Conor Tomás Reed

This essay expands upon remarks I shared at the event “Poetics and Higher Ed Justice: The Role of Writers in the Struggle for a Freer University,” on May 5 at Wendy’s Subway, alongside sister CUNY educators Miriam Atkin, Makeba Lavan, Zohra Saed, and Meghann Williams.

It is our duty to fight for our freedom.

It is our duty to win.

We must love each other and support each other.

We have nothing to lose but our chains.

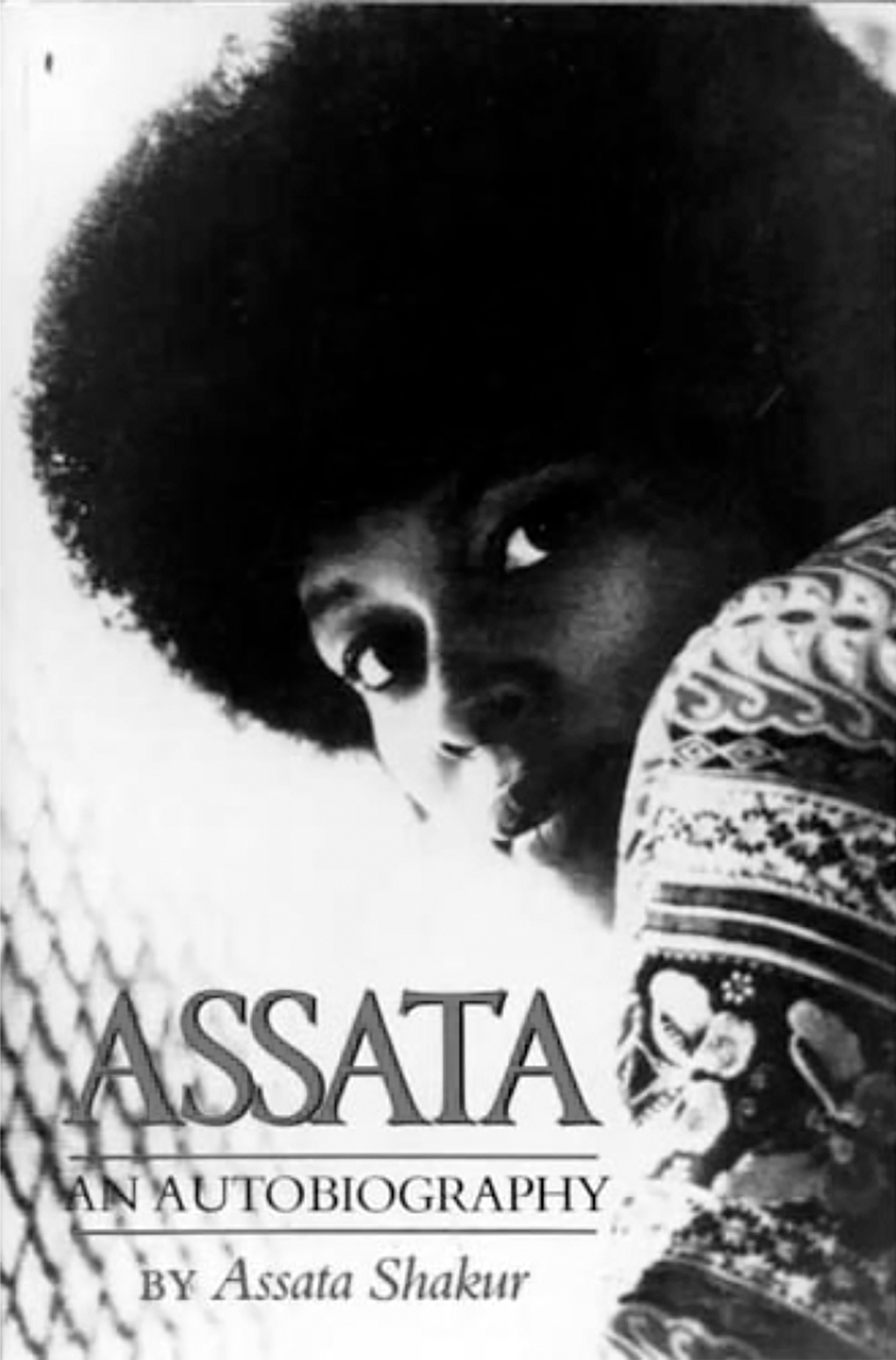

These words by the Black feminist revolutionary Assata Shakur have been chorused by countless crowds in the years since the Black Lives Matter movement has emerged. Nicknamed “Assata’s chant,” the phrases act as a street-speech talisman against police fear and liberal misdirection; they fuse Black and Third World feminist calls for radical care with the call for class warfare that concludes Marx and Engels’ Communist Manifesto. “Assata Taught Me” shirts and murals claim her as a godmother to the movement, and “Assata Shakur is Welcome Here” posters have begun to reappear from the time she was underground and in flight in the 1970s. However, as with any militant who can be selectively quoted and valued once they are converted into a larger-than-life icon, we risk her lessons becoming Twitterized and commodified.

These words by the Black feminist revolutionary Assata Shakur have been chorused by countless crowds in the years since the Black Lives Matter movement has emerged. Nicknamed “Assata’s chant,” the phrases act as a street-speech talisman against police fear and liberal misdirection; they fuse Black and Third World feminist calls for radical care with the call for class warfare that concludes Marx and Engels’ Communist Manifesto. “Assata Taught Me” shirts and murals claim her as a godmother to the movement, and “Assata Shakur is Welcome Here” posters have begun to reappear from the time she was underground and in flight in the 1970s. However, as with any militant who can be selectively quoted and valued once they are converted into a larger-than-life icon, we risk her lessons becoming Twitterized and commodified.

What can Assata Shakur teach us?

I first learned about her when I began studying at the City College of New York in 2006. The Guillermo Morales/Assata Shakur Student and Community Center’s red doors — emblazoned with a huge black fist clutching a pencil — were always open to textbook exchanges, campus and neighborhood organizing meetings, a community supported agriculture program, and radical study sessions. The space had been won through a 1989 CUNY student strike against proposed tuition increases, and served as a hub of activism, resources, and historical continuity between struggles. Assata and Guillermo had an enduring controversial relationship to City College from the time they had been students at the college (during the late 1960s and early 1970s) and their legacies as Black and Puerto Rican revolutionaries continued to threaten the conservative media, politicians, and the police, all of whom wanted this Center closed.

In May 2013, the FBI announced that Assata would be added to the Top 10 Most Wanted List (as the first woman, no less). Immediately afterwards, people made a social media call for “Assata Teach-Ins” to dispel the state’s myths about her. Free University-NYC hosted an event at Marcus Garvey Park in Harlem called “Assata Shakur’s Legacy and Lives of Resistance,” where CUNY/SUNY educator Nicholas Powers explored how Assata’s memoir might be used as a tool for liberation. First published in 1987, and reissued in 2001, lots of people have started to study this book again, drawn by the allure of Assata’s revolutionary life, which began with her association with the Black Panther Party in the late 1960s. She eventually went underground with the Black Liberation Army and survived a gunfire confrontation with the police at the New Jersey Turnpike in 1973. She was imprisoned for several years after the police shot her, eventually escaping to Cuba in 1979. She remains today in exile. Her memoir remains an invaluable record of Assata as a teacher-organizer; she tells the story of how she became a student, a community educator, and an “unreconstructed insurrectionist,” in the words of the movement scholar Joy James. Using narrative and poetry to tell her own story, Assata implicitly models how readers can commit their own lives to social change.

Certain aspects of the memoir offer lasting wisdom, and its strategic insights can be applied to our re-emergent struggles:

Assata spent her teenage and young adulthood years across New York City — Harlem, Lower East Side, Queens, Upper West Side — in which she embedded extensive roots and cultivated an intimate familiarity with the city that she sought to help transform.

Assata was not born a revolutionary, but became one along a wayward path of experiences with various Black radicals, reformists, and conservatives. As she became more seriously involved, she was mentored by African student communists and Black American student radicals in New York City, and Asian, Black, Chicano, and Native American radicals during a short Bay Area trip in 1969.

Assata entered the Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC/CUNY) in the late 1960s, and she rapidly became immersed in Black liberation work through contact with Golden Drums, a campus group that created events with Black studies curricula and activities, even as they simultaneously demanded that the college formally implement similar programs. They organized lectures about Black histories, through which Assata first learned about Nat Turner and others who actively resisted their enslavement. Golden Drums nurtured a thriving cultural scene, with bridges between higher education, youth, and community knowledge. They hosted concerts, plays, poetry readings, dancing, drumming, arts and crafts, in addition to (re-)teaching history, reading, and math.

In the late 1960s, Assata joined the Black Panther Party, and was instrumental in the Harlem free breakfast program and free health clinic when she transferred to City College. Education was a central element of the Black Panther organization, and Assata outlines pedagogical methods that can bridge radical learning between childhood and adulthood as well as informal neighborhood programs and formal educational institutions.

Assata left the Black Panther Party over crises in leadership and direction during a time of vicious state repression, but she remained connected with several comrades, and eventually went underground with the Black Liberation Army, an offshoot of the Panthers. After her 1973 New Jersey arrest, she released the statement “To My People,” on July 4, 1973. It was broadcast on hundreds of radio stations and published in movement newspapers across the country. It is from this statement that the now-famous Assata chant is excerpted. Even if street chants can’t be paragraphs long, let’s return to this statement as a way to root our current focus on Black liberation as a precondition towards full mutual liberation, so that the shortened chant can manifest even wider meaning each time we say and hear it. Assata writes,

Every time a Black Freedom Fighter is murdered or captured, the pigs try to create the impression that they have quashed the movement, destroyed our forces, and put down the Black Revolution. The pigs also try to give the impression that five or ten guerrillas are responsible for every revolutionary action carried out in amerika. That is nonsense. That is absurd. Black revolutionaries do not drop from the moon. We are created by our conditions. Shaped by our oppression. We are being manufactured in droves in the ghetto streets, places like attica, san quentin, bedford hills, leavenworth, and sing sing. They are turning out thousands of us. Many jobless Black veterans and welfare mothers are joining our ranks. Brothers and sisters from all walks of life, who are tired of suffering passively, make up the BLA.

There is, and always will be, until every Black man, woman, and child is free, a Black Liberation Army. The main function of the Black Liberation Army at this time is to create good examples, to struggle for Black freedom, and to prepare for the future. We must defend ourselves and let no one disrespect us. We must gain our liberation by any means necessary.

It is our duty to fight for our freedom.

It is our duty to win.

We must love each other and support each other.

We have nothing to lose but our chains[.]

Assata then names the friends and comrades that the FBI’s Counter-Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO), police, and prison authorities had murdered within the last several years—Ronald Carter, William Christmas, Mark Clark, Mark Essex, Frank “Heavy” Fields, Woodie Changa Olugbala Green, Fred Hampton, Lil’ Bobby Hutton, George Jackson, Jonathan Jackson, James McClain, Harold Russell, Zayd Malik Shakur, Anthony Kumu Olugbala White — and ends the address with the words, “We must fight on.”

By framing the Black Liberation Army as a perpetual fighting force that will continue to exist until Black freedom is fully actualized, and by including people from “all walks of life” as its members, Assata defines the group’s ongoing purpose and invitation to participate in the most expansive terms possible. In this way, Assata articulates a crucial strategic pivot for Blackness and revolutionary activity, which anarchist Black Panther Ashanti Alston further elaborated by noting that “being Black not so much as an ethnic category but as an oppositional force or touchstone for looking at situations differently.” Moreover, as a teacher-organizer writing these words from prison, Assata also urges us to reconsider COINTELPRO as a means by which the U.S. government surveilled, disrupted, encaged, and murdered teachers and students. The work of state counter-intelligence literally meant demolishing the Black Panthers’ freedom schools approach, which was gathering a broad audience among poor and radicalizing people of all colors.

UNITED STATES – JANUARY 29 – (Photo by Frank Hurley/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

Although we may have lost the intensity of the historical moment, it’s difficult to overstate how widely this imprisoned CUNY student and community educator was known and defended during the 1970s. City College poet-educators followed her case closely. Adrienne Rich kept notes on Assata’s case in her archives. June Jordan read in 1977 at a benefit for Assata alongside Jayne Cortez. Audre Lorde kept a poem written by Assata in her archives, and in turn wrote the 1977 poem “For Assata” in her collection Black Unicorn, in which she says “I dream of your freedom / as my victory / and the victory of all dark women.” The most prominent Black Studies publication of the time, Black Scholar, featured a 1978 essay that Assata wrote while in Rikers Island prison, “Women in Prison: How We Are,” alongside work by Angela Davis. By the time of Assata’s prison escape, freedom fighters worldwide were deeply inspired by her, even as U.S. movements suffered during the abysmal Reagan years.

I hope that in CUNY and NYC we can still proclaim Assata Shakur as one of our own.

The U.S. government relentlessly attempts to track her down, and Assata has likened their tireless pursuit to a modern-day fugitive slave hunt. In October 2013, the CUNY administration (and, presumably, the NYPD and FBI), seized the Morales/Shakur Center and its belongings — including an invaluable trove of movement archives — using, as a pretext, retaliation against organizing campaigns to oppose the creeping militarization of CUNY. In Spring 2015, Cuba and the United States entered a diplomatic “normalization” process, during which time Assata’s exile briefly risked being jeopardized. Her continual Black freedom matters. I invite us to study her memoir and other writings to apply their pedagogical lessons today, both inside our classrooms and outside across our communities. I urge us to connect the struggle for free education and free poetry with the struggle to break down prison walls and abolish the police. And finally, I ask that we welcome Assata’s words of “Affirmation” in these turbulent times:

I believe in living.

I believe in birth.

I believe in the sweat of love

and in the fire of truth.

And i believe that a lost ship,

steered by tired, seasick sailors,

can still be guided home

to port.

I see you don’t monetize gcadvocate.com, don’t waste your traffic, you can earn extra bucks every

month with new monetization method. This is the best adsense alternative for any

type of website (they approve all sites), for more details simply search in gooogle: murgrabia’s tools

I see you don’t monetize gcadvocate.com, don’t waste your

traffic, you can earn additional cash every month

with new monetization method. This is the best adsense alternative for

any type of website (they approve all websites), for more

info simply search in gooogle: murgrabia’s tools