Emese Ilyes

How do we continue to find the words with which to reach each other even while we are collectively drowning in grief? I found myself frequently lingering on this question over the past three months. Some of us have lost futures that we poured our souls into building, and we were more fortunate than most. Others were, and today are, risking their lives to carry our sick bodies through this virus. Many more are disproportionally exposing themselves and their families to illness and face the possibility of death by ensuring that people at home have access to groceries and necessities. Already, in the US, more people have died from COVID-19 than during World War II – a majority being people of color because of the systemic oppression and anti-blackness that is endemic in the United States, and before vaccines and medicines will be available, millions more around the world may perish.

The collective grief is overwhelming, even if not named. Thirteen months ago, my mom took her last breaths and the composition of my world was radically altered. The years leading up to her parting were painful. Long before her death, I could feel the weight of grief in my cells. This pandemic is awakening a similar sense of loss within many of us, including me. This pandemic has at times allowed us to shed the illusion of our autonomy as each of our simple actions reverberates in our communities, impacting and potentially killing the most vulnerable among us. The pandemic exposed the flimsy artifice of an economy built on greed and deception, unraveling more questions. How do we proceed now that we can no longer hang on to the notion of certainty as our institutions are crumbling with each passing day? At times, I feel like academia has an obligation to enter these questions, but these times are admittedly fleeting. This article is a relic of these fleeting moments when I contemplated whether there was meaning within the academic enterprise.

One fragment of these fleeting moments is the question of whether academics have a role in advocating for people’s full humanity during these times when questions are asked about whose life is worth saving ,when our health care system is under stress, when not everyone will have access to ventilators. Academia is responsible for the invention of many of the categories that will determine whose life is worth investing scarce resources in. It is possible that now there is a role for academics to ensure that each person’s full humanity is being recognized. Perhaps engaging in these conversations is a way for us academics to hold ourselves accountable. Following this issue, I will explore whether academia in the time of the pandemic may support the reawakening of critical intimacy and hope by offering accessible, interdisciplinary works that honor the co-construction that everybody is engaged in.

Refusing the Simple

Sometime in the middle of March, the Italian health system became overwhelmed and a decision was made that in the event that not enough ventilators are available, those 60 and above would not be given access to them. Italy has one of the most advanced health care systems and during the height of the first wave, people above sixty were dying alone, gasping for breath. In the residential neighborhood of Brooklyn, where I live, throughout March, April, and May, I heard the sound of sirens several times an hour. The hospital, a ten-minute walk from me, had two morgue trucks parked outside of it, the generators humming all day long. Walking by, I saw bodies wheeled up the ramp into the trucks. Here, too, similar conversations were and are taking place about whose life will be worth saving.

When my mom was first brought into the intensive care unit, she was two days past her 60thbirthday. The doctor pointed to a screen next to her bed and told me that the tiny fluttering flap was my mom’s collapsed lung. To me, it looked like the broken wing of a delicate butterfly shuddering in the breeze. Heart failure, late stage diabetes, and colo-rectal cancer told a complicated life story of communism, persecution, immigration, alienation, and sexual abuse. I tried to translate this complexity to the doctors and nurses as a way to explain why my mother appeared to resist their attempts to save her

Fundamental questions about the value of individual lives are being raised around the world right now, including in New York City. Within the political, legal, and medical realm, academics are often granted disproportionate power to shape or influence the constructs that are applied to the complexity of the human experience. Ethnic studies scholar, Lorgia García-Peña, reminds us that these standards set by academics within “humanities and social science curriculum—are actually grounded in white supremacy, but are masked as objectivity.”

And these standards, these categories, as they are used to scaffold society, inevitably reinforce these white supremacist, dehumanizing notions. As a brief example, following industrialization in the nineteenth century, new notions of human productivity were established that corresponded with the development of large metropolises. These notion of human productivity devalued certain ways of being in the world because they did not conform to the new industrial norms. People who are today labeled as intellectually disabled were separated from families, forcefully sterilized, segregated within abusive asylums, and in some parts of the world, exterminated. Today, in order for people to receive necessary services like funding for in-home caretakers, they must fall within certain categories, that were built on eugenic, white-supremacist ideologies. Today, these categories both oppress and liberate. How do these categories – and all of the assumptions that float about them – function within the intensive care units? How can academics, who are too often allowed to be the arbiters of the value of the human life, ensure that human lives are held in their complexity and that categories like intellectual disability are not used to justify withholding lifesaving resources? In other words, can academics work from within the very same institutions that promoted eugenicist ideas to breathe life into a more equitable, humane world? Academics are not the only entities with the power to expand the moral imagination, but I believe they hold a special obligation to commit to doing so because they, we, have been complicit, we have been phenomenally successful in institutionalizing dehumanization.

The allure of abstractions feels like a deliberate act of violence during a pandemic, as thousands perch at the edge of life, and millions more experience deep precarity. Intellectual disability is not just an academic category. The label shapes the realities of people, including people I love, like one of my dear friends I had the joy of collaborating with and learning from many years ago. She went by ‘The Boss’ and was in her seventies when she published a series of letters to the world. In these letters, sent to the community on the west coast where we lived, The Boss articulated a yearning for love and touch that was sensual and deeply human. These were the same types of touch and the very emotions that were considered dangerous and even criminal within the systems structuring her life., the system that criminalizes sexuality for those labeled as intellectually disabled She did not have a lover. She did not have children. She spent her nights within a segregated all-women group home, rode a segregated bus to the sheltered workshop, where she spent her days creating art about her desire for love.

Notions about which lives are worth saving are, in part, influenced by academic theories and studies. For the Boss, the group homes she lived, the sheltered workshops she worked at, relied heavily on academic knowledge production to, more often than not, justify limiting her freedom. Can we live with ourselves if our work is in some way used to justify someone’s death? My friend does not have children, does not have grandchildren, does not have a prestigious position, does not have the protective cloak of wealth. Like millions of others around the world, she is at risk of dying if she is infected with this virus. What can academia do to respond? In the fleeting moments of faith in academia, I imagine that academics will insist on ensuring that contributions are accessible and relevant and that doctors and ethicists are drawing on the socially just material to expand what it means to be human instead of shrinking the horizon of possibilities.

Academics can center the particulars of lives while interrogating the systems that flow through bodies. In the hospital with my mom, I wanted the doctors and nurses to see the systems that pierced her organs. I wanted the instruments to identify the violence of the communist dictator in her cells. I wanted the bloodwork to reveal her dedication to her students in Transylvania, and that despite the decades separating her from them, she continued to think of her students every day. Would the colonoscopy tracing the outline of the tumor also show the way alienation in a land that never embraced her roots tore into her soul? There were ventilators and I was given the gift of another year with my mom. Those remaining precious months were not easy. The vomit. The agonizing pain. Yet, there were moments, little glimmers of togetherness that reminded me of a time before her trauma festered, these moments of love will nourish me for the rest of my days. These moments would not have been possible if there were not enough ventilators.

The radical intimacy of physical distancing

When we collectively experience the intensity of societal rupture, like the one instigated by the pandemic, I imagine ways that academics may engage with the relational dialogues that are circulating in the air. Philosopher of science, Helen Longino, has examined the way scientific ideologies, practices, and institutional structures privilege some ways of knowing over others, often leading to not only misrepresentation but also violence. A fundamental shift in scientific structures requires what Longino calls the tempered “equality of intellectual authority.” This is the structuring belief that every perspective is regarded at the outset as capable of generating useful intellectual interaction. How would an academia that existed only through equality of intellectual authority sound right now? Whose voice would be centered during the age of the coronavirus?

Disconnecting from the dialogues happening around the world – at the grocery store, in the emergency room, through memes on social media, and more recently, through global protests rallying against white supremacy – renders academic work not only irrelevant but obsolete. Language forged within ivory towers, often by ivory people, cannot possibly acknowledge the value of every perspective as capable of engaging in valuable intellectual interactions. This results in what Maxine Greene calls ‘anesthetic language’—language that is dead, that cuts the conversation short, that is one sided, inaccessible, and out of reach. People are using this time to shake up the definition of what it is that we do, who it is that we are. We are vulnerable. Porous. Radically dependent. The self-autonomous bubble that academic disciplines, capitalism and other structures of power have forged is now fractured. Leaking through the cracks of the artificial armor of autonomy is a radical kind of intimacy, with the world, human and non-human. In this moment in time, swollen with grief, we are becoming intimate with our relation to the world and each other. In order to continue to exist, we have to recognize our coexistence by limiting our touch with others while crying out in solidarity against injustices.

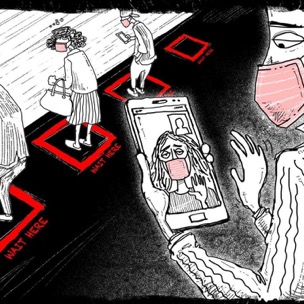

We are discovering new kinds of intimacies. Through technology, we find ourselves in each other’s bedrooms, at a coworker’s kitchen table as their children prance in the background. We yearn to connect, to belong, as my friend in the sheltered workshop did, and we make ourselves emotionally available to do so.

For many years, before my mother was hospitalized, she lived in what I understood to be devastating isolation. She was financially dependent on her abusive husband with whom she lived in a land in which she never successfully transplanted her roots. Together, they lived in poverty and isolation. During those decades, she did not seem to hear me or see me, though I tried to be there. I longed to be her daughter. Still, the few dollars my father would give her as an allowance would be spent on sending me periodic packages containing baked goods made from recipes passed down through generations of Transylvanian women and photographs developed from 35 mm film. The photographs were of birds in the forest behind their house in Michigan, a house they would lose in the 2008 recession. In her isolation, my mother intimately knew each bird among those trees. I have come to accept that they might have known her better than I ever did. On the back of each photograph, she wrote a story about the bird from the perspective of the bird. In my years of theorizing resilience and survival, I have often struggled to capture the kind of resistance my mother demonstrated.

Greta Thunberg, a leader in climate change activism, recently said in an interview, “I’m very tiny and I am very emotional and that is not something people usually associate with strength. I think weakness in a way can also be needed because we don’t have to be the loudest, we don’t have to take up the most space, and we don’t have to earn the most money…We need to care about each other more.” Like Greta’s invitation for all of us to recognize care as more valuable than traditional conceptions of strength, my mother’s tenderness toward the birds helped me reconsider notions of resilience. Amidst her painful struggles with trauma induced paranoid schizophrenia she never stopped seeking meaning and connection. I did not find such rich articulations of vulnerability, strength and resilience within the academic texts I scoured over. If academic disciplines understand that everyone is entitled to shape the constructs that are foundational to our understanding of what it means to be human, then it is time to listen. Listen to the way people are processing the physicality of social distancing, the way it is allowing many to engage with the beautiful, ordinary miracle of the intimate presence of the world. Along with the deep grief, the unbearable weight of all that we are losing, the obvious inequities stemming from anti-blackness that are exacerbated by the pandemic, there is this awful contradiction of radical intimacy and quiet presence.

How do we capture this complexity? There are precious and fleeting moments when the world is awkwardly and imperfectly united in the struggle for survival, and more recently, in the global protests against police brutality and white supremacy. Academics cannot continue to suture themselves to the same words and worlds that were used to forge the institutions of abuse starkly exposed by the pandemic. Maybe, there is a need for more poetry – not just for appreciating text and aesthetic descriptions, but for the allowance and recognition of feeling feelings that are often denied within the sterile knowledge production process. Moving toward what Maxine Greene calls “wide-awakeness” requires conscious effort to think about our own condition in the world; without keeping ourselves awake, it is not possible to lead a moral life. Is it possible to remain awake while cloistered in academia?

Eyes open, Heart broken: At a distance, together in critical hope

Knowledge production – much like the lives that contribute to it – has always been a fluid and messy relational process, not a static objectified representation of a shared world. Mourning, too, is a process. Neither can happen right now without critical hope. Jeffrey Duncan-Andrade writes about hokey hopeas an enemy of hope. It ignores inequities while offering sedating guidance, such as spoon-feeding the American dream of individualistic hard work to youth who are in under-resourced schools, Or saying things like we are all in this together during a pandemic, as black people die at a disarmingly higher rate than white people, due to the systemic anti-Black oppression that defines the core identity of the United States. Hokey hope during this moment in history delegitimizes consuming pain and unspeakable loss. Critical hope, on the other hand, demands commitment to radical transformation and active struggle. Necessary radical transformation cannot occur unless we believe that this time has the potential to address deeply rooted inequities in our society. This requires critical hope in others and ourselves. Critical hope transforms the pandemic into what Arundhati Roy calls a portal, a gateway between this world to another.

Can academia cultivate and foster and represent this kind of critical hope that ushers us toward new worlds? Can spaces that were built to bolster white supremacy even pretend to have a hand in dismantling it? I see critical hope in the streets. I see critical hope in the heartbreakingly tender expression of Gianna Floyd, George Floyd’s little girl, as she exclaimed, “My daddy changed the world.” I have learned to see that there was always critical hope in my mother’s life, in her wild birds. I’m not sure academia will ever be a source of revolution, but I do know that with this palpable critical hope spilling into the streets, we carry each other through the unthinkable to come, from this world to the next. We have no other choice.