By Jamie Brooks

Bruce Lee (see the exhibit Be Water, My Friend at the Wing Luke Museum, Seattle), according to Paul Bowman, was a “chiasmatic” (diagonally across something) figure who transcended race, gender, and sexuality. Part of the late 60’s vogue of Asian philosophy in the West, Bruce Lee films were fantastic choreographies of aestheticized, masculinist violence but also, cultural translations of Eastern and Western models of masculinity. He was according to Bowman, the Asian “phallic hero” to his Western, largely- male fan base.

Bruce Lee (see the exhibit Be Water, My Friend at the Wing Luke Museum, Seattle), according to Paul Bowman, was a “chiasmatic” (diagonally across something) figure who transcended race, gender, and sexuality. Part of the late 60’s vogue of Asian philosophy in the West, Bruce Lee films were fantastic choreographies of aestheticized, masculinist violence but also, cultural translations of Eastern and Western models of masculinity. He was according to Bowman, the Asian “phallic hero” to his Western, largely- male fan base.

Blockbuster wushu (martial arts) films from Hong Kong trafficked in the usual, presumptuous modus operandi – Asiaphilia— of Western consumption of subtitled martial arts films. Says Bowman, they were a largely mindless, Orientalist encounters with Eastern, marked by conquest and appropriation. For monolingual Western audiences, these subtitled or dubbed films made them more “Chinese” underscoring the linguistic difference between East/West. They “funny” for Western audiences, removing the possibility they could be considered weighty cultural artifacts.

But by producing a residual irrationality, they also became an unexpected boon and an unruptured pleasure endlessly fascinating to hardcore fans. Wushu films peddling in difference, a disruption of cinematic identification, lended to their fetishistic appeal. Low brow, down market amusements with a palpable (racist) foreignness to laugh at, it was their very foreignness that helped Bruce Lee translate and then crossover to Western audiences.

The unlikeliness of such an auspicious cultural exchange illustrates a relationship between translating difference and the omnipresent possibility of “queer”. A Bruce Lee film was kinda queer because it celebrated the possibility an Asian as holding the usual markers of an action hero to a Western fan base. According to Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner’s seminal work on queer theory, something is queer when it has left the lexicon of difference- as- pathological and inadvertently enters the visible mainstream of the official public sphere.

The existence of the unpredictable, the queer, gave Bruce Lee a certain cultural legitimacy. Wushu films made it possible for Lee to cross over. He could change from Asian stereotype, to embodying desirable male hero attributes that allowed him to sneak past normal distinctions of East and West, and back again. Bruce Lee transformed to desirable action hero to his male fans, kinda queer, defiantly pushed up against heterosexual-only social orders.

Tony Silva describes this dominant “straight culture” as a matrix of beliefs, interpretations, and alignments, often with childbearing cultural groups and institutions. His study found straight culture isn’t merely a collection of attractions and sexual practices, but more entry into a society of deeply heteronormative institutions. School systems and their social networks of mostly straight parents he observed, form its underpinnings where social pressure to “participate in childbearing responsibilities” was the main factor for same- sex attracted study participants to identity as straight. Social pressure to be a parent that doesn’t necessarily emanate from an overt homophobia or gender conservatism.

The institutions of straight culture could control how study participants identify but had less control over study participant’s same-sex sexual desires and behaviors. But the power of straight culture producing pressure to be an upstanding, family raising citizen, also produced fear of LGBTQ+ identities. By implication, to be LGBTQ+ is to be less reputable, more selfish. Silva found fear of an LGBTQ+ identity as a reflection of a sort of straight culture hegemony, was associated with increasing the odds of straight identification for men (and women) despite varying degrees of same-sex sexuality.

The study concluded straight-identified- yet- not- so- straight behaving male study participants were granted and retain, considerable privilege relative to LGBTQ – identified people. On one hand the study revealed the queer possibility for a fluidity in sexuality not driven by some preordained moral judgement. But is also revealed a present-day social pressure to appear straight and where study participants sought to escape the social predations that come with LGBTQ identities. By not identifying as gay they could preserve their privileges and protect themselves from sexuality-based discrimination and prejudice that also leave intact the inequalities between straight and queer.

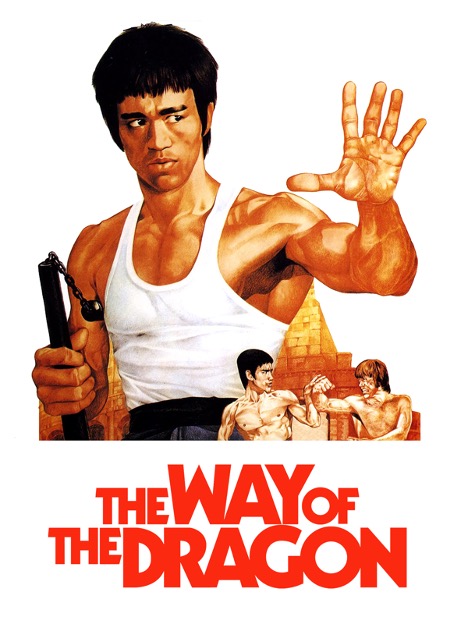

Part of preserving straight culture for men was an outwardly masculine presentation. Hypermasculine yet winking at the homoerotic Bruce Lee films from the 60’s and early 70’s, were embedded in a historically similar straight culture that enjoyed the same benefits. They offered an alternative to the concept of homosexuality by referring to a temporary desire for all things masculine. They negotiated this terrain through the exhibition of the racial other. The homoeroticism of films like “Way of the Dragon” emerged through what queer scholar David Eng, called the Western “racial castration” of Asian men. The film’s use of a denuded masculinity helped tread the line between a portrayal of an essential masculinity and crossing over into the homoerotic. The compulsive attraction to make Bruce Lee conform to standard male characteristics of power ended up collapsing rigid gender and racial categories.

Part of preserving straight culture for men was an outwardly masculine presentation. Hypermasculine yet winking at the homoerotic Bruce Lee films from the 60’s and early 70’s, were embedded in a historically similar straight culture that enjoyed the same benefits. They offered an alternative to the concept of homosexuality by referring to a temporary desire for all things masculine. They negotiated this terrain through the exhibition of the racial other. The homoeroticism of films like “Way of the Dragon” emerged through what queer scholar David Eng, called the Western “racial castration” of Asian men. The film’s use of a denuded masculinity helped tread the line between a portrayal of an essential masculinity and crossing over into the homoerotic. The compulsive attraction to make Bruce Lee conform to standard male characteristics of power ended up collapsing rigid gender and racial categories.

Going from hypermasculine to homoerotic produced alternative worlds beyond race, gender, or sexual identity. Lee’s brutal display of speed and power was amplified by his beauty. His beauty-to-other- men allowing him to wander into a kind of feline, even feminine territory that in turn, temporarily allowed for same-sex desire to be evident in the wider culture.

Incontrovertibly masculine and thus “safely” desirable to other men, made Bruce Lee able to throw off long-established gender presumptions. Masculine, skilled, and beautiful produced a magical quality that allowed fans to forget about their anxieties about LGBTQ+ identity or the racial other. This made violently homoerotic Bruce Lee films “carnivalesque”. They were powerful creative events and not merely a spectacle, where viewers could transcend the sacredness of straight culture and racial difference. Instead, they could celebrate the process of change and evolution itself rather than a dogmatic hostility towards such things. A celebration that created alternative worlds beyond the absolution of straightness and racial chauvinism. The films could dissolve the artificial distinctions and boundaries between them.

Thus, a queer Bruce Lee could forward the improbable. A mainstream, hot, Asian action hero for Western fans. Lee films became an event that made available a different understanding of membership in the mainstream. Male audiences could aspire to be him for many reasons including because he was sexy, which risked emasculation but also, demands a kind of impetuous gender flexibility so long as Lee remained unmistakably masculine. The transpiring pleasure of identifying with him, doubtlessly facilitated by his ubiquitous shirt lessness, was audiences assimilating queerness without having to formally adopt its identity.

Fight sequences enhanced by this masculine aesthetic and definitely more satisfying because of it, are defiantly queer. They are commentary on the possibility for sexuality that already belongs in the public sphere. As noted by Bowman, they weakened the literary, philosophical, and epistemological foundation of Western domination by making fluid and open-ended, encounters between cultures.

In real life Bruce Lee himself gestured towards a postnationalist, liberal, multicultural ideology. Lee, Orientalized, and representative of Asian culture, brought a sense of foreignness, and primitivism to audiences that could also trouble their assumptions about Asian men through the potential for a secretive superiority.

But Bruce Lee films could also remove these anxieties about foreignness through a teachable moment. He was a muse for a postmodern self-construction. Hard, sexy, cool, and (mostly) not white, he kicks white, American, Russian, Japanese, Italian, imperialist, colonist, capitalist, and gangster ass to the delight of his male, gamer boy audiences of the day. As noted in Martial Arts Film in the 1990’s, through “the physical pleasures of the male body”, Lee films gave viewers the unlikely experience of being the other, an outsider, or being denied an identity by the ruling order.

Fans could unconsciously feel what it is like to be Asian to the Western gaze and to feel some of the characteristics of same sex desire through the simple pleasure of tightly choreographed fight scenes. Bruce Lee films incorporated liberty as a method of learning about difference that made them decidedly anti-authoritarian and well, queer.

Bruce Lee films subjected straight and racist cultural institutions to a deconstructive questioning and became a testament of the virtues of difference and individuality. They were the rare instance Asian men could play authentic and authoritative masculine roles to Western audiences. Bruce Lee could be a masculinity of a different sort much because he possessed a martial arts prowess that held a confirmed masculinity in a global market. But also, he made it possible to ignore the difference between Chinese masculinity and Western, straight culture from LGBTQ+, while he entertained his audiences with spectacular fighting.

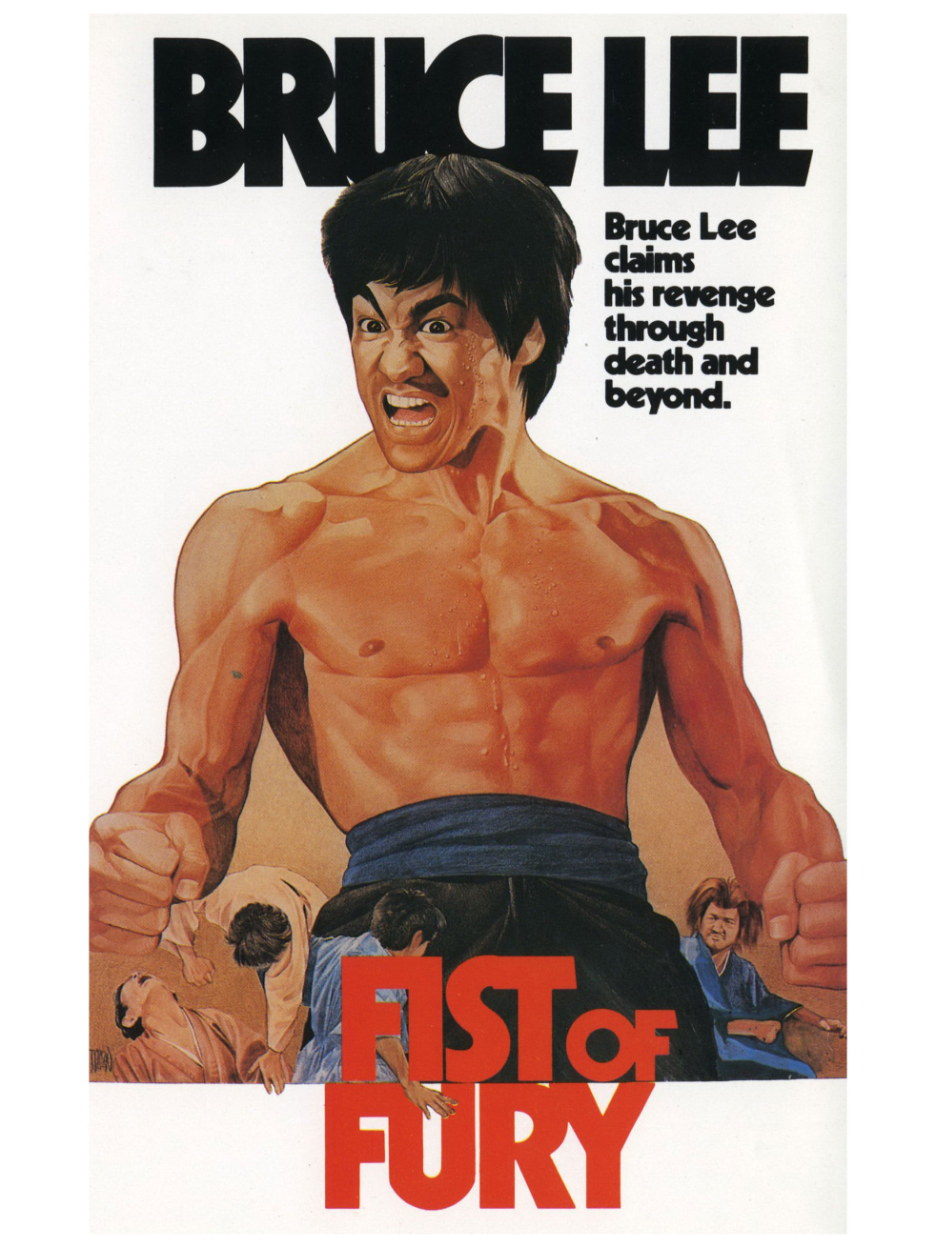

In his 1972 film Fist of Fury the use of foreignness and masculine eroticism in spectacular action could show audiences a potentially fantastic, other world. When Lee, who plays Chen Zen, takes off the shirt (the uwagi) of his Keigogi, we knew the climax, the impossible fight, was about to begin. The scenes use of his impossibly sleek body only boosts the pleasure of the Hong Kou dojo fight sequence. His preternatural six pack abs and pecs cut like diamonds glistening in early 70’s technicolor, were an integral part of the ridiculous enjoyment. Who cares if it is impossible for one man to thump twenty or so bullying Japanese students — not to mention, the chubby, and thus unwished-for master, played by actor Yi Feng — Lee is indisputably beautiful doing it? And audience’s risked nothing feeling their nascent animal magnetism because Lee could kick ass like nobody else.

In his 1972 film Fist of Fury the use of foreignness and masculine eroticism in spectacular action could show audiences a potentially fantastic, other world. When Lee, who plays Chen Zen, takes off the shirt (the uwagi) of his Keigogi, we knew the climax, the impossible fight, was about to begin. The scenes use of his impossibly sleek body only boosts the pleasure of the Hong Kou dojo fight sequence. His preternatural six pack abs and pecs cut like diamonds glistening in early 70’s technicolor, were an integral part of the ridiculous enjoyment. Who cares if it is impossible for one man to thump twenty or so bullying Japanese students — not to mention, the chubby, and thus unwished-for master, played by actor Yi Feng — Lee is indisputably beautiful doing it? And audience’s risked nothing feeling their nascent animal magnetism because Lee could kick ass like nobody else.