Maria Heyaca

On 17 September, the Governor of Puerto Rico declared a State of Emergency in anticipation of Hurricane María, and the storm pummeled the island three days later. The devastation was huge: the water, electricity and communications infrastructure was wrecked; houses blown away; flooded bridges and roads; trees downed and crops destroyed; loss of animals, and a vast death-toll. The aftermath was peculiar: after endless hours of hurricane winds bashing and banging doors and windows, time stood suspended in a profound calm. The initial impulse was to reaffirm life through contact with others. “We are alive,” shouted our neighbors, waving from balconies and rooftops.

On 17 September, the Governor of Puerto Rico declared a State of Emergency in anticipation of Hurricane María, and the storm pummeled the island three days later. The devastation was huge: the water, electricity and communications infrastructure was wrecked; houses blown away; flooded bridges and roads; trees downed and crops destroyed; loss of animals, and a vast death-toll. The aftermath was peculiar: after endless hours of hurricane winds bashing and banging doors and windows, time stood suspended in a profound calm. The initial impulse was to reaffirm life through contact with others. “We are alive,” shouted our neighbors, waving from balconies and rooftops.

Almost immediately, communities self-organized to clear heavy debris from driveways and roads. Decades of austerity measures had greatly reduced the personnel and machinery available for emergency relief to municipalities and public companies like the Electric Energy Authority, and most people never saw the road clearing brigades the government boasted about. The only contact with the world outside the neighborhood was through radio, which reported the scale of the disaster, warned that recovery would take a long time, and allowed people to verify their loved ones’ safety.

I travelled to New York soon after the hurricane, where I was startled by the degree of international attention, but even more so by the narrative: My suspicion about the rhetoric surrounding the catastrophe grew stronger when I saw a flyer for a fundraiser to “help the PR refugees.” A refugee is someone who is forced to cross an international border because of persecution, war, or violence. None of this applies to Puerto Ricans. When the government still speaks of a “humanitarian crisis” two months after the event, all the while masking its negligence, I have to insist on the importance of interrupting this manipulation of humanitarian discourse. It cynically exploits human suffering, and hides the real “crisis,” throwing both locals and the diaspora into a panic and stimulating the emptying of rich rural lands. As I leave New York, a sweet, compassionate woman asks: “Are you going back to PR?” “Yes!” I respond with joy, anticipating my return to beautiful Camuy. Tears in her eyes, she replies: “God bless your heart.” That was the moment this report was born.

Like the Three Wise Men

Survivor testimonies of the disaster and its aftermaths are heart wrenching. The family of one cooperative worker, including children and elders, had to swim and take refuge in the forest for five days after their house was swept away by the river. Nobody came to their rescue. Some had to live with the corpse of a family member for days while searching for an official to certify the death. Hundreds of corpses came to the surface after a cemetery flooded in Lares, potentially contaminating streams that feed into San Juan’s water reservoirs. Veterinarians from Quebradillas were unable to assist Guajataca communities because of the stench of rotten animal corpses.

I recorded some of these testimonies while waiting in unending lines at the gas station, the bank, the supermarket, and the bakery, which became spaces to strengthen community bonds and to share experiences. A week into the hurricane, a clear contrast between the official version and what people were experiencing on the ground began to take shape. Why are thousands of tons of food stuck in San Juan’s ports while supermarkets lay bare in the island? How come there is a gas shortage in such small territory?

These long lines also offered the great spectacle of the corruption that lay beneath so much suffering. On the fourth day of looking for gasoline, we ran out of gas. We had just enough to get in a mile-long line. The line moved more or less speedily as we pushed the car onward. Then, two new lines suddenly formed: one for “public servants” (healthcare workers, teachers, press, and police) in which none of the cars had official plates and mainly gathered friends and relatives of “public servants,” and a second one for “politicians,” which was odd considering the local government was for the most part closed. Behind us, in the people’s line, a woman sought gas for her brother, who relied on a machine to breathe. She was unable to get gas. At 9pm that Wednesday night, the owner of the station asked us to go home, yelling “there is no gas until Friday.”

Early next morning, asleep in my stranded car, I woke to a knock on the window. “Maria, hurry, you need to document this,” I was told, as I watched people arguing with a policeman while demanding that the station distributed the gas it had stashed away. I witnessed the infuriated policemen threatening: “I could arrest you all right now. Just wait till the National Guard takes over. They shoot first, ask questions later. Some of you here are gonna end up dead.” I watch some policemen park their car, take containers out of the trunk, and fill them with what, according to my neighbors, is gas to be delivered to the rich so they could sleep with AC. Turns out there was indeed gas at the station; this is the value of life in post-Maria Puerto Rico: gas for the rich so they can run their ACs, no gas for those on life support in the people’s line. In the days that follow, stories that involve police officers diverting supplies and power plants multiply. Today, it is an open secret.

The incident at the gas station took place under a curfew in effect since 20 September: “our citizens are under grave risks, especially at night,” the executive order states, a sentiment many people endorse. In the racist, anti-poor fantasy of some, masses of youth from residential projects would come out under the cover of darkness to rob people’s homes, which also explains why public housing projects were electrified so quickly. Yet never once did I witness “insecurity” in the darkness. What I did see was a brazen pilfering of public goods by the state apparatus at the gas station. Whether by design or not, the curfew created perfect conditions for the trafficking of vital supplies.

It is common in PR for elected officials and their executives to favor their constituencies in providing relief, and this is key to understanding the territorial logics of the “humanitarian crisis.” A few days after the hurricane, for instance, a rumor came down from the central highlands: Utuado is destroyed and militarized. Images of the municipality which was declared a zone of major disaster filled mainstream media and social networks alike. “Utuado forgotten by time,” declares Univision, with the picture of a young lady bathing with spring water by a road. The image of a military truck or a helicopter delivering supplies to residents smiling back at officers in gratitude went in tandem with these apocalyptic prophesies. It was even the cover of the most hegemonic newspaper. The message: the great US Army will save us.

In the words of a renowned activist: “A month after Maria they were all over: businesses, city hall, main avenues. Helicopters landed on the road holding up traffic to deliver food boxes. Supposedly they were working on opening roads. The strange thing is they work with no equipment: they go around but do not carry supplies, tools, machinery or equipment. Road clearing brigades with no equipment? This rather looks like a display of force.”

According to FEMA, there are over fifteen thousand federal employees in PR. More than eighty percent of them work for the Department of Defense, and four thousand are military personnel. This is in addition to the National Guard, which responds to the Governor. There may be more soldiers per capita in PR today than in Iraq after the US invasion. A substantial number of these military personnel are in Utuado. Some people think it’s a plot to damage the mayor´s reputation: “He is a PPD in a PNP town. His office is controlled by the military. They got rid of him. People are ok with the arrival of the military. Lots of vets live here.” Irizarry Salvá is the first PPD mayor in twenty years, and right before Maria he announced his Facebook account had been hacked.

While the response to the crisis in Utuado was heavy militarization, some communities on the other hand have not received any military help whatsoever. José Felipe Gonzalez and her partner Felisa Collazo are recognized scholars of Antillean birds. He coordinates the arrival of supplies to Barrio Arenas, where they live. The river flooded during the storm and the bridge that connects Arenas to the main road collapsed. The isolated residents organized and survived without external helps and rebuilt the bridge. José smiles while saying: “The military are like the Three Wise Men. They come at night and you don’t see them. The difference is they do not leave gifts.”

A Military Hospital In a Public University?

“They are going to open a military hospital at the university,” a student tells me. A few days later, someone approached three people in medical attire to ask what was going on at the university. The “nurse” didn’t respond and eventually reported the incident to the university authorities, who began trying to identify the person a few hours later. Allowing the military on campus is a massive threat to the Utuado students movement, which was the great surprise of the last UPR strike. The movement consolidated so quickly and so well that three of its leaders were penalized. There were also attempts to link the students to a mysterious burning of some documents, which might have paved the way for an FBI intervention, and inviting the military on campus obviously jeopardizes the movement’s capacity to rebuild and reorganize.

The Provost of the university has said that the hospital will be managed by a US medical association, and will offer free services to people in need and strengthen the university’s role in the community. Yet there is little transparency or clarity about the relationship between the medical teams and the US military. Team Rubicon, for instance, which recently visited communities in Utuado, was primarily composed of army veterans. All of them were white men who had no working knowledge of Spanish, and they avoided answering the questions of local volunteers and physicians.

In such murky contexts, it is important to recall that army officials have faced accusations of sexual violence in several countries, and incidents of sexual harassment involving officers deployed in PR only confirms this trend. Militarization also often increases trafficking, an alarming thought in light of the high levels of unemployment amongst young women. Considering that the island has historically been a focal point of unethical medical experiments—such as the mass sterilization of rural women in the 1950s—it is important to continue to be skeptical about the use and abuse of medical authority and army coercion in PR today.

Humanitarian Crisis or Disaster Colonialism?

Shrewd North Americans see clearly that the hurricane, which ruined the entire country, accelerates the economic penetration of the United States into Puerto Rico

Pedro Albizu Campos, February 1930

The plan is to empty the country of working class (poor) people and fill it with tourists/investors, clear the way to mining in the mountains, keep filling the coasts with hotels and restaurants that no normal local will be able to pay.

Shaisa Soto Ruiz, young mother, peasant, and Utuado resident, November 2017

While mopping the floor with rainwater, I hear the radio announce: “Hillary Clinton urges Trump to send the Army to PR.” “We are finished,” I thought. On 24 September, Hillary Clinton tweeted: “Pres Trump, Sec Mattis, and DOD should send the Navy, including the USNS Comfort to PR,” echoing a Change.org petition started by Rick Trilsch, a Clinton supporter and Vice President of Finance and Administration for Western Resource Advocates, which is portrayed on its own webpage as “advocating for the West’s transition to clean energy”—in the exact same terms the Democratic Party has been pushing in Latin America. When the Democratic Party—especially Hillary Clinton—militarizes Latin America, the motivation is always to loot our common resources. This time, the excuse is changing the energy matrix: replacing fossil fuels (which the economy is almost exclusively dependent on currently) with renewable energy.

On 27 September, representatives Gutierrez and Crowley sent a letter to the Secretary of Defense requesting a meeting about the military’s role in PR. In the letter, they mention “the heroic support” of the army in Haiti and New Orleans, but entirely ignore the accusations against the Clintons by Haitian activists, who insist that the Clintons enriched themselves with the reconstruction funds. The majority of the $9.04 billion USD international funding went to the UN and private contractors; only 0.6 percent went to local organizations. After Katrina, similarly, black low-income communities were displaced and gentrified, and Brad Pitt today builds profitable eco-friendly housing in the Lower Ninth Ward that the people who originally lived there can no longer afford.

Honduras, however, is perhaps the most illustrative example of what could be coming to PR. After the coup against Zelaya (which was sponsored by Hillary Clinton’s State Department), areas rich in natural resources were militarized and several licenses to exploit rivers were granted. (Water is one Utuado’s most precious treasures.) These licenses were approved in record time, and without carrying out any environmental impact assessments.

A recent administrative order in PR, meanwhile, waives the environmental impact assessment for the “enlargement, rebuilding, and rehabilitation” of coastal areas at risk from floods. To Humfredo Marcano, a biologist working for the US Forest Service, “the idea of “disaster” creates the perfect conditions for loosening permits for the construction industry.” This idea of “enlargement” creates a grey zone and has the environmental movement concerned. “What constitutes an “enlargement”? Who monitors whether some construction work is an “enlargement” or not?” Marcano continues, “A hotel company could expand its facilities alleging “enlargement” and not giving environmental activists or the community enough time to react.”

Recent official statistics suggest a sharp population contraction. The “exodus” started with the catastrophic images which the US press reproduced, as residents brought older or sick relatives to the US. This created the material for the first headlines in the local, hegemonic media stimulating the wave. Thousands then left in “free” flights. Material and employment loss, and the closing of schools have also encouraged the “exodus.” According to the people who took refuge in local schools, FEMA is trying to displace them to the US, claiming there are no spaces left for temporary housing in hotels.

Maria did not cause this massive migration; it accelerated it. The island has been losing population for decades. The roots of the “exodus” go back to decades of colonial looting and local corruption. What is alarming, however, is that the government seems willing to take advantage of the present moment to push for the Board’s agenda, which could include the privatization of the Electric Energy Authority. The case of the schools reveals some of the hidden ways in which this “humanitarian crisis” has played out. Before Maria, Secretary of Education Keleher made it clear that she would please the Fiscal Control Board with the privatization or closing of schools, which became difficult in face of a solid popular resistance. The hurricane is a wonderful excuse to comply with the Board. Many schools are still closed, while others function as refuges. Some families organized to occupy schools and demand their opening. Others migrated so their children don’t lose the school term. “The decline in the number of enrolled students is noticeable,” comments Juan Jiménez, Utuado teacher. Since María, more than 6,000 children left PR.

Undoubtedly, the “exodus” promises good deals for the hotel industry and extractive companies, which could benefit from such an emptying of the territory by buying land at bargain prices. In addition to water, Utuado is rich in minerals and has been one of the most important municipalities in the fight against open-pit mining. Recently, the Rebuild Puerto Rico economic summit took place in the luxurious Condado Vandervilt. Roughly 200 people attended, including businessmen, the FEMA Director, and the PR Governor, whose speech was particularly intriguing: “We know you have good connections in Washington. Help us get the appropriate funding.” Time will tell if those resources will be channeled towards people or towards the companies that seek to get rid of them.

Going back to Honduras, hundreds of women with children from the Black-Indigenous Garífuna communities migrated to the US in 2013. Like Puerto Ricans today, these women were labeled “refugees,” and the US media called it a “humanitarian crisis.” Since this “exodus” began, it has grown increasingly evident that this Garífuna land is being targeted for “development” by Canadian companies, who want to turn their ancestral territory into hotels and other profitable tourism enterprises— plans which don’t, as Shaisa´s wise words anticipate, include the locals.

I was about to send this article to my editor when my cell phone buzzes with a text message: The Clinton Foundation is coming to Puerto Rico.

La Granja Is Still Here, The Fight Continues

La Granja community in Utuado owes its name to a farm once owned by the UPR, which conceded the land to the government. That’s how the community was born. Today roughly 270 people live in La Granja, scattered between 40 families. According to Yajaira Pagán, granddaughter of Juan Cruz Rivera, the first Utuado shoemaker: “families used to be larger. Fathers, sons, grandfathers, uncles, all lived together. Back then, farm labor was the primary source of income. Farm workers cultivated coffee, oranges, grapefruit, lemon plantains, and bananas in local farms, in addition to cultivating their own crops. This changed around 1995, with the epidemic of people migrating because they could not get work, but as our guide Juan remarked, agriculture in Utuado held on strong because of the people of La Granja.

These days many people supplement their income with construction and domestic work, but work is hard to find and many young people are migrating. Residents are mostly adult, and often depend on help from the government. “We changed agriculture for food stamps and we came out losing?” I ask Yajaira. “Yes that’s exactly it. ”

When she was young, Yajaira escaped to play in a small creek, now buried under a cement road built 25 years ago. That image that so horrified the press, of Utuadians washing in the river, is affectionately remembered by families of La Granja. Water is one of La Granja’s defining characteristics. “We got all we need,” states Juan. It belongs to the community “because it comes from nature. We would not agree to its privatization.” In addition to water, the mountain is rich in bronze, limestone, and calcic rock.

Maria hit hard. Nilda Torres River’s testimony is harrowing. The creek came in through the back and out the front door. Her house is now covered with mold and has been declared inhabitable. But Nilda and her husband, who sleeps in a mattress propped on top of chairs, have no place to go. There is no electricity nor any water, and she was forced to send her grandson to the US. “My grandson, my life, was taken from me, this is not living!” she screams in desperation. Nilda and her husband take sedatives in order to sleep at night, “in case a landslide buries us, we’ll die without feeling a thing.” Nilda applied for disaster relief from FEMA. Her application was rejected because she has insurance. But the insurance people are nowhere to be found. Some years ago, some of La Granja houses were placed in “red zone,” meaning they were susceptible to landslides. The municipality bought most of these houses and moved residents to the town of Quitín. Nilda tried to sell her house but the municipality refused.

My journey through La Granja was made possible thanks to the Mutual Help Centre of Utuado (CAM-U), which is part of a network of self-organized community-based initiatives, with no political affiliation. They are doing incredible work in community support and reconstruction in various municipalities across the country. Some of their activities have included community soup kitchens, solidarity brigades in different farms, community health clinics, theatre shows for children, and the distribution of vital items such as solar lamps, mosquito nets, and tarps.

Jurrisán Alabrrán Rodriguez, an enthusiastic and civic-minded young woman, resident of La Granja, and employee at the UPR, served as the liaison between La Granja community center and the CAM-U. They co-organized two workshops in the center. The first distributed water filters and 3000 water purifying tablets. The second offered legal assistance by the director of an Inter-American University free clinic, in which the seamy underbelly of FEMA’s record came to light. Mayra, the director of the center, is full of dreams. This center is one of the hundreds of collective spaces that Maria helped to strengthen. “When I lower my arms, I find angels,” she shares, thinking about the dedicated work the CAM-U is doing. “The hurricane came to help us grow spiritually. While we have everything, we are ungrateful. It has taught us to share and it has brought unity, which is the most important thing,” says resident Vivian, who lost everything, with a smile. Her husband William, is an artisan and a farmer: “agriculture’s his life. He dreams of his machete.”

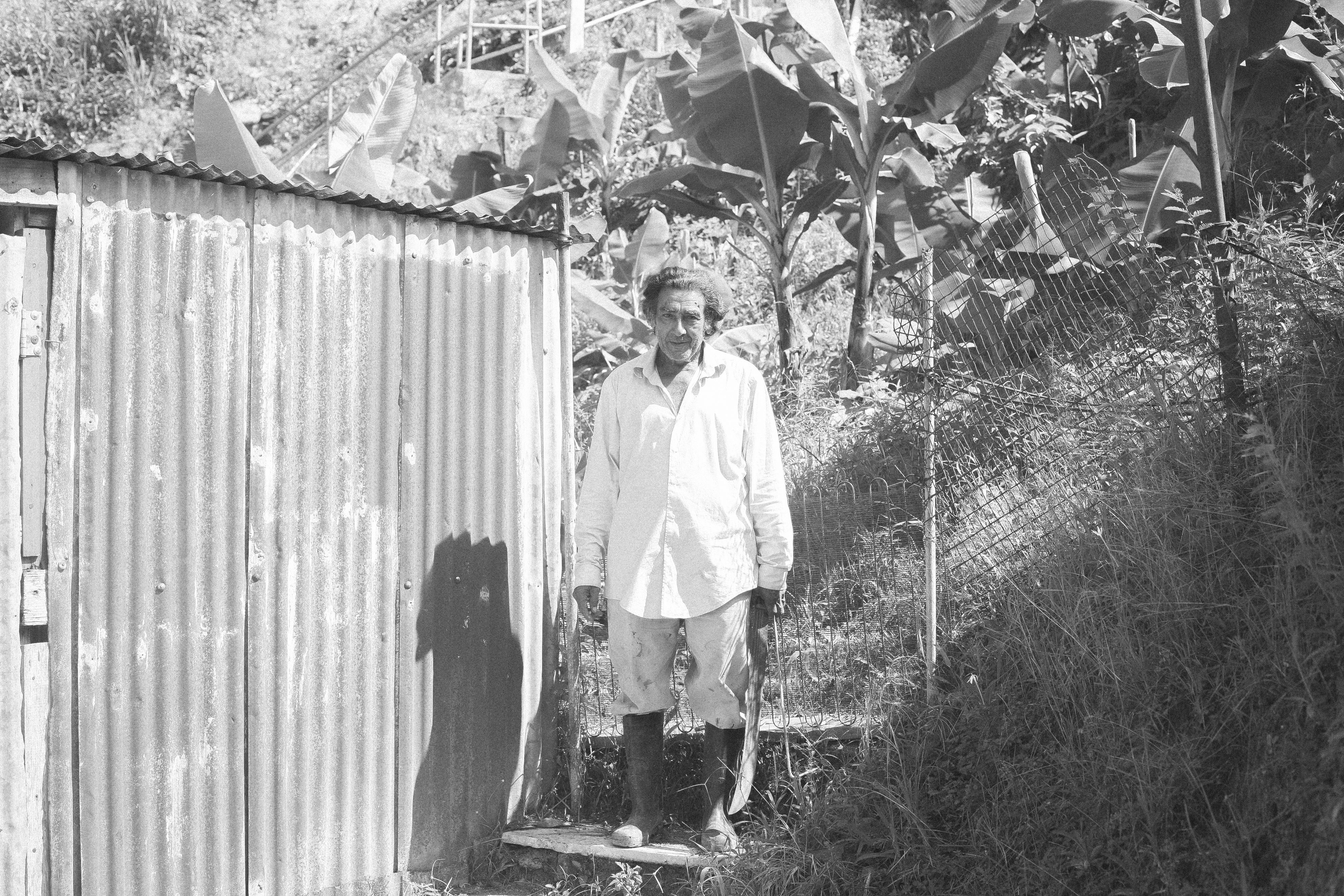

The photographs in this article are of the residents of La Granja and Arenas. The images aim to counteract the exploitation of suffering so loved by the hegemonic press. These are not pictures of destruction but faces of the sons and daughters of the highlands, standing triumphant.

We’re here, and we’re not going anywhere.

How to help

1. Avoid the expressions “refugee” and “humanitarian crisis.” Speak instead of a possible plan to displace the population

2. Do not focus your attention on the city: the highlands are threatened by green capitalism

3. Spread word about the reconstruction work carried out by community-based organizations that are not affiliated to political parties, NGOs, or foundations.

4. Donate water filters, solar lamps, mosquito nets, tarps, organic seeds, and farm tools. You can contact us in the AELLA office at the Graduate Center or send us an email at popolvuhitinerante@gmail.com

5. Help us stop the Clinton foundation from disembarking in Puerto Rico. They have their offices in Harlem

6. Organize a research group and survey Puerto Ricans migrating to the US. Try to determine which town they came from and whether they left voluntarily or were somehow persuaded. Contact us with the results to share vital information with grassroots activists: every testimony makes a difference

7. Demand the de-militarization of the highlands by organizing a protest or contacting your local representative

8. Speak out against Trump’s racism, but do not believe in the Democrats’ green energy discourse. It is a mask to sack our common goods

Hello fantastic blog! Does running a blog such as this take a great deal of work?

I have absolutely no understanding of coding but I had been hoping to start my own blog soon. Anyhow, should you have any ideas or techniques for

new blog owners please share. I know this is off subject nevertheless I just had to ask.

Appreciate it!

This is a great tip especially to those fresh to the blogosphere.

Simple but very accurate information… Thank you for sharing this one.

A must read article!

I am not very wonderful with English but I line

up this real easygoing to read.

Hello, I think your website might be having browser compatibility issues.

When I look at your blog site in Firefox, it looks fine but when opening in Internet Explorer, it has some

overlapping. I just wanted to give you a quick heads up! Other then that, awesome blog!

Pingback: Decolonizing the Disaster: Defending Land & Life During Covid-19 | Political Theology Network