to suggest that this is a moment of conflict for her. On the one hand, it is excellent that the Sahrawis embrace her as one of them, but on the other hand, they also force a gender role upon her. This gender role does not take into account Inma’s lived experience as a Spanish-Sahrawi woman who has lived in multiple non-Sahrawi spaces.

The conflict comes to a head a few scenes later when Inma and Girouard have a heart-to-heart ‘off camera.’ Girouard puts the camera down but doesn’t turn it off. She points it sideways towards Inma from the floor while Inma describes how much pressure she feels to perform in certain ways. The low-angle shot is dark and disorienting, mirroring the confusion that Inma herself seems to feel. She describes how people are talking on social media about her and her birth mother, saying, “no Sahrawi woman would ever look like that,” and how a lot of people don’t approve of her mother “having been with a Spanish man.” She continues: “I never claimed to be Sahrawi, but it is part of who I am and it hurts hearing that.” Here we see the harm of gendered expectations. Inma has fully embraced her Sahrawi history, and so when a part of the community rejects her simply because she does not conform to traditional gender roles, this hurts her. This confusion that she feels over belonging or not belonging even makes her question her own gender within the Western Sahara. She says, “If I belong as anything, I belong as a man in this country.” Gender becomes confused because of a clash of cultural values. Inma has grown up as a woman within the Western world, which does not cohere with womanhood in Sahrawi culture. She exists in a liminal space between cultures, which has led some conservative Sahrawis to reject her. The scene ends with Inma wishing she could leave the Western Sahara: “I want this trip to be over.”

But this is not where the journey ends. The camera immediately cuts to a wide-angle shot of the beautiful Sahara Desert, followed by clips from a birthday party where everyone (including Inma) is smiling and laughing. There is still joy and love to be had in this journey. Soon after, Inma finishes the race, winning in the female category. She is told that this is the first year that two Sahrawis have won. Overcome with pride for her nation, she searches for a Western Sahara flag that she can take to the podium. She finds one but is still plagued with doubt as to whether she can wear it. She asks, “Who am I to call myself Sahrawi? I have been here for three days.” Then she meets a young boy, who she talks to about her conflicting histories. She asks him if he would like to see her bring the flag up on stage, if that is a good idea. He instantly responds with “Of course you should.” This is a moment of recognition from a stranger who is not her host family or part of the Polisario Front’s administration who want to use Inma for political means. It is a moment of pure acceptance. She is recognized as Sahrawi even though she does not conform to Sahrawi gender roles.

The camera pans away from Inmaculada Zanoguera Garcias to reveal the children playing in the tent around her.

Running Home is a magnificent snapshot of Sahrawi humanity. Michelle-Andrea Girouard brilliantly captures the feeling of the Sahrawi nation and broader diaspora community. Although the narrative focuses on Inma Zanoguera Garcias’ struggles with conflicting histories, the film’s parting message is not one of individual becoming. In the final five minutes of this thirty-minute film, Inma remarks, “People here have shown me a part of humanity that I had never seen before and that has nothing to do with me […] What a wonderful realization to come looking for something that you thought was about you and finding out that it’s not.” The camera then pans away from Inma to show a collection of children playing and laughing. This panning reveals the film’s collective nature. Certainly, this film is about Inma’s efforts to reconcile gendered Western and Sahrawi subject positions. Here, she fits herself within transnational feminist discourses that center women’s experiences of patriarchal power structures. But, it is also, quite simply, a story about human rights. It is a plea to hear the collective Sahrawi voices in a world that drowns them out, to listen to their humanity and do something to relieve their suffering.

You can watch the film here: https://www.runninghomedoc.com/

_____________________________

[1] Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the Subaltern Speak? In C. Nelson & L. Grossberg (Eds.), Marxism and the interpretation of culture (pp. 271–313). University of Illinois Press.

[2] Lippard, C. (2020). Mobilities in Cinematic Identity in the Western Sahara. In Cinema of the Arab World: Contermporary Directions in Theory and Practice (pp. 147–200). Palgrave Macmillan.

[3] Inma now lives in New York City, where she is a PhD student at The Graduate Center, City University of New York.

[4] Isidoros, K. (2017). Unveiling the Colonial Gaze: Sahrawi Women in Nascent Nation-state Formation in the Western Sahara. Interventions, 19(4), 487–506.

[5] Barona, C., & Dickens-Gavito, J. (2017). Memory and Resistance: A Historical Account of the First “Intifadas” and Civil Organizations in the Territory of Western Sahara. In Global, Regional and Local Dimensions of Western Sahara’s Protracted Decolonization: When a Conflict Gets Old (pp. 259-275). Palgrave Macmillan.

[6] Almenara-Niebla, S., & Ascanio-Sánchez, C. (2020). Connected Sahrawi refugee diaspora in Spain: Gender, social media and digital transnational gossip. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 23(5), 768–783.

[7] Abu-Lughod, L. (2013). Do Muslim Women Need Saving? Harvard University Press.

[8] Isidoros, K. (2017). The View from Tindouf: Western Saharan Women and the Calculation of Autochthony. In Global, Regional and Local Dimensions of Western Sahara’s Protracted Decolonization: When a Conflict Gets Old (pp. 295–311). Palgrave Macmillan.