Maria Alejandra Lopez

One thing is to travel and another is to travel as a Colombiana* (Spanish female version of Colombian). Colombia is a country populated by around forty million people, at the northern tip of South America. We are known for exporting coffee beans, emeralds, and flowers, amongst other very valuable natural resources. However, at the start of the 1980s, a very distinctive figure emerged from the penumbra of perversion, illegality, and violence. It seemed as if my country’s accomplishments, perplexing landscapes, oceans of seven colors, and the human and wildlife diversity we are all so proud of, were all about to be melted into one name: Pablo Escobar. Outside of Colombia, ordinary people’s knowledge of my country revolves around cocaine, violence, shoot-outs, cartels, drugs, ‘sexy’ women, ‘hot’ accents, and sometimes here and there, coffee (I know right?!). One of Colombia’s darkest and most violent times in recent history has Escobar’s name inscribed with hundreds of innocent people’s blood. Every Colombian family in the last thirty years (including mine), has had at least one violent encounter caused by drug-related wars, in which both legitimate (State) and illegitimate (cartels) parties were involved. These horrifying events were the motivation for many of our families to migrate to Western countries like Australia, France, Spain, or the United States in the 1990s right after the dismantlement of cartels. As a result, many Colombian-born children from the 1980s-early 2000s who later migrated to the countries mentioned above, are often called “hijos de la Guerra,” or children of war in English. We, children of war, are the hybrid identities and faces abroad that embody the continuous effort of unlearning a violent Colombia by constantly repudiating it. So, how does this historical context connect with me, as a woman and Colombian traveler?

As a Colombian, I dare say that we all carry the stigma of sharing birth countries with this grotesque criminal recognized worldwide for his cocaine trafficking. Whether his ties to the United States market helped his image get more fame or not is out of my concern. But what is a mix of shock, sadness, perplexity, and rage, is that Escobar’s name has monopolized all Colombian-related knowledge abroad, even in remote places, where this name is synonym for Colombia.

During the summer of 2016, I visited Paris with two of my closest friends (also Colombians). On a chilly Parisian night, we decided to eat pizza at a small Italian restaurant in the heart of Paris. Of course, the question par-excellence of the host in every country is, “what part of the world are you visiting from?” The waiter at this restaurant wasn’t the exception, and as he asked, we excitedly exclaimed we are all Colombians visiting Paris. Instantly, the guy smirked as if he knew something. He then outwardly divulged, “oh, Pablo Escobar,” thinking perhaps we would acclaim or applaud the one and only thing he thought he knew about us. I immediately suggested my objection by stating, “EL NO BUENO” in a simple and broken easy-to-understand Spanish to French. Embarrassed (at least I hope he was), he took our order and went on to play Shakira for us, as to perhaps alleviate his indiscretion and imprudence. True story!

Little did I know this scenario was to be repeated at a remote corner store in Germany and in a small town in Italy during my summer 2016 Europe trip. These people’s only knowledge and imagery of Colombia was wrapped around Pablo Escobar and cocaine, as if my friend and I were ambassadors for his long-lasting cartel. No ethical person would have the audacity to compare a decent Colombian person to Escobar (or any drug lord)—this is just irrational and highly disrespectful—but I don’t personally blame them because I don’t think they know half of the damage of this legacy. The narco-style legacy of not only Escobar, but other powerful cartels in the 1980s, left a ruptured society regardless of class or socioeconomic status. Note that when I say “narco-style,” I refer to the overall transformation of aesthetics in many spaces of society. For our purposes, I will touch on narcotrafficker’s fetishization with female bodies, where plastic surgery begins to symbolize their excessive power, wealth and twisted sexual fantasies.

The creation of this kind of lifestyle came along with the exploitation of the female body—the deformation of it by excessive plastic surgery to satisfy sick sexual instincts, the recruiting of young boys from poverty-stricken areas to be trained as sicarios (mercenaries), countless mothers mourning deaths of their young sicarios that didn’t get past their 20s, excessive materialism and the overwhelming use of ‘bling’ are both praised and desired in lots of today’s Colombian society (this includes Colombian expats). One can say the fetishization is with money, or one can say it is with women. That one is for you, the reader, to decide.

Pablo Escobar and I share the category of Colombianness. In this context, he was the cause and now I am the effect, or product of this war. As an effect, I feel I have the responsibility to help clean up the mess these horrendous minds did to the image and reputation of my people. Most of us do not deal drugs, neither consume or even less, nor have we seen cocaine in person. Today, series like “Narcos,” not only impose these violent stereotypes upon us, but also deliver historically inaccurate information, overly exaggerate accents, romanticize war, paint a picture of an exotic and savage Colombia, make the United States’ DEA (Drug Enforcement Agency) the saviors of their own crafted “War on Drugs,” and fail to explain the aftermath and effects of this cruel and violent war where many Colombians were and are victims. But hey, that is Hollywood! I urge people to not let Hollywood or the media educate you. The influence of media is more bad than good—they find ways to pollute our homes with insensitive material. Our minds and intellect potential become subjects in their million-dollar lab experiments. They become richer in money and we become poorer in judgement, analysis, and overall sensitivity towards others.

Colombians aren’t the only ones facing imprudent and imbecilic stereotypical comments. Considering today’s political and social context, I urge my readers to think before robotically imitating stereotypes that could ultimately hurt people’s feelings, like me, when I get compared to Escobar. We tend not to know each other’s stories, yet we talk and judge as if we do. Aside from not making sense, it says a lot about us as people and it only creates bigger gaps between us. Conversation and dialogue are always great ways to soften the stressful moments we are going through politically and socially. When we are genuinely interested in opening conversation with others, it inevitably triggers endless possibilities of empathy and solidarity. Try it.

Things to remember:

-Not all Muslims are terrorists.

-Not all Black people are criminals.

-Not all Brown or Latinos are Mexican, rapists, or criminals.

-Not all White people are prejudiced racists.

-Not all Colombians are cocaine ambassadors or related to Pablo Escobar or any other drug lord.

I want to leave clear that by speaking about these stereotypes, I am not necessarily prolonging them. I think it is necessary to TALK and communicate social and political distresses—I believe the lack of communication and comprehension in our communities is exactly what has caused the reproduction of hate, stereotyping, bullying, homophobias, and racial phobias in this world. Ignoring the issues won’t fix them.

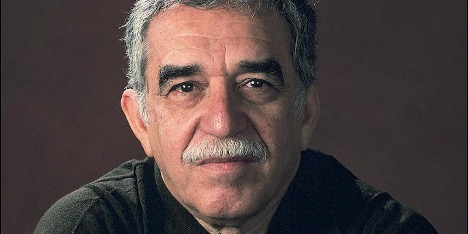

I am not Pablo Escobar nor a drug dealer; however, with a Colombian identity in the world, I have the responsibility of creating awareness about my history as a Colombiana expat in the United States and Colombian ambassador in the world. I wanted to share my story as a person that sometimes feels judged for sharing nationalities with a grotesque criminal. Why don’t they compare me to Literature Nobel Prize winner Gabriel Garcia Marquez instead? Now that would an honour!

*Words with an asterisk are either slang or Spanglish words.