by Moustafa Bayoumi

“It’s funny!” the hotel manager in the brown suit said to me while laughing. I had been staying in downtown Cairo, steps away from Tahrir Square, for the last five days and the manager was describing the street battles occurring right outside my hotel since the day I had arrived. He started talking about the futility of the fight. For hour upon hour, Egyptian kids, many of them barely teenagers, would throw stones at riot police who were down the street. The kids would then creep and inch forward. The riot police, not much older than the protesters really, would back up until feeling cornered and then lob tear gas projectiles and stones at the kids, who would then scatter and regroup. Then it would start all over again. They looked like two teams playing a sometimes deadly game of Red Rover. There have been hundreds of injuries, and at least three deaths nationwide since this latest round of protests began.

The day I arrived in Cairo, Mohammed Morsi, Egyptian’s first democratically elected president, had issued some very undemocratic decrees, the most extreme of which was that his past and future decisions would be above any sort of judicial review until the election of a new a parliament. In fact, Morsi didn’t even announce his extraordinary power grab himself, leaving that to a spokesman. Nor, it seems, did he tell all of his advisors. Samir Marcos, the only Christian on Morsi’s seventeen-member advisory team, resigned in protest, saying he hadn’t been consulted and that he learned about the decrees from television. The posture of the president—the paternalism, the consolidation of power through “temporary” measures, the overreach, the unaccountability—all looked too familiar to many Egyptians. Thousands came to Tahrir to protest, and people started calling the President Mohamed Morsi “Mubarak.” One magazine had a picture of Morsi looking into a full length mirror, and Mubarak looking back at him as his reflection.

It was noon at the Shepheard Hotel when the manager and I were having our conversation, but you would never have known the time. For the last few days, metal gates had been covering the windows, so guests ate their omelets and fuul breakfasts in a kind of post-apocalyptic darkness. The front door had been sealed shut as well. To leave, you had to go through a back door, down a flight of stairs, past the laundry collection and into the garage. This back entrance let you out on an alleyway that opened on one side to the Nile and on the other to a barricaded entrance of the American Embassy, where a small, hapless group of policemen stood behind razor wire up to eye level. I was checking out of the hotel on this day, and asked the manager if I could come by later to pick up my luggage. Suddenly, his smile vanished. “At what time?’ he asked me. I said I’d be back between 6 and 7 pm. “But not later,” he said, making me promise. The battles had been escalating over the last few days, and today a major march to Tahrir had been called. “We will close the hotel at 9 pm.”

I had come to Cairo to deliver two lectures at the Center for American Studies and Research at the American University in Cairo. The city is also where my mother was born. She grew up on Qasr el-Aini Street, just down the street from my hotel. This is one of the majestic and grand boulevards of Cairo that has now been reduced to rubble and the odd “car-be-que,” vehicles set aflame and burned into skeletons of steel, usually by Molotov-cocktail throwing youth. The site of violent confrontations a few days ago, the street is now walled off by concrete blocks.

AUC and I had made arrangements months before, when Tahrir had been relatively calm. But in the last few days, the square and certain areas around it had come back to revolutionary life. Mohamed Mahmoud Street, just off the square, had exploded days before I arrived in Cairo, as the young people wanted to commemorate their losses from deadly battles with the police on that street the year before, and then Morsi’s decree brought many more young people out to battle the riot police. They concentrated their fights on the area around my hotel.

The Shepheard Hotel brags that it was originally built on the site that Napolean used as his headquarters when the French invaded Egypt in 1789. It was rebuilt in its current location after being burned down in the unrest leading up to Egypt’s 1952 revolution, and today, it’s essentially beside the American embassy. It’s also almost in front of Simon Bolivar Square, the main area where the current street battles are happening.

On my second night in Cairo, I returned to the hotel after having dinner with my cousin and his family. As I approached the hotel, I suddenly realized that there were a lot of young men in kufiyyehs and with rocks in their hands standing outside the hotel door. I stopped to observe the fights when a tear gas canister landed about fifteen feet away. It felt like a colony of caterpillars had invaded my throat and nose. Breathing became difficult long before tears came to my eyes. By the time I made it back in to the hotel, an armored police van had pulled up at the end of the street in an effort, it seemed to me, to block and corner the stone-throwing youth and trap them on the small street. Instead, they attacked the vehicle fearlessly. Some ten minutes later, it was on fire.

The young men throwing rocks at the police are not drawn to this area because of the American Embassy. They are drawn to the area because there are police there to scuffle with (and the police are there because of the American embassy). The fact that this little square just off of Tahrir is named after El Libertador Simon Bolivar, that the American embassy squats right there (it’s a concrete behemoth of a building), that until these latest battles the square also had a protest tent by supporters demanding the release of Sheikh Omar Abdul Rahman from a US prison, and that it is almost flanked by a mosque and a church, shows how layered geography in Cairo is and how quickly the geography becomes newly symbolic in revolutionary times. Everyone now talks about Midan Simon (Simon Square), and the youth even put a surgical mask on the liberator’s statue, turning him into a Cairo revolutionary.

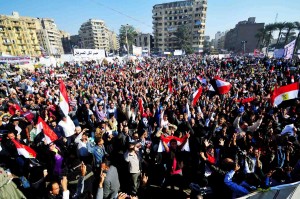

Simon Bolivar Square is newly important, but Tahrir is still the grand symbol of politics in Egypt. The left, liberal, and independent parties have set up camp since Morsi’s decree. A tent city is there, reminiscent of the 18 days that brought down Mubarak in 2011, though everything’s more difficult now, for sure. The country was almost completely united in its hatred of the old regime back then. Now it’s significantly divided. Meanwhile, the political institutions of the society are either non-functioning, deeply suspicious or each other, or at each other’s throats. In this environment, holding the square is what matters, and we may be seeing a rare moment when the left, liberals, and independents are unifying to challenge the right-wing religious parties. The Muslim Brotherhood understands this and had called for their own “millioniyya” or million-man march to happen on Saturday, December 1 at Tahrir Square, already occupied by the opposition. Chances of a bloodbath, and a bloodbath between fellow Egyptians, and not between police and protestors as had been typical, increased immediately. Brotherhood members appeared on TV talk shows arguing about the importance of seeing Morsi supporters in Tahrir to show the nation that he too has more than enough support to fill the square.

People started preparing themselves mentally. Talk of another “Battle of the Camel” scenario, when Mubarak supporters fought revolutionaries in the square and on camels and horses during the 2011 revolution floated everywhere. Others shook shaking their heads in disbelief at the stupidity of Brotherhood’s idea, and many wondered if the military, so far absent from view, would appear on the square. The next day, the Muslim Brotherhood announced a change in the location of their march, “to protect Egypt’s national interests against division and conflict,” they said. They will march now outside of Cairo University, in Giza.

Tahrir, for now, still belongs to the liberals. But the fact that the Muslim Brotherhood felt it had to march to Tahrir at all shows how, in these drawn-out revolutionary times, when the country is basically without any real and accountable institutions of governance, the ability to hold, to name, and to shape the symbolic message of urban geography is what matters. As the contests over the shape of Egypt divide more starkly between different parties and visions, the debates will continue to fill up the endless talk shows on Egyptian television, but it’s still that patch of concrete that counts. After the fall of a regime, military rule, formation of political parties, multiple elections, dissolution of parliament, and more, the fact remains that the most recognized path to political legitimacy in Egypt today is still the same: Occupy Tahrir.