by Mark G. Sheppard, M.A., M.P.P., PhD

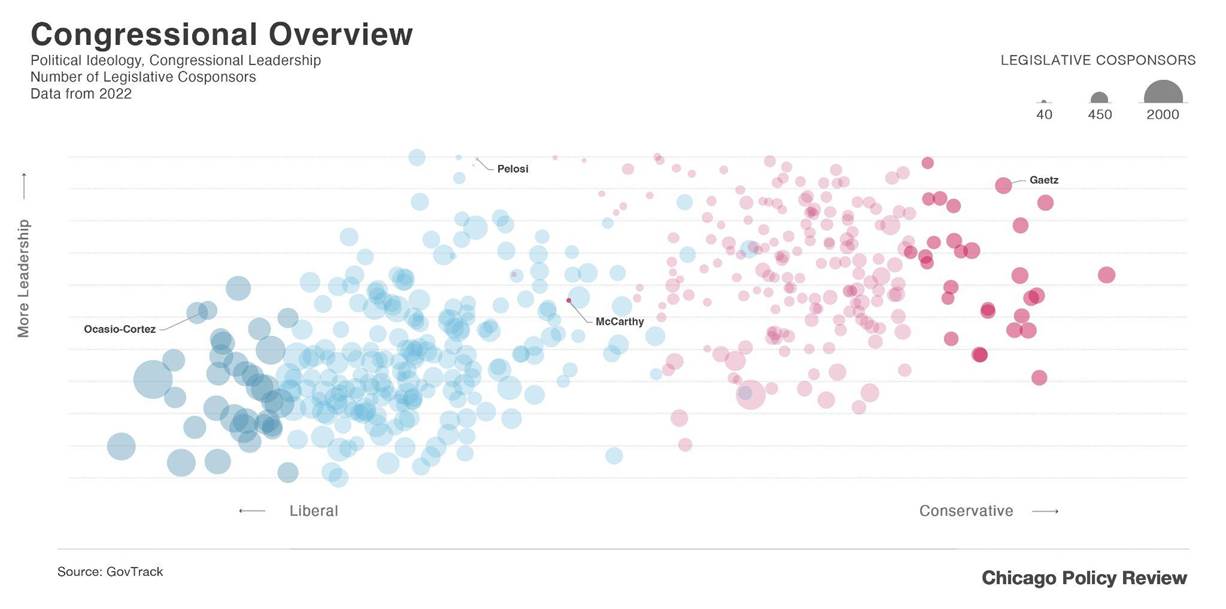

Once again, Congress appears deadlocked. Following the tight 2022 midterm elections, Democrats managed to maintain a slim majority in the U.S. Senate, but narrowly lost the House. Recent senatorial defectors threaten the unity of the Democratic Senate majority and the prolonged race for Speaker of the House revealed the instability of the Republican House majority. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy is simultaneously a moderate-conservative and a Trump-Republican, though he faces fierce opposition from the Trump wing of his caucus, and there is considerable uncertainty regarding his true policy priorities. These factors all add up to a limited probability of any accomplishments in such a contentious political environment in Congress and the prospect of large-scale legislative reforms seems very unlikely.

However, even in such a tumultuous environment, the prospect for legislative progress is not lost. Congress can still make technocratic adjustments to existing federal programs and marginal changes to formal policy definitions that could have a significant positive impact while avoiding politically untenable headlines. Such minor changes can also be enacted through non-traditional parliamentary avenues such as the budget reconciliation process or simply attaching incremental changes to an omnibus-style federal budget or companion bill, potentially circumventing major political fights. One such possible reform is updating the federal poverty line, which is both politically possible and a worthwhile policy.

The federal poverty line is a federally-set measurement of the minimum amount of annual income needed for individuals and families to pay for essentials. If an individual’s or family’s income falls below the poverty line, the federal government considers them ‘in poverty’ and eligible for certain additional federal assistance programs. Currently, the poverty line for an individual stands at $14,580 a year, and scales slightly with the size of a family, for instance for a family of six the poverty line increases to $40,280, regardless of where a family lives.

Additionally, this poverty threshold is painfully low, and the poverty line has not been truly updated since 1964. Recently, Members of Congress have introduced legislation to adjust the poverty line. Although such previous bills gained little traction, reintroducing legislation in successive Congresses almost always results in more supporters, ensuring that legislative persistence can yield progress on the topic. In previous legislative sessions, Democratic and Republican approaches to the topic have differed. Progressives introduced legislation to comprehensively increase the poverty threshold. Conservatives introduced competing legislation to count welfare benefits as income, which would potentially disqualify welfare recipients from future benefits. Although both bills are self-described as updating the poverty definition, the legislative intent of the conservative bill is to reduce government spending on welfare programs, not meaningfully update the definition of poverty.

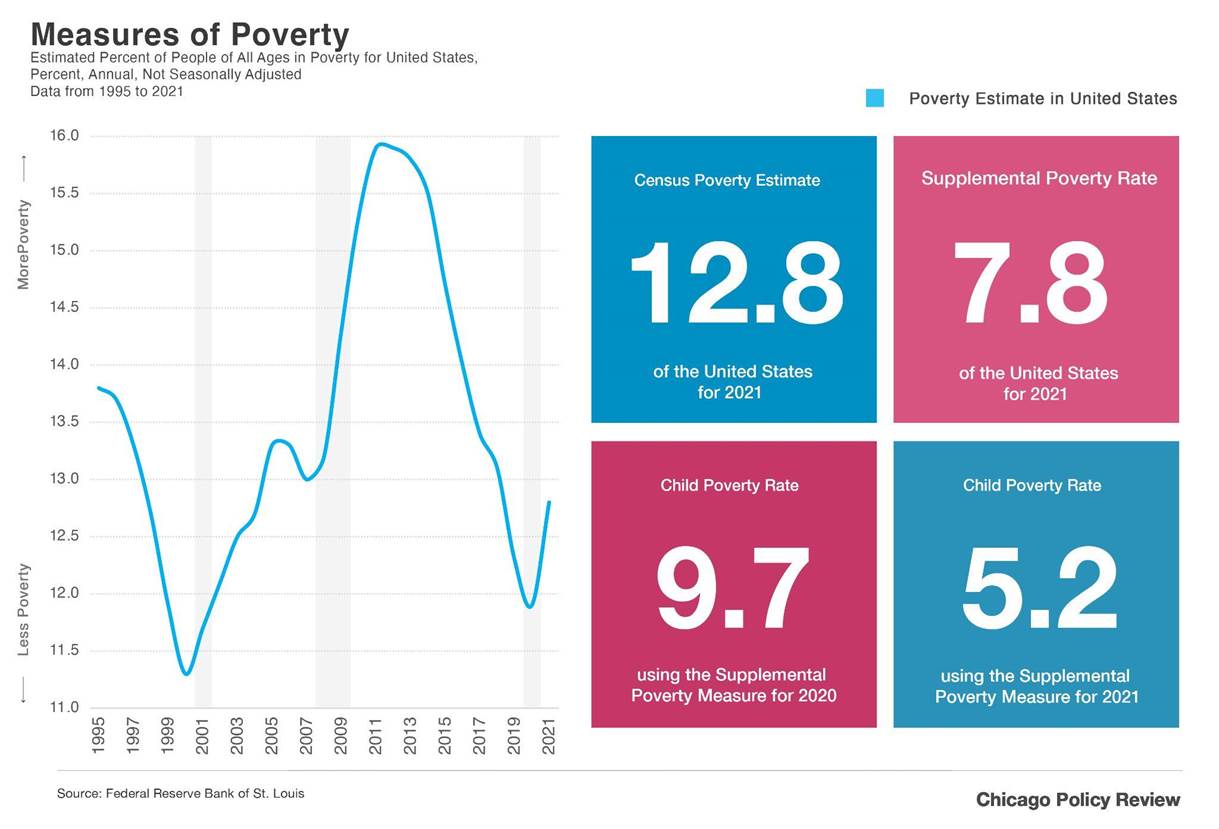

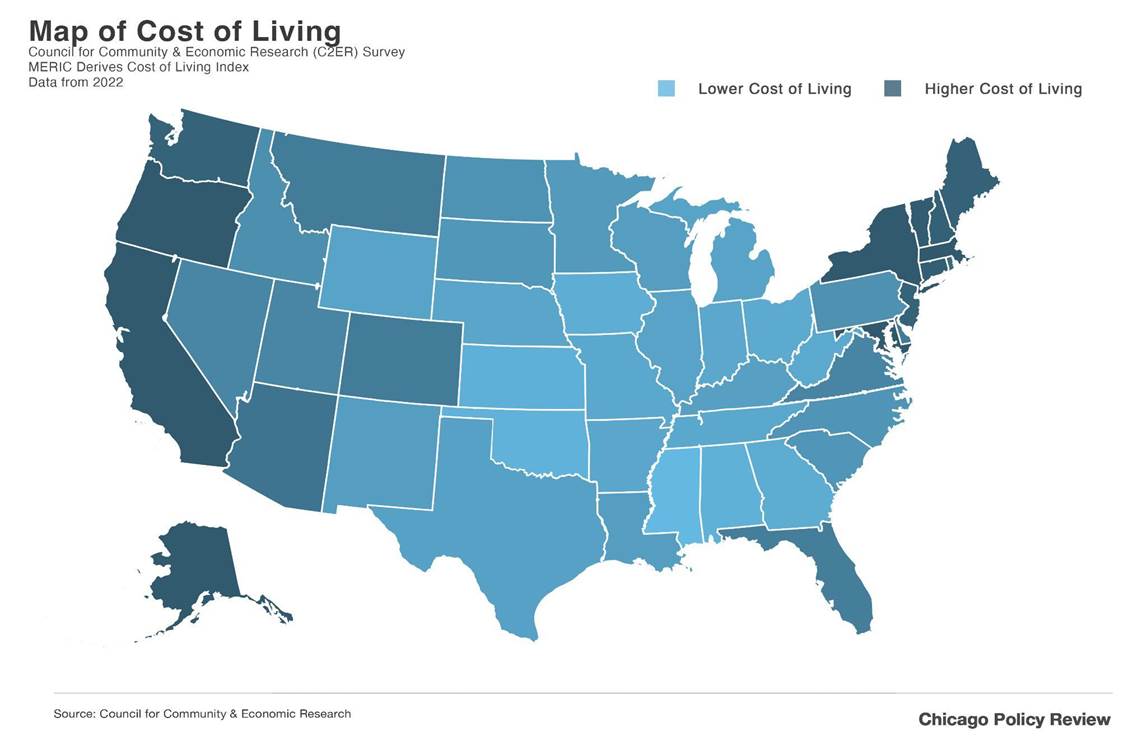

Noted poverty economist, the late Rebecca Blank, developed large portions of the Supplementary Poverty Measure, a more comprehensive measure, under the pretense that the Official Poverty Measure was inadequate. Currently, thresholds that the U.S. Census Bureau uses to officially calculate poverty are so low that various welfare programs already use multiples of the official poverty line in their determinations of benefits. For example, Obamacare tax credits are available for people earning up to quadruple the poverty line. The official poverty metric is calculated using fairly unsophisticated adjustments, such as family size and a limited definition of inflation, and is not adjusted to include differences in cost of living. The U.S. Census Bureau currently calculates a supplemental poverty measures to attempt to encapsulate the true breadth of poverty, but this measures does not apply to federal programs. While practical changes to fix these measurement problems may seem like common sense, achieving progress on niche technocratic issues proves difficult in a political environment that focuses more on controversy and fanfare than policy-specifics.

Proponents of the measure to comprehensively increase the poverty line argue that the current poverty measure causes millions to fall through the ever-growing eligibility holes in social safety net programs. While opponents argue that adding cost of living adjustments would result in an undue amount of people qualifying for welfare programs. Opponents also contend that reducing the welfare rolls has fiscal benefits, a key priority of the new House Republican Majority. However, significant research has shown that ignoring poverty and eligibility issues, as Republicans have effectively proposed, costs more than it attempts to save not cost-effective.

A more serious criticism of adjusting the poverty threshold is that scaling benefits with regional costs of living adjustments entrenches secondary effects: since most of the differences in cost of living is in housing and rent costs, scaling benefits would remove incentives to ameliorate underlying housing affordability issues. If those in poverty receive enough benefits to afford skyrocketing housing costs, then politicians may feel little need to address housing costs to begin with. Therefore, while updating the definition of poverty can be done relatively simply, policymakers must also address the asymmetries within the housing market before scaling benefits to avoid calcifying the housing affordability crisis.

There are multiple ways to potentially update the poverty line. Most simply, one could multiply the existing poverty line by some factor, which would align the measurement with existing commonly-used assistance eligibility qualifications. This would not affect eligibility for many programs and therefore likely be budget-neutral. Budget neutrality is crucial for limiting the amount of votes need to pass in Congress, making the bill much easier to pass. However, this change would increase the number of Americans considered impoverished, a controversial prospect for many rural lawmakers, who contend that their constituents are not in poverty but rather simply live in areas with lower costs of living.

Alternatively, the poverty metric could be adjusted to be more comprehensive and take into account cost of living. This would avoid potentially inaccurately counting rural American as impoverished and would provide a better understanding of true poverty levels. However, this change would result in many more urban Americans, who live in areas with high costs of living, qualifying for aid, thus requiring increased spending on assistance programs. Such fiscal implications may make such changes harder to pass in Congress, and rural lawmakers in particular may be unlikely to support such a measure that sends more aid to cities.

Metrics should not be allowed to rot, nor be politicized, and should acknowledge the obvious facts on the ground. At a minimum, poverty metrics should be flexible enough to recognize the basic reality that metropolitan areas are more expensive than rural small states. Poverty doesn’t look the same everywhere, and the tools the federal government uses to measure it must reflect that. Comprehensively scaling the poverty line relative to cost of living is plainly better policy, but the current congress is likely not interested in brokering ideal policy; and simply multiplying the current metric is much more politically feasible. Given the political reality, multiplying the poverty line seems to be the type of imperfect policy that we need right now. Not because such a policy is good or better, but rather because it can pass.