Rhone Fraser

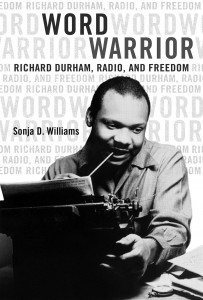

In her biography of Richard Durham called Word Warrior: Richard Durham, Radio and Freedom, Sonja D. Williams accomplishes her stated goal of “a book-length account about the totality of Durham’s contributions and advocacy.” Richard Durham (1917-1984) was an extraordinary journalist, dramatist, and speechwriter who used his skill of writing to challenge the racist assumptions of the U.S. hegemony controlling the film, radio, and television industries of the twentieth century. Durham’s writing reflects a reverence for historically-based research like none other. He was a paperboy for the Pittsburgh Courier, a writer for the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and the top investigative reporter for the Chicago Defender. In 1948, he produced the legendary radio drama series, Destination Freedom; was a writer for the NOI’s national newspaper, Muhammad Speaks; a collaborator with Muhammad Ali on his popular autobiography for Random House that Toni Morrison edited; and a speechwriter for the pioneering Chicago mayor, Harold Washington. His writing incorporates history in a creative way that appeals to mass audiences. Williams’ primary sources include in-depth interviews with artists like Oscar Brown Jr. In referring to Durham, Brown observes he “had been a leftist” and “Communist, who explained the intricacies of Marxism and Leninism to him.” Williams writes that for Durham, “Communist philosophy was more in line with the liberation of Negroes and other oppressed people than capitalism.” Throughout his life, it is clear that Durham sought to liberate Negroes by using historical fiction to translate their heroic stories. According to his brother Earl, Durham firmly believed that “if you want to fight injustice, you have to organize people to do it.”

In her biography of Richard Durham called Word Warrior: Richard Durham, Radio and Freedom, Sonja D. Williams accomplishes her stated goal of “a book-length account about the totality of Durham’s contributions and advocacy.” Richard Durham (1917-1984) was an extraordinary journalist, dramatist, and speechwriter who used his skill of writing to challenge the racist assumptions of the U.S. hegemony controlling the film, radio, and television industries of the twentieth century. Durham’s writing reflects a reverence for historically-based research like none other. He was a paperboy for the Pittsburgh Courier, a writer for the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and the top investigative reporter for the Chicago Defender. In 1948, he produced the legendary radio drama series, Destination Freedom; was a writer for the NOI’s national newspaper, Muhammad Speaks; a collaborator with Muhammad Ali on his popular autobiography for Random House that Toni Morrison edited; and a speechwriter for the pioneering Chicago mayor, Harold Washington. His writing incorporates history in a creative way that appeals to mass audiences. Williams’ primary sources include in-depth interviews with artists like Oscar Brown Jr. In referring to Durham, Brown observes he “had been a leftist” and “Communist, who explained the intricacies of Marxism and Leninism to him.” Williams writes that for Durham, “Communist philosophy was more in line with the liberation of Negroes and other oppressed people than capitalism.” Throughout his life, it is clear that Durham sought to liberate Negroes by using historical fiction to translate their heroic stories. According to his brother Earl, Durham firmly believed that “if you want to fight injustice, you have to organize people to do it.”

In 1923, when he turned six, Durham’s family migrated from Mississippi to the Bronzeville, Chicago. To supplement their income, he worked as a paperboy for the Pittsburgh Courier. Part of his literary diet included editorials written by W.E.B. Du Bois. Also fundamental was the story of Richard I, England’s twelfth century monarch to whom Durham took such a liking, so much that he started calling himself Richard in his teenage years despite his birth name being Isadore. King Richard was a brilliant military strategist, best known for his exploits during the so-called “Third Crusade.” This battle aimed to recapture the city of Jerusalem from Muslim control during the late 1100s. According to Williams, by the age of eighteen, Durham had access to Bronzeville’s first public library, and it became his “personal resource bank.” His brother Caldwell said that Durham read everything in the fiction section.

Williams presents Durham as supportive of the militant exploits he writes of in his interpretations of stories. Durham’s early review of Dale Carnegie’s book, How to Win Friends and Influence People, asserted that no “how-to” book could solve our social and business problems. He resisted the vision of industrialists like Carnegie throughout his life. He advocated for “Negro liberation” through his promotion of such “realistic paradigms.” He expressed these themes in poems that were published by the Chicago Defender and the New Masses periodicals. The publications included “Death in a Kitchenette,” which features a black, working protagonist, who was “cheated” out of two weeks’ rent by “pneumonia” and “death.” This captures Durham’s dramatization of the struggle to survive in an environment where jobs became increasingly scarce. At twenty-three, the Works Progress Administration’s (WPA’s) Illinois Writer’s Project hired him under bibliophile Arna Bontemps on a 1939 study called The Negro Press in Chicago. The small study examined thirty-four Black newspapers and eleven magazines from the city’s past and present. In this experience, Durham became critical not only of the living conditions of Black working people but also of the Black bourgeoisie’s support of it. While Negro presses, then, like the Chicago Bee praised Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal policies such as the WPA that hired Durham, once in these positions, Durham didn’t fulfill their expectations. He critiqued the process that saw overwhelming masses of Negro people denied gainful employment despite the tokenism of the industrialists and their supporters. “The economic position into which [Negroes] are forced makes a mockery of American democracy,” Durham insists. This job exposed Durham to radio writing. Once exposed to this genre and opportunity, Durham never left. He freelanced for the NBC radio drama series called The Lone Ranger. The series presented the story of a former Texas ranger who protected his countrymen in the untamed West of the late nineteenth century. Durham noticed the racist and sexist storylines in these scripts. Industrialists such as William Randolph Hearst, General Electric, RKO, Marconi Wireless and Telegraph, and Westinghouse heavily protected the scripts as they opposed original ideas threatening their rule. He probably learned from this experience how to convince industrialists and their functionaries to support his own original series that celebrated radical thinkers. He also freelanced for another NBC show called Art For Our Sake that profiled artists featured in Chicago’s Art Institute.

By 1944, he was offered a full-time reporter position for the Chicago Defender where he “had a knack for getting interviewees to speak their minds, even if their opinions were totally counter to his.” By the next year, he was honored with a “Page One Award” by the local chapter of the American Newspaper Guild (ANG). Williams writes that Durham was offered a “script analyst” position at MGM studios, but figured out soon enough that the “analyst” part of that position would be done not by him but by industrialist functionaries who only welcomed work supportive of their White supremacist capitalist vision. She points out that “no matter how tempting the opportunity to get into the film industry may have been, Durham would never cross a union picket line.” This is in stark contrast to the writer John Ridley, whose actions in crossing the union picket line for work led him to winning an Oscar for Best Screenplay for Twelve Years A Slave, ultimately catered to the film industry. Williams shows the price that Durham’s bold bravery cost him. What was worth more to Durham than a job in the film industry was the example he was setting to his son, and his fidelity to the same Marxist-Leninist principles Oscar Brown Jr. said he championed.

A promotions manager at the Chicago Defender, Charles Browning, came up with the idea of a fifteen-minute drama series called Democracy USA that would feature men and women who exemplified the principles of democracy through their lives and accomplishments. Williams focuses on one of his Democracy USA scripts, “Dr. Dailey and the Living Human Heart.” It explored the life of the distinguished Negro surgeon Ulysses Grant Dailey. President Truman praised CBS Radio’s Chicago affiliate-WBBM with a certificate of merit for its show Democracy USA written in part by Durham and produced by the Chicago Defender. This is the same Truman, who two years earlier, had the support of industrialists as he murdered hundreds of thousands of Japanese. After bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Truman’s certificate praised WBBM for “inspiring the youth to follow a path of citizenship” that follows the agenda of US industrialists who discouraged Black writers from encouraging a collective consciousness in their work. This agenda destroyed the path of self-determining peoples in the Jim Crow US South and abroad: in Japan in 1945, Palestine in 1948, Korea in 1950. Durham’s work is a testament to the growing number of Black workers that were becoming Communist because of Truman’s atomic bomb; people like Augusta Strong and Esther Cooper Jackson.

Unlike Truman and the industrialists, Durham’s scripts privileged values of collective struggle and liberation over the kind of individual success within the capitalist economy that industrialists like Truman wanted all Blacks to focus on. Durham’s script that best represents his commitment to Negro liberation is his Destination Freedom episode on Harriet Tubman, whose goal was collective struggle and liberation of all Black people in the Confederate South. Scripts on popular television and film by Black writers like Shonda Rhimes, Tyler Perry, Mara Brock-Akil are welcomed and propagated by industrialists because they privilege individual success over collective struggle and liberation. Durham’s work on Destination Freedom focused on the latter over the former and entered obscurity because of it.

Durham also worked with Irna Phillips, who wrote and created several lucrative radio dramas now popularly known as “soap operas.” Phillips’ stories dealt with postwar conditions like amnesia, alcoholism, or psychosomatic paralysis that Durham later used in his own series. He co-founded the Du Bois Theater Guild and conceived of a soap opera called Here Comes Tomorrow, which Durham called “the first authentic radio serial of an American Negro family.” In 1948, NBC and its affiliate WMAQ agreed to air a radio series. Conceived by Durham, Destination Freedom was to run weekly for half an hour. It featured “the lives and contributions of prominent Negro history makers.” The series showed the personal and political struggles of those Blacks who believed in radical change. Williams writes that Black leaders like Harriet Tubman, Benjamin Banneker, Katherine Dunham spoke to Richard Durham, hour after hour, as he sifted through the mounds of materials that Vivian G. Harsh, head of the Hall Branch Library, and her staff provided, and wrote for Destination Freedom. In her appendix, she also included a radio log of each episode from July 1948 to August 1950. His series included episodes about Harriet Tubman, Toussaint L’Ouverture, and William Lloyd Garrison, among others. Williams quotes J. Fred MacDonald as saying Destination Freedom was “one of the most damning critiques of racial abuse ever heard on U.S. radio.” The series received awards from the Chicago Commission on Human Relations, the National Negro Museum and Historical Foundation, and the National Conference of Christians and Jews. Williams identified one of the series’ abiding philosophies as “universalism,” which apparently seemed to justify Zionism. In interviews identified a connection between the “Negro’s sharecropping experience” and “the Jewish people struggling to create the new nation of Israel in 1948.” However, the 2014 reinstatement of a previously-fired Palestinian Professor Steven Salaita by the board of trustees of the University of Illinois, which published Williams’ book, underscores a stronger connection not “with the Jewish people” but with the Palestinians. Durham’s stories show a Negro people under racist persecution that is more similar in 2015 to the struggle of Palestinians against the Jewish people. Williams raises the question of why the WMAQ and NBC allowed Destination Freedom’s progressive sentiments and rebellious Negro characters on the air, and suggests that it could be because the program was aired only in Chicago. NBC also rejected several of Durham’s script ideas, including ones on Paul Robeson, and another about the U.S. bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

While Durham was pioneering, Williams notes that his scripts revealed the philosophy not of a revolutionary but of an optimistic reformer. When the radio station hired a new director who “massacred” Durham’s scripts, he decided to end the series. However, he started a legal battle with NBC because they revived the series without his consent or input, even though he owned the copyright to the series. Williams writes that records documenting the final outcome of the lawsuit were conspicuously missing from Durham’s files. He later landed a two-month contract with the United Packinghouse Workers of America in which he prepared a twenty-one page brochure called Action Against Jim Crow: UPWA’s Fight For Equal Rights. He was fired after he tried to pull together a caucus of all the key Black figures within the UPWA and set up the election of several Black officials to the merged leadership.

By the next decade, Durham’s reputation landed him an offer to work as editor of the newspaper of the then rapidly growing Nation of Islam called Muhammad Speaks. He developed a close relationship with Elijah Muhammad and successfully convinced him that “the Muslim’s best interests were served by keeping the Nation of Islam’s progress sectionalized from the rest of the paper.” This was based on Durham’s strict journalistic policy of maintaining a strong “separation of church and state reportage between Muhammad Speaks and the Nation of Islam.” He required Muhammad Speaks reporters to research their stories comprehensively to avoid the impression that the paper might be “mouthing off conspiratorial theories.” According to Durham’s brother Earl, Richard Durham worked to “get the Nation off King’s back.” When the NOI placed its printing press under the supervision of the Fruit of Islam (FOI), Durham happily left, but was soon offered a job writing for a WTTW TV series called Bird of the Iron Feather, about a detective who died in a crossfire “between black rebels and the police during a race riot on Chicago’s West Side.” By February 1970, national news magazines Time and Newsweek reported that the TV series’ half-million viewers made it the highest rated local production in WTTW’s history.

Despite this, after only twenty-one episodes within two months, the station terminated the series for a number of reasons, including Durham’s decision to defy the station management’s request that he change his concluding series storyline that had “police assassinating other police officers.” Here again, like the demands of the second director of the Destination Freedom series, he refused to cater to the White supremacist demands that should sanitize militant messages directed at Black audiences. Williams describes Durham’s collaboration with Muhammad Ali for his autobiography that was published by Random House, from his defeat of Sonny Liston to his defeat of George Foreman in then Zaire. Random House editor Toni Morrison said that Durham had “a theatrical eye,” enabling him to determine “what to throw out and what to include…what was interesting and what was not and how to make a scene…I found working with him very interesting.” For many reasons, Williams writes that the autobiography Durham collaborated on was “uneven…the tensions between the Nation of Islam’s restrictions, Random House’s deadlines, as well as Ali and Durham’s storytelling choices kept the book from being a cohesive whole.” In Ishmael Reed’s biography of Muhammad Ali, Durham’s longtime friend Bennett Johnson tells Reed that Ali agreed to the autobiography because Durham was collaborating with him. Johnson also provides more insight than Williams into Durham’s late 70s business foray with the NOI—of which Williams observes was “painful” for Durham’s wife Clarice. The venture ended unsuccessfully and consequently reinforced Durham’s 1938 review of Carnegie’s book that no “how-to” book can solve our social and business problems. Williams’ last chapter, “Black Political Power,” describes Durham’s last years as a screenwriter for the pioneering Black mayor of Chicago, Harold Washington. Williams stretches the definition of revolutionary when she writes that Washington becoming the mayor of Chicago was “nothing short of revolutionary.” Durham, in this capacity, was purely reformist. He worked within the electoral system funded by the same industrialists like Carnegie whose self-help philosophy he excoriated in 1938. His screenplay on Harriet Tubman portrays her as a revolutionary against chattel slavery, and additional scholarly research could shed needed light on how Durham’s work opposes wage slavery.

Like the historian Macdonald, Durham might have educated Black masses about revolutionary thinkers, but he functioned primarily as an optimistic reformer. Durham’s work is a living example of Addison Gayle Jr.’s 1977 article, “Blueprint for Black Criticism”:

“Black people must demand realistic paradigms from Black artists: they must demand that characters be modeled upon such men and women as Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, and Martin Delany; H. Rap Brown, Fannie Lou Hamer, and those countless mothers and fathers who sacrificed dignity and manhood in order to prepare their young to deal with a nation which ranks among the tyrannical in history.”

Richard Durham’s body of fictional work came closest to fulfilling this paradigm, perhaps more than any other writer in the twentieth century. Williams succeeds in her book-length account of the totality of Durham’s contributions and advocacy; however, her study underestimates the repression of the McCarthyist climate in the United States that persecuted Communists and Communist sympathizers like Durham. Oscar Brown Jr. said that Durham believed that Communist philosophy was more in line with the liberation of Negroes. However the opportunity to practice this was erased when Durham sought employment by local radio stations that wanted the theme of his work to celebrate democracy. This book did not elaborate on the way Black writers like Durham had to hide their belief and appreciation for Communism during McCarthyism. Durham’s life story is in one way a story about the success of McCarthyism in successfully silencing Communist sympathy except for faithful Chicago listeners of Durham’s work. What would enhance Williams’ study is a look at Durham within a theoretical framework that celebrates collective struggle over individual capitalist achievement.

Special thanks to Ian Rocksborough-Smith for introducing me to the work of Richard Durham in 2007.