MELISSA PHRUKSACHART

The experience of Kara Walker’s exhibition “A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby” begins in the palm of one’s hand. Publicity photos of the great sphinx had been disseminated online long before the installation opened on 10 May. Photography was openly encouraged at the exhibit, and people were invited to share their photos online with the hashtag #karawalkerdomino. The organization that commissioned the work, Creative Time, now features a “Digital Sugar Baby” on its website consisting of these crowdsourced images of the sphinx, indexed anatomically. This juxtaposition between the work’s incessant digital mediation by visitors and its suggested meaning – a comment on the “sugarcoating,” in Walker’s words, of the violences of American history – is what gives A Subtlety its secret force.

Upon entering the Domino Sugar Factory, viewers were unapologetically primed about the social, historical, and political stakes of the work through Walker’s longer subtitle, “an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant.” This grandly signaled the factory ground as the site of mediation between “our sweet tastes” and enslaved black bodies purposely positioned as Other. Walker asserts that these “unpaid and overworked artisans” (she does not call them laborers, or even enslaved, archly insisting upon the skill and value they transmitted into their work) “refined” our tastes as they did our sugar, the two being directly tied. As any reader of the Little House on the Prairie series can tell you, processed white sugar was more expensive and reserved for when guests came, while cruder forms of brown sugar and molasses were for everyday use. The title also flags the multiple forms of “artisanal” work involved here – physical labor in the cane fields and culinary and affective labor in American kitchens. Through this eloquent phrase, Walker succinctly mourns and honors her subjects. Cleverly, she leaves viewers to do with this as they will.

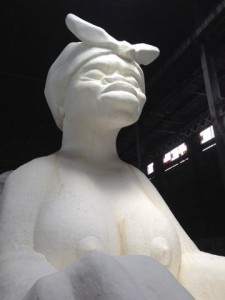

Before reaching the base of the thirty-five-and-a-half-foot high mammy-sphinx encrusted in white sugar, the spectator walked through the exhibition space and around life-sized statues of black children – pickaninnies – hauling baskets of sugar. While the sphinx is pure white, the boys are dark brown, made of a resin that resembles hardened molasses (curiously, there are no ants). The properties of the material are such that these young attendants slowly decomposed over time; when I visited on 28June, many had already smashed to the floor. These were of great interest to visitors, who eagerly took photos of – but rarely with – them. At life size, they perhaps seemed too real, too innocent, although Walker says she based them on some “goofy” figurines she bought on Amazon.

On the contrary, it was not the case with the marvelous sugar baby. It seemed that nearly everyone who passed through stopped for a photo in front of the sphinx, most calmly smiled, the same way you might when posing in front of the hundreds of attractions that dot the city. Others invariably took the bait and posed so as to be captured playing with the sphinx’s breasts or pudendum while others laughed. (See Stephanye Watt’s “The Audacity of No Chill: Kara Walker in the Instagram Capital” in Gawker or Nicholas Powers’ “Why I Yelled at the Kara Walker Exhibit” in the 30 June digital edition of The Indypendent). Although I dislike such reactions, I think Walker anticipated this response, understanding this piece not just as a sacred monument to the past, but also as a vicious mirror of the present.

Undoubtedly, A Subtlety generates meaning not only through the observation of the objects assembled, but through the way in which the audience interacted with it. While sexual degradation of the mammy-sphinx was one noxious response to the piece, most folks did not engage with it this way. As I said, they smiled, they posed with their children. For most, the camera rendered the sphinx both distant and intimate. For instance, one could see photographers on the lookout for a worthy angle or cool shot of a pool of resin next to the broken head of a child.

It is worth noticing that the piecemeal aestheticization of these laboring bodies was puzzling. The crowd on the day I attended was, for a New York City art event, unusually diverse in age, race, and class, a result of the exhibit’s free admission, provocative form and subject matter, and heavy publicity. Clearly, many sections of the city (and beyond) were drawn to something A Subtlety promised to offer: resolution? tribute? education? mere spectacle? I tried to eavesdrop on conversations, but most seemed cheery and superficial: “If I said lunch, would anybody object?”

What does it mean that A Subtlety became, for some, a space of joy and relaxation? Indeed, a healthy dose of children numbered along the attendees. It’s not that this exhibit was not suitable for children, but I did wonder what these nouveau Brooklyn parents thought their children would get out of attending. The kids mostly scampered around the large, open warehouse, unaffected by the decaying child-figures around them. The memory of three smiling white girls in their summer play dresses, posing for a photo in front of the sphinx’s left flank, still gnaws at me.

But I’m not trying to ultimately argue that the installation should have produced “proper” affective responses; nor do I want to claim that I read everyone’s minds and concluded that no one apprehended the piece correctly. I also don’t want to make the case that photography is in and of itself an alienating medium (hello, Walter Benjamin). Rather, this work was not just about representing in a new way its purported subject matter, it also raised questions about what we do with the opportunity to experience such a confrontation with “history.” Several groups took this conversation even further. An ad hoc event, “The Kara Walker Experience: WE ARE HERE,” urged people of color to gather at the exhibit on 22 June “so that we can experience this space as the majority.” “Subtleties of Resistance,” which took place on 5 July, crowd sourced a series of critical dialogues and performances around Walker’s themes inside the Domino.

Nato Thompson’s curatorial statement for Creative Time summarized: “Walker’s gigantic temporary sugar-sculpture speaks of power, race, bodies, women, sexuality, slavery, sugar refining, sugar consumption, wealth inequity, and industrial might that uses the human body to get what it needs no matter the cost to life and limb.” Yet, what Thompson misunderstands is that this is not the point of Walker’s work, it’s merely its point of departure. What A Subtlety made tangible were the perverse desires with which people want to see these themes brought to life again and again, merged with the eerie nonchalance they leave behind once they’ve Instagrammed it. A Subtlety is not merely an intellectual prompt, it is a moral challenge.

I have noticed you don’t monetize gcadvocate.com, don’t waste your traffic, you can earn extra cash every month with new monetization method.

This is the best adsense alternative for any type of website (they approve all

websites), for more details simply search in gooogle: murgrabia’s tools