Hillary Donnell

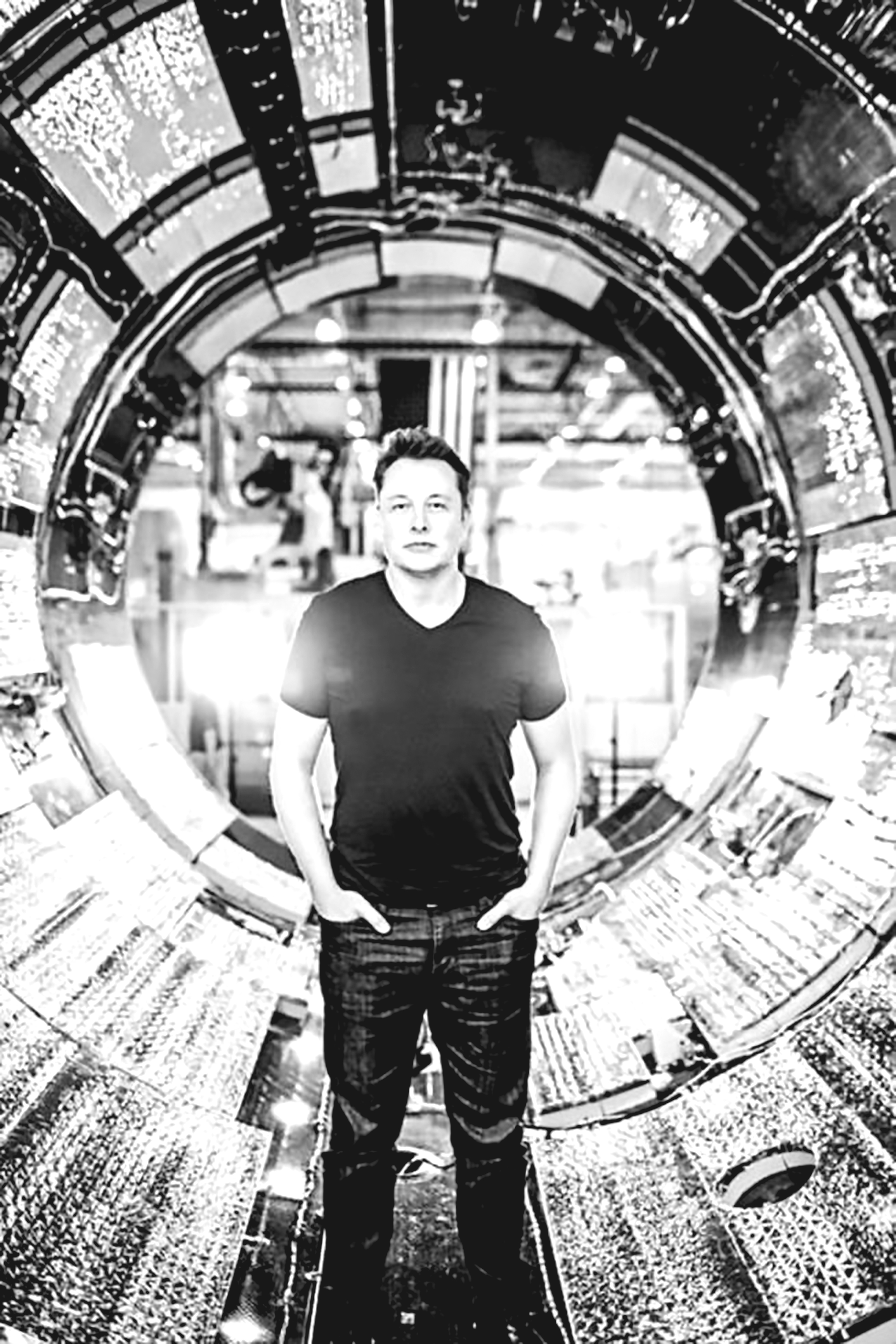

There’s something fascinating about the scintillating mythos that American society has created of the man behind PayPal, SpaceX, The Boring Company and Tesla. His rise to prominence as America’s innovator-in-chief has been exalted by the growing cult of personality that surrounds him. There are YouTube channels devoted to figuring out the source of his genius, tracking his eating and sleeping habits, while devotees excitedly retweet clips of each fiery SpaceX launch and fawn over his jeans-wearing, billionaire next door persona. But for all the Musk fans, there is a growing cadre of Musk skeptics who are uncertain about the future that Musk wants to sell us. Perhaps, though, it is those millions who hold Musk up as an idol, a harbinger of hope for the future, whose obsession tells us the most about ourselves as Americans. Musk-lovers reveal what we revere: entrepreneurship, innovation, rule-breaking, conquering new frontiers. But there’s plenty about Musk’s millennial charm and the future he promises that merits closer scrutiny.

There’s something fascinating about the scintillating mythos that American society has created of the man behind PayPal, SpaceX, The Boring Company and Tesla. His rise to prominence as America’s innovator-in-chief has been exalted by the growing cult of personality that surrounds him. There are YouTube channels devoted to figuring out the source of his genius, tracking his eating and sleeping habits, while devotees excitedly retweet clips of each fiery SpaceX launch and fawn over his jeans-wearing, billionaire next door persona. But for all the Musk fans, there is a growing cadre of Musk skeptics who are uncertain about the future that Musk wants to sell us. Perhaps, though, it is those millions who hold Musk up as an idol, a harbinger of hope for the future, whose obsession tells us the most about ourselves as Americans. Musk-lovers reveal what we revere: entrepreneurship, innovation, rule-breaking, conquering new frontiers. But there’s plenty about Musk’s millennial charm and the future he promises that merits closer scrutiny.

Last year at a Halloween house party in Brooklyn I was making casual conversation about Musk with anyone who would listen. I was decrying the supposed achievements of Musk’s companies, attacking the low hanging fruit, Paypal, of one of Musk’s first successful companies. I was arguing that while Paypal and now Venmo, which Paypal acquired in 2016, has definitely made it easier to pay your roommate your share of the rent, they have done nothing significant to address modernity’s most pressing social problems, wage-inequality, gun violence, racial segregation, to name a few juggernauts exacerbated by persistent state disinvestment and neglect. A bystander unimpressed by my pontificating exclaimed, “But you have to admit that he has some really good ideas!” Clearly irritated that I was missing the point of entrepreneurial activity, they continued, “And the thing is, he just goes for it. He actually makes them happen.”

Given the urgency and emotion in this person’s tone, I backed off, sensing that just one more stab at Silicon Valley’s savant might spoil the celebratory mood. Later I considered how this person’s reaction betrayed just how much of ourselves we see in Elon. My interlocutor seemed upset not only because I was criticizing Musk, but because I was taking shots at the eroticized spirit of entrepreneurship that he embodies. This is the entrepreneurship that the American collective conscious associates with Manifest Destiny, cowboys, the space race, and a few centuries of American folklore. It’s what we believe makes us truly American and Elon Musk is the kind of guy people admire, if only for the boldness he demonstrates in dreaming up an idea and seeing it come to life. And while a twinge of his South African accent remains, we’ve been more than happy to adopt him, thanks to his uncanny encapsulation of the American spirit. He’s telling us to go into the wild, dream something up, and make happen with nothing but our wit, a shoestring, and some tape. He’s our John Wayne, Buzz Aldrin, Steve Jobs, our Tony Stark, all rolled into one.

But what have we missed while gazing at Musk with our rose-tinted glasses? What makes his ideas especially attractive to modern consumers, I would argue, is the subtle appeal to the “common good” embedded in the marketing of his products. Which would be fine, if that’s what his products were actually providing. Rather, “doing good” has become a veritable dog-whistle for those seeking some absolution with their consumption. This appeal is what enabled Musk’s companies to garner billions in public funds and become models for how we conceive of sustainable futures.

As the modern consumer has discovered, living with worlds of consumption at one’s fingertips does not come without a dark side. The globalization of production processes along with the rise of communication technologies means we have more insight than ever about the horrors that characterize the assembly of our iPhones. Abysmal wages, unsafe working conditions, enormous environmental costs. A natural consequence is that consumers begin to have an emotional response to the fact that their consumption is tied, however remotely, to the extreme violence of globalized production. Capitalism’s countermove? Commodify that response. The marketing strategies of SpaceX, Starbucks’, Tom’s and countless other businesses have been tweaked to tap the market created by our guilty conscience. Consider seals of approval vouching for far-off sustainably sourced worker-owned coffee plantations, the advertisement for a pair of shoes that goes to the nameless child in need for every pair you buy, the app that tells you exactly who was harmed and where in the making of that H&M hoodie. In each of these models the conscious-consumer is assuaged by a degree of control that they are given over the harm that they cause through their consumption. The ethical consumption craze is a pervasive marketing technique, ensuring that all kinds of goods and services must make some mention that their products are doing their part to chip away at a social problem. By tweaking the business model to incorporate and assuage consumer discomfort, globalized production processes transform the very act of purchasing into the promotion of social welfare.

As the modern consumer has discovered, living with worlds of consumption at one’s fingertips does not come without a dark side. The globalization of production processes along with the rise of communication technologies means we have more insight than ever about the horrors that characterize the assembly of our iPhones. Abysmal wages, unsafe working conditions, enormous environmental costs. A natural consequence is that consumers begin to have an emotional response to the fact that their consumption is tied, however remotely, to the extreme violence of globalized production. Capitalism’s countermove? Commodify that response. The marketing strategies of SpaceX, Starbucks’, Tom’s and countless other businesses have been tweaked to tap the market created by our guilty conscience. Consider seals of approval vouching for far-off sustainably sourced worker-owned coffee plantations, the advertisement for a pair of shoes that goes to the nameless child in need for every pair you buy, the app that tells you exactly who was harmed and where in the making of that H&M hoodie. In each of these models the conscious-consumer is assuaged by a degree of control that they are given over the harm that they cause through their consumption. The ethical consumption craze is a pervasive marketing technique, ensuring that all kinds of goods and services must make some mention that their products are doing their part to chip away at a social problem. By tweaking the business model to incorporate and assuage consumer discomfort, globalized production processes transform the very act of purchasing into the promotion of social welfare.

Musk’s businesses are following suit. They insist that by being loyal to the brand one is by extension promoting the social good. “Buy a Tesla, save the environment.” But how true is it?

At a Tesla factory in Fremont, CA, one of the most expensive places to live in the Golden State, workers are paid between $17 and $21 hourly, well below the $30 national average for autoworkers. Estimates say that Musk’s companies are responsible for creating around 35,000 jobs altogether, and since many of these are classified as “green jobs,” his companies have garnered about $4.9 billion in government subsidies. But what’s green about a job where workers can’t afford to live near the factory and have to commute for hours in, you guessed it, regular fossil-fuel powered cars? Workers at Tesla have complained that language in their contract, ostensibly written to protect trade secrets, prevents them from unionizing for a fair wage. The same has been said of the contract at SolarCity, his solar energy company that is a subsidiary of Tesla. A unionized oil refinery worker can’t be expected to leave their six figure yearly salary in a “dirty job” to take up a non-unionized work installing solar panels. Some options present themselves: liquidate all the unions and let the market determine the wage across sectors, or unionize the so-called “green jobs”. One of those two futures seems decidedly more sustainable, but that is not the future that Musk and the state are interested in funding.

The same goes for Musk’s Hyperloop proposal, his plan for a honeycomb of underground tunnels that would connect large cities and solve the problem of lengthy, congested commutes. Again, far from eliminating the problem of congested cities caused by millions of cars, the Hyperloop would merely pack some of them into a high-speed tunnel. Musk maintains that his tunnels will be equitable, by which he means that they will be open to everyone. His claim begs some questions: Does everyone have a car in the future? Are all the cars electric? Can everyone’s car fit into this tunnel? As Paris Marx noted in Jacobin Magazine, the Boring Company (Musk’s corporation digging the tunnels for the Hyperloop) claims to be making quantum leaps into the future of underground transport, but projects in Madrid, Seoul and Stockholm have already achieved subway tunnel boring at costs similar to those that Musk once claimed only the Boring Company could achieve. Worse, the Hyperloop proposal can carry less than a third the passenger load of comparable high-speed rail projects: 3,650 as compared to 12,000 per hour. Musk believes that the Hyperloop is absolutely necessary, though, because it offers something that public transit projects do not: exclusivity and independence. Musk argues we need the Hyperloop because, “Don’t we all agree [that] public buses are disgusting”. The exclusivity of his ventures is betrayed in the language he uses to describe the public sphere and the fact the Boring Company’s first test tunnel connects Musk’s home to SpaceX headquarters in Hawthorne, CA. His commentary reinforces an opinion that the political right has spent years peddling, and has spent much energy on divestment to ensure its resonance. The opinion that spaces where people who don’t know one another interact, what we used to call public spaces, are necessarily grotesque and should, if possible, be avoided is the opinion that has eroded investment in public parks, libraries, schools and more. It’s also the opinion that Musk seems to hold. Better to own your own luxury electric car than to have to interact with a stranger on what could be affordable, reliable, and rapid public transit.

Viewed from this angle, the world that we’re allowing Musk to envision for us does not appear vastly different from the one we inhabit today—plagued with starkly segregated cities in terms of wealth and presumably still race, decrepit public transport and rising wage inequality— a future backed by billions of dollars of taxpayer funds.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention Elon’s romantic partner at the moment, synth-wave artist Grimes. She recently defended Musk against claims that he has supported union-busting surveillance and harassment tactics at Tesla. I’ve heard grumblings amongst old-guard Grimes fans not pleased with her decision to team up with Musk. Grimes is an artist who self-released her Dune-inspired concept album, Geidi Primes, in 2010. Her aesthetic painted pictures of worlds where freaks might be embraced instead of ostracized for their deviance, and some of us read into her music and her style a radical political stance that perhaps was never there. We have mistaken her deviant futurist aesthetic as implying that she held radical earthly politics. The reality is that we see what we want to see in public figures we admire, just as those of us who want to see Musk as a genius in jeans are willing to overlook more unsavory aspects of his work. And while Grimes never claimed that she was out to promote the social good with her music or her life choices, Musk certainly does. Their union then, is perhaps not so bizarre.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention Elon’s romantic partner at the moment, synth-wave artist Grimes. She recently defended Musk against claims that he has supported union-busting surveillance and harassment tactics at Tesla. I’ve heard grumblings amongst old-guard Grimes fans not pleased with her decision to team up with Musk. Grimes is an artist who self-released her Dune-inspired concept album, Geidi Primes, in 2010. Her aesthetic painted pictures of worlds where freaks might be embraced instead of ostracized for their deviance, and some of us read into her music and her style a radical political stance that perhaps was never there. We have mistaken her deviant futurist aesthetic as implying that she held radical earthly politics. The reality is that we see what we want to see in public figures we admire, just as those of us who want to see Musk as a genius in jeans are willing to overlook more unsavory aspects of his work. And while Grimes never claimed that she was out to promote the social good with her music or her life choices, Musk certainly does. Their union then, is perhaps not so bizarre.

The Boring Company just launched a new product, The (not) a Flamethrower. The “(not)” part was inserted as a media gimmick poking fun at the attempted regulations by the California legislature, which sought to place some limits on who could get access to this $600 fire-gun. In California where droughts and wildfires have been running rampant in the past year, and in an country where assault weapons are responsible for thousands of deaths per year, some regulation seems necessary. And yet the bill regulating the Flamethrowers died in committee, and 20,000 of them have been sold on preorder. Government regulation is no match for the appeal of an gadget that portends the kind of dystopia we’re headed for.

It may go without saying that in a nation confronted by catastrophic Trumpian policies on climate change, foreign affairs and domestic regulation, we should be keeping our eyes on the workings of the state. But we should not forget that as state regulatory apparatuses collapse and collude with private interests to undo any grounds for social cohesion, it is imperative to also be critical of Silicon Valley billionaires like Musk. It’s not AI we have to fear, as Musk implores us to believe, but rather the entirety of a hyper-capitalist world where innovations only exacerbate the difficult realities we already face. Changing the most disgusting realities of our current world will take more than one man’s vision.

It is admirable that Elon Musk counts mitigating the effects of global warming and moving us away from fossil fuel technologies as some of his primary goals alongside profit-making. But if we are willing to give him this much adulation, this much airtime, and this much public funding, we owe it to ourselves to hold him to higher standard because, despite what you may have heard, we are capable of designing abundant futures in which equity is not the handmaiden of profit, but the other way around.

What difficult realities? Never in human history has life been so good for so many. Unless you’re among those who romanticize the animalistic filth, slavery and misery of subsistence economies, or the planned-famine horrors of socialism.

Anyone trying to get -in- to Venezuela? No? Not surprised.

Who is this “we” you keep talking about, anyway? Between me and thee, there is no we.

PS: Musk’s “flamethrower” is a commercial roof-cleaner used for removing moss put in a futuristic-looking stock.

Dudette, you done got pranked.

I suggest surgical removal of the chill dill pickle.

Pingback: Unmasking Musk: Envisioning HyperCapitalist Futures – Increase Your Video Viewing Time Legally

Mr. Stirling,

Without even beginning to discuss the complex question of whether more people have attained “the good life” as a result of modernity, I would first refer you to the accounts of working conditions in Amazon factories across the US and Britain to highlight the evolving nature of low-wage work in ‘developed’ economies.

Jeff Bezos’ company receives government subsidies to provide labor to thousands of workers who then must still rely on government assistance to attain healthcare, and buy food despite being employed.

I doubt you think this is a good set of trade-offs for any government economy, capitalist, socialist or otherwise. If you do, I am interested in hearing your argument.

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/inside-an-amazon-warehouse-treating-human-beings-as-robots/

x

hillary

PS- I’m not certain what you’re referring to when you say ‘chill dill pickle’ but once again, I’m certainly curious to find out.