HILLEL BRODER

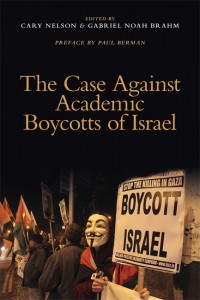

Recent anthology arguing against the academic boycott of Israel edited by Cary Nelson and Gabriel Brahm, with essays by scholars from Britain, Israel, and the United States.

Certainly, scholar activism (and activist scholarship) has a long history among faculty and students at the City University of New York. In his last editorial Gordon Barnes, The Advocate’s editor-in-chief, reminded us of the scholarly imperative to act politically:

“It is impossible to divorce our individual selves, or our collective selves from politics. Our scholarship is often politically influenced or derives from a particular set of experiences that involve political thought, this is particularly true for those of us in the social sciences and humanities.”

The question of politics in the academy and academic action within the political is a central one to this institution, its scholars, and its publications. At The Advocate, for example, we’ve come to expect the regular exposure of institutional abuse and exploitation of its contingent labor, and as contingent labor, we’ve benefited from the voice that publications such as these offers adjunct advocacy projects. If anything, The Advocate strives to realize itself as a forum for the oppressed in proliferating the generative and transformative roles scholars might hold.

However, when it has come to advocating for and enacting a political stance in solidarity with Palestine, these pages, as well as various other forums for student political engagement, have nearly taken for granted—and normalized—the reigning rhetoric of the Boycott, Divest, and Sanction (BDS) movement against Israel without a critical examination of the history and vision of BDS, the premises of BDS, the allies of BDS, alternatives to BDS, and the effects of BDS both on our institution and in the world.

It was hardly surprising, therefore, that such dominant rhetoric at CUNY culminated in an attempted vote to boycott academic institutions in Israel, put before the DSC plenary session, just last month, on 24 October. The Advocate’s consistent angle certainly suggested moving towards such a resolution; in Barnes’ own words following the DSC plenary, such an emphasis on rigorously pointed political advocacy is understandable, even as The Advocate accepts contributions from students of all political persuasions.

However, the loudest voices about BDS were not reflective of popularly held opinion here at the GC. For it was also not surprising that this resolution was met with enough resistance—or at least enough ambivalence—by representatives and their constituents that it did not pass. In the democratic process over the course of the plenary, opposed doctoral representatives and students expressed various arguments, reiterating those discussed at prior department meetings and on various departmental email listservs, and these arguments proved strong enough to divide the vote to a sufficient degree.

The purpose, in what follows, is not solely to recap or reconsider what has been argued about the failed DSC resolution. Instead, I discuss a range of narratives around the question of Israeli-Palestinian relations and futures that call into question the necessarily absolute nature of an academic boycott of Israel. I suggest that we rethink the matter not by normalizing relations per se, but by holding in tension various discourses about the geo-political crisis in question, while scrutinizing the performance of reactive politics in both our local and global spheres. Throughout, I cite articles from the very recently published collection of scholarly articles The Case Against the Academic Boycotts of Israel.

However, in order to move forward, I first look back by summarizing the reigning rhetoric around BDS thus far at CUNY (and, to some degree, elsewhere), even as I risk simplifying the rhetorical history and historical evolution of the movement.

The resolution, as all such resolutions to boycott Israel, invokes a response to “Palestinian Civil Society” (PCS) which has issued an international call for BDS against Israel until Israel, according to PCS, ends its occupation of Arab lands, recognizes equal rights for the Palestinian citizens of Israel, and promotes the right of return of Palestinian refugees. As academics, a group of doctoral students at CUNY responded to this call by considering a resolution to boycott academic institutions in Israel and divest from Israeli companies. In so doing, BDS proponents claimed to demonstrate solidarity with oppressed Palestinian academics, as well as followed the precedent set by a few United States academic bodies, including the American Studies Association (ASA). Anticipating an onslaught of criticism, students argued along the way that such a resolution is anti-Zionist but not anti-Semitic; additionally, students argued that such a boycott supports the academic freedom of Palestinians while not suppressing the academic freedom of individual Israeli scholars—only academic institutions, they claim, are complicit with “apartheid”-like military action.

Certainly as academics and empathic humans, CUNY students stand in solidarity with the suffering of the Palestinian people and the decades-long travail that Palestinian academics have suffered to maintain their profession and practice in a controlled and contained authority and non-state. We are at once deeply connected to and moved by such suffering, yet we feel powerless unless we respond to a call to action. And this is where we should think about political action in a nuanced way, as well as consider the outcomes of the proposed BDS program, of which the proposed but defeated DSC resolution to boycott academic institutions in Israel was but a part. How do we respond, in fact, when the Israeli university system not only maintains the most liberal institution for academic freedom and political resistance in the country—and in the Middle East? How do we make sense of the hundreds of institutionally-backed partnerships between Israeli and Palestinian scholars? And how do we proceed, too, with the knowledge that Israeli universities are at once democratic and non-discriminatory, encouraging the attendance of a diverse student body of Palestinian, Arab, Christian, Muslim, and Jewish students? In this regard, how, in fact, do we reconcile the call to boycott Israeli academic institutions when Omar Barghouti, the spokesperson for the BDS movement, studied for his doctorate from Tel-Aviv University, the institution that guarantees his academic freedom? How do we make sense, in fact, of the academic freedom afforded to all of the resisters and reformers of the political state of Israel, including Neve Gordon, of Ben Gurion University, an outspoken proponent of the BDS movement? And how do we parse the most immediate effects of the ASA boycott as affecting a Palestinian student at Tel Aviv University, who was unable to recruit outside readers to review his thesis due to the boycott?

The first step towards a different narrative is to establish a future in which Israel, as a country, exists, as well as recommending political action with the future of Palestinian citizens living alongside Israeli citizens in two independent countries. This is opposed, of course, to the reigning BDS rhetoric—and implicit BDS subtext—in which a state of Israel would be dissolved to allow for a unitary state. Indeed, the third plank of the BDS movement, the right of return for all refugees (and their descendants, forever), is an untenable solution for Israel to accept and a politically divergent solution in global politics—denying, much as Peter Beinart has shown in his argument against the ASA boycott, the viability for an independent, democratic, Jewish state alongside a Palestinian one.

And CUNY’s Beinart is not alone. Indeed, Palestinian Prime Minister Mahmoud Abbas, the Palestinian Authority, and the Middle East quartet only see a two-state solution as the possible end-game for the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict. At Nelson Mandela’s funeral, for example, Abbas drew a distinction between boycotting Israel and boycotting the territories—the former of which he adamantly did not support for the economic and political welfare of his people (Beinart has made a similarly nuanced argument). In so doing, Abbas distinguished himself from extreme elements such as Hamas, the reigning power in Gaza that calls for Israel’s annihilation in its charter. And in so doing, Abbas distances himself from the reigning rhetoric of the BDS movement that calls for an effective dissolution of the state of Israel. Gabriel Noah Brahm and Asaf Romirowsky argue as much in their important article about BDS, “Anti-Semitic in Intent If Not in Effect”: The BDS insistence on a “territory stretching from the river to the sea” is “the antithesis of a call for peace and reconciliation between two peoples in a compromise solution that would allow both a place in the sun, side by side, in some kind of harmony.”

Such words echo those of an early, joint statement by the presidents of Al-Quds University and Hebrew University in 2005 in response to calls for an academic boycott. Both presidents argue that the functional site—and cultural beneficence—of the university generates constructive, collaborative political action:

“Bridging political gulfs – rather than widening them… –between nations and individuals thus becomes an educational duty as well as a functional necessity, requiring exchange and dialogue rather than confrontation and antagonism. Our disaffection with, and condemnation of acts of academic boycotts and discrimination against scholars and institutions, is predicated on the principles of academic freedom, human rights, and equality between nations and among individuals.”

This past January, a professor from Al-Quds was interviewed by the New York Times about the international movement to boycott Israel; on the condition of anonymity, this professor attested that:

“More than 50 Palestinian professors were engaged in joint research projects with Israeli universities, funded by international agencies like the U.S. Agency for International Development. He said that, without those grants, Palestinian academic research would collapse because ‘not a single dollar’ was available from other places. He rejected the call for a boycott as having no practical value.”

Even more: while proponents of an academic boycott claim to uphold academic freedom in solely focusing on Israeli institutions and not individuals, such a claim offers a false distinction that fails to reflect the practice of scholarship and the particular economy unique to academic freedom. These institutions, they claim, are complicit in militarized aggression, either explicitly or tacitly, in their governmental funding and affiliation. Again, I wonder if there’s an exclusivity to which Israel is falsely held—do not all nations fund their universities and benefit from research conducted at said institutions? At CUNY, we are not necessarily complicit with the agendas of our host institutions that guarantee our right to practice scholarship freely, but we are also not free to practice scholarship independently. To suggest that academic freedom exists independent of institutional affiliation and support is to imagine scholarship as a neo-liberal enterprise in which independent scholars operate independent of institutional funding and protection. Indeed, we are scholars with institutional affiliations, much as our counterparts in Israel—not by choice, but by necessity. We need universities to fund our studies, teaching, and research and to ensure and protect our academic freedom.

And that might be the best way to appreciate that academic freedom is an absolute priority. As scholars, we must recognize that scholarship at its best is based on the merit of ideas, not their nationality. We don’t trade in the economy of ideas; if anything, we critique such economies by enabling the optimal exchange of ideas. But we are bound by our nationality and institutional affiliation to the extent that they make such critique possible.

Unfortunately, encouraging a divisive, exclusive narrative—both in conferring rights of academic freedom upon some while excluding others—perpetuates the greater BDS narrative in which Israel is the villain and aggressor and Palestine is the oppressed and colonized victim, which in turn freezes and reverses diplomatic progress by justifying the political right in Israel, on the one hand, and absolving the terrorist cells in Palestine, on the other. When two young Palestinian men commit a horrific massacre of four rabbis at prayer in a West Jerusalem synagogue, as occurred (as of this writing) just last week, the aggressors are lionized by Palestinian media and officials as both heroic soldiers and agent-less victims, and the victims, four praying rabbis, as colonizing occupiers whose deaths are simply the collateral damage of Israel’s occupation. Let us be clear: these four rabbis were not occupiers of disputed territory, nor were they soldiers of any sort. They were four rabbinic scholars who were victims of a “brutal, ideological murder”; and they were killed solely because they were religious Jews living in the land of Israel and attending a house of worship. Yet Hamas and other Palestinian leaders would have you believe otherwise. While Mahmoud Abbas, the Palestinian Authority Prime Minister condemned this recent attack in no uncertain terms, Hamas celebrated in the streets, lauding these two axe-murderers as heroes and holy martyrs.

This particular attack, unfortunately, has been described by many, including various Arab media outlets, as the turning point towards a “third intifada”: it is, at once, a horrific, culminating moment in a recent spate of terror attacks on Israeli civilians (at least two Palestinian terrorists have slammed their cars into crowds at train stations, indiscriminately killing civilians, in the past month—and, in a terrible coincidence, only days before and days following the failed DSC vote to sanction Israel!). Some have even accused Abbas of inciting such hatred in his response to what was a “call for freedom of prayer at the Temple Mount” for people of all faiths by a victim of a recent assassination attempt, Rabbi Yehuda Glick; while Netanyahu has vociferously denied such an attempt, the Arab media has spun such conciliatory and pluralistic rhetoric into a conspiracy by Israel to take over the Haram al-Sharif, which in turn has compounded the call for not only active resistance but terroristic action—and in the case of the four murdered rabbis, against Jews praying in their own houses of worship. The fine line between “active resistance” and absolute terrorism and violence is fine indeed—and one must hope that the absolutely devastating features of an “official” intifada are averted, if only for their divisive dead-ends.

All of this is to say, of course, that Israel and Palestine are future nation-partners, and that identifying Hamas, the reigning government in Gaza and an internationally recognized terror organization, as an enemy of both peoples and their futures is to identify the tacit and terrorist allies of BDS ambitions. Of course, not all who protest Israel’s occupation would wish Israel into the sea. This is only to say, then, that we rethink the implications of a divisive, destructive politics, and the international parallels of such resistance. We should ask ourselves about the endgame in considering such proposals: Is BDS actually suggesting a political future for Israel and Palestine to live side by side? Or does it further alienate the two sides from one another and empower the common enemy of both, Hamas, to resist with violence and terrorism against its own Palestinian people (aside from terrorizing the entire Israeli population), while it seeks to destroy PCS in the name of “liberation” by filling the vacuum (as it has done in Gaza)?

Think, for example, about the most recent war in Gaza this past summer, a war for which the DSC resolution condemned Israel entirely but ignored Hamas’s presence and actions as morally reprehensible—and of provoking war. Indeed, while Israel absorbed aggressive and indiscriminate rocket and missile fire across its borders with Gaza, “Israel went to extraordinary lengths to limit civilian casualties” in its counter-attack against Hamas terrorists, Joint Chiefs Chairman General Martin Dempsey stated this past month, through an elaborate warning system and targeted air-strikes. In villianizing Israel as the sole regional aggressor, BDS proponents somehow forget the daily existential threat to Israel’s citizens from the highly militarized, terrorist-ruled and Iranian-funded Hamas controlled Gaza strip. Given Israel’s right to exist and maintain secure borders, Israel has the right to defend itself from the absurdly frequent rocket fire that terrorizes and traumatizes Israel’s south on a daily basis. As Amos Oz was quoted, in a recent New Yorker article reassessing the genocidal threat against Israel’s citizens, “What would you do if your neighbor across the street sits down on the balcony, puts his little boy on his lap, and starts shooting machine-gun fire into your nursery?” If you fire back, are you guilty, in fact, of genocide – or of self-preservation?

To claim that Israel has the right to exist is not to claim a form of racism against Palestinians, nor is it to propose an exclusive Zionism. It is simply to affirm an internationally recognized state’s right for self-determination. But to claim that Israel does not have a right to exist is certainly anti-Zionist, if not anti-Semitic. Indeed, while certain pockets of boycott proponents have drawn fine lines between anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism, popular discourse and action against Israel’s supporters trends quickly into the anti-Semitic. The action this past year in Paris and Berlin by pro-Palestinian—and anti-Semitic—mobs evidenced as much in their targeting of Jewish businesses, synagogues, and individuals. And in the United States, Jews at colleges across the nation report being terrorized by Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) activists, including at CUNY’s John Jay College, at which students were singled out by SJP protesters as Jews. Students at Temple University have reported being called kikes by SJP protesters in protests that are, supposedly, only anti-Israel. . And yes, counter to others’ evidence in these pages that BDS is not anti-Semitic in pointing to the Jewish supporters of BDS, I would only counter by suggesting, as many have shown, that “Jew washing” is not evidence enough—indeed, plenty of Jews can be amply anti-Semitic. I heard as much at the 24 October DSC Plenary, at which one student suggested that BDS’s sole value for CUNY students is to “tell the power structure of the Jewish establishment that they’ve lost their own turf”, as the DSC resolution would “have no direct effect on Israeli institutions, let alone Palestinian self-determination.” If the purpose of the symbolic gesture of BDS is reflexively directed upon our own power structures—and the goal is focused entirely on the Jewish establishment and Jewish politics—then what is exposed is an internal and specifically Jewish critique.

Furthermore, in considering the history of all boycotts, liberal intellectual Paul Berman has argued that the boycott of Israel is, perhaps, the oldest and most pliable of boycotts, one in which its proponents are constantly grappling with the terms of its merit—and in which its adherents find it impossible to disentangle its current rhetoric from echoes and rhetorical parallels of anti-Semitic discourse. Why, in fact, is Israel, a secular, democratic, and inclusive state, the only state in which Muslims, Christians, and Jews are free to worship alongside one another, the only one state that guarantees equal rights to women and ethnic groups and gays, the subject of sanctions? If the intention is to sanction all human rights violators and violations, and the only action taken is to sanction the Jewish state, then one must wonder about the underlying intentions—and the lack of recourse for a historically oppressed people in the call for its national dissolution. As Emily Budick writes, with the objection to the establishment of a Jewish state in 1948, of “returning to their national homeland after millennia of persecution and the Holocaust, there can be for BDS only one reasonable solution: the dissolution of the State of Israel.” To support Israel, in other words, is not to support Zionism in any form. It is simply to adopt a reasonable position of anti-anti-Zionism in our current political climate, much as Ellen Willis has suggested, in her 2003 essay “Is There Still a Jewish Question?” Willis writes that the “logic of anti-Zionism in the present political context entails an unprecedented demand for an existing state—one, moreover, with popular legitimacy and a democratically elected government—not simply to change its policies but to disappear.” Certainly the ASA President seemed to fall short of reason and even implicates his own motives when responding, in response to New York Magazine’s Jonathan Chait, that “many of Israel’s neighbors are generally judged to have human rights records that are worse than Israel’s [but] one has to start somewhere.” Starting somewhere, in this instance, involves nothing less than an endgame in which Israel disappears.

We’ve reached a stalemate, then, if the descent abroad results in a divisively absolute, supposedly agent-less, and entirely anarchist agenda, and the descent locally into anti-Semitic discourse and action. We recognize as scholars, too, that scholarship has its own economy of ideas, and that nationalist affiliation is at once necessary and irrelevant. As scholars considering this particular historical impasse, then, how might we build a discourse at universities that tolerates difference, that advocates two nation-states, and that does so in a mutually respectful—even if non-normalizing—manner? How, in other words, might we counter the absolutist “solution” of Hamas-fueled, genocidal rhetoric of “liberation” from the “river to the sea”? How might we counter, in Sabah A. Salih’s words that Islamism that has found “intellectual colonization” and safe-haven within the Left by way of an unquestionable reification—and distortion—of Said’s Orientalism? How might we reawaken our critical sensibilities to the shock that Martin Amis articulated in 2006 upon returning to England and witnessing placards at anti-Israel protests pronouncing ‘We are all Hezbollah Now?’

I wonder. Instead of moving towards more incendiary rhetoric, what if we were to resolve today, instead, to host a conference of Palestinian and Israeli scholars on questions of narrative and history? What if we, as models of rhetorical culture and engagement, imagined and worked towards a world in which both narratives and histories would be legitimized, even if held in a productive and irreconcilable tension? Let’s be clear: narratives and histories may never be resolved, and fraught claims for contested sites should not be normalized. But such is the work of political practice: to move beyond the easy performance of absolutist politics, we must sustain a model for collaboration and constructive inquiry—and what better place than our own Graduate Center to host such a conference. We might look at Shira Wolosky’s classroom, self-described in her essay “Teaching in Transnational Israel,” as a model for conflicting rights not through denial of narratives’ rights or normalization of the status quo, but through addressing “responsibility and respect of difference”, by way of a Levinasian ethics of difference. Perhaps, too, we might seek models of past successes by examining the 2013 special issue of Israel Studies entitled “Shared Narratives,” which brought together the work of scholars from Israel and Palestine. I imagine that in such a tense political sphere, such action would certainly carry as much symbolic traction as the proposed, deleterious, failed boycott, and especially so in its resistance to the reigning conformism demanded by BDS absolutism.

Such productive ambiguity would be in good company with other academics fighting to retain academic freedom in a world in which institutions, regardless of their politics, promise such freedom to their academic constituents. Take the international petition to oppose boycotts of Israel’s academic institutions signed by over 1,500 academics: the petition prides itself in the core principles of an absolute academic freedom; the suspicion of mediated truth-claims; the global consensus for two, peaceful states; and the need for free access to world-wide and nation-less scholarship. Similarly, in response to the American Association of Anthropologists’ boycott of Israel, 300 anthropologists responded with a counter-petition on the grounds that “to boycott Israeli universities is a refusal to engage in productive dialogue…In Israel/Palestine as elsewhere, anthropologists can contribute by listening, learning, and leaving room for ambiguity.” Finally, in a rally against the proposed and failed attempt at a boycott here at the DSC, over 250 signers signed an online petition denouncing the resolution as anti-academic freedom and overly simplifying of a complex history. Ultimately, all petitions recognized, as Sari Nusseibeh, president of Al-Quds University in Jerusalem, has said, that “If we are to look at Israeli society, it is within the academic community that we’ve had the most progressive, pro-peace views and views that have come out in favor of seeing us as equals.”

As scholars of the humanities and sciences, then, let us follow the anthropologists’ call to “leave room for ambiguity.” Such is our training, responsibility, and legacy, as scholars, even as we engage in the practice of politics. As Michael Berube, the past president of the MLA wrote regarding the ASA resolution, the difference between the two organizations is that the former is a scholarly organization that is “firmly committed to the free and open exchange of ideas”, while the other “has other priorities.” In so doing at CUNY, we follow MLA’s precedent and continue to forbid absolutist, reductionist, privileged, and dangerously divisive positions.