By Falih Hasan

In most nation-states in the Middle East, perhaps more so in Iraq, culture and literary activities cannot be understood separately from politics. In practice, the State makes use of culture and intellectuals to market its ideology and to legitimize its power. Many intellectuals associate with the State either out of ideological conviction or fear of official power, to be closer to decision-making, or simply for monetary reasons. Sometimes, they do so merely to survive. Iraq under the rule of the Ba’th Party (1968-2003) is a prime example of how culture and the intelligentsia fare under a totalitarian regime.

Once the Ba’th Party assumed power in 1968 following a coup d’état, it did not muster a great following among the intelligentsia, the majority of whom identified as leftists at the time. Gradually, however, whether through force or softer incentives, the Ba’th constructed intellectual cadres that identified (or pretended to identify) with its ideology. The regime ensured that everyone understood that there was no room in Iraq for any dissenting views. If one chose not to join the Ba’th party, then this person must still not be opposed to it. The Ba’thists worked hard to internalize this principle in the Iraqi people. In reality, this principle enabled them to start building their own literature and cultural practices, thereby rectifying their lack of any aesthetic theory. On orders from Saddam Hussein himself, Iraqi historians “rewrote” the history of Iraq to match with the Ba’thist view of the nation’s history. In 1978, Abdul-Ghani Abdul-Ghafoor, one of the few Ba’thist leaders who survived internal liquidation campaigns, explained that the Ba’th Party must impose its own internal educational traditions and cultural practices through official media, thus fulfilling Saddam Hussein’s orders to “transmit the traditions of the party to the State organs, and not to borrow State traditions into the Party.” Soon, there was no other voice but the Ba’th Party voice. The flight into exile of hundreds of leftist intellectuals in the late 1970s made it even easier for the Ba’th to dictate Iraqi culture and literature and further stifle any deviations.

The Ba’thification of Iraqi culture intensified during the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988), as “war literature” emerged as the dominant genre. The regime inaugurated an agenda of holding literary festivals and allocating prizes to poets, short story writers, novelists, and artists whose works “supported” the war efforts. In fact, artists, journalists, and literary producers were forced to spend a few weeks at the front to gain first-hand experience of the war and reflect their experiences in what might be called “Ba’thist Realism.” War literature also shifted literary production from an overabundance of poetry to an overabundance of fiction. In the 1980s, seventy-five novels and ninety short story collections were published, not including the huge number of short stories published in newspapers and literary magazines. More than four hundred stories were published in the first months of the war with Iran alone. The regime organized literary competitions and prizes, such as “Qaddissiyat Saddam Novels,” and “the Battle Divan.” However, a few other literary works, written away from the war fronts, stood out because of their vivid symbolism and veiled criticism of the regime. One wonders how they passed the censor. There were also literary magazines like Asfar (Writs), which appeared first in July 1985, Al- Taleaa Al Adabiya (Literary Vanguard), Al Mawqif Al Thaqafi (The Cultural Position), Al Aqlaam (The Pens), and Al Thaqafa Al Ajnabia (Foreign Culture).

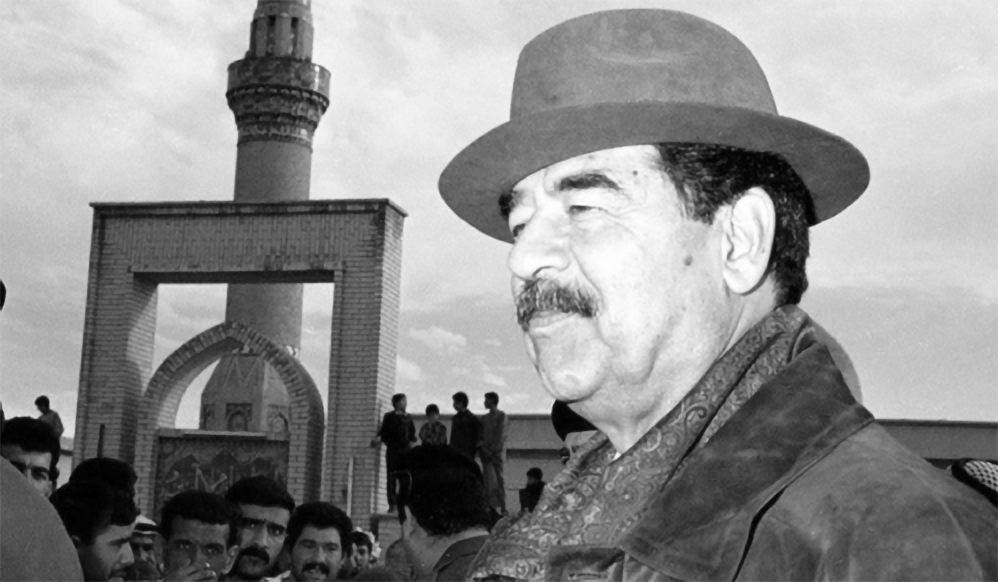

During the 1990s, following the Kuwait War, the regime organized a writing campaign. The Ministry of Culture and Information selected a number of novelists and asked them to interview a handpicked group of army officers and former war prisoners and render their stories into fiction. Saddam Hussein himself entered the fray, writing three mediocre novels and replacing the author’s name with “A Novel by its author.” In these novels Saddam glorified Iraq’s resistance to foreign invaders. No matter, his days were numbered.

After the overthrow of the B’aathist regime in March 2003, writers and literary producers suddenly found themselves in a free environment they were unfamiliar with. Under Saddam’s regime, cultural producers were accustomed to totalitarianism, which permeated all activities of social life – particularly its cultural aspects – and organized and shaped intellectuals’ activities. Literary meetings in cafés, discussion sessions, festivals and prizes, and publications were regulated by the regime. Some intellectuals now delude themselves into thinking that under the dictatorship they were more organized and productive than now, when censorship is gone. In April 2003, a line ended a history of dictatorship and a new era of expression and individualism was initiated in the country.

One day in late 2003 a list denouncing a group of writers was pinned to the columns of Al Mutanabi street, a symbol of Iraqi culture in central Baghdad, which forbade those writers from entering the street due to their service in the Ba’thist regime. A group of stall owners and booksellers in Al Mutanabi under the leadership of the bookseller Kareem Hanash prepared the list. Some exiled intellectuals who returned to Iraq after the fall of the regime supported the ban. The “blacklisted” intellectuals, however, responded with a serious warning: they would turn the issue into a tribal case to be resolved according to tribal mores. A colleague of mine decided to mediate between the two factions. The crisis was ultimately resolved by removing the lists from the street. This event had a major impact on Iraqi intellectuals: it could be viewed as a symbolic line separating two eras. It embodied two kinds of cultural performance: one within Saddam’s Iraq; the other in the diaspora. This episode is also indicative of the current political and the cultural reality. The event resurrected outmoded traditions, like tribal support – a resurrection that dates to Saddam’s attempt for tribal support of his regime and wars. It is, of course, telling that cultural figures would resort to tribal support, not to the state or to their writers’ union, to settle the crisis.

It is worth mentioning that Al-Mutanabi street was then targeted by several attacks, the largest of which was on March 5, 2007. The street, however, also underwent a “flourishing freedom,” unknown for more than 35 years. Sidewalk booksellers in this ancient cultural street now offer books in various fields: books on Islam and critiques of Islam; books critical of Saddam and the Ba’thist regime; and books critical of the invasion of Iraq and of the “colonial West.” However, the freedom of Al Mutanabi street does not see an equivalent on the pages of partisan newspapers. An independent press has not taken root in Iraq, and although the Internet has provided a free zone for writers and intellectuals, it has also opened the door to unethical journalism.

Another heated discussion emerged from the tensions between the intellectuals of the “Inside” and the intellectuals of the “Outside,” referring to those who remained in Iraq under the Ba’th and those who went into exile or simply left the country during the sanctions years. Writers of the Outside first raised the issue during the second wave of immigration of Iraqi intellectuals in the 1990s. After 2003, however, it was the writers of the Inside who revived it, saying that the writers of the Inside have been under a fierce regime while others have had it easy in the compassionate countries of the west and were indifferent to their colleagues at home. Even the writers of the Inside were internally divided for the same reasons. Many writers and authors throughout the Ba’th era were exposed to murder, torture and displacement. The writers of the Inside demanded that they play a greater role than the exiled and deserve to take their place in the new Iraq.

Once censorship was lifted with the collapse of the Ba’thist regime in 2003, about 254 journals appeared in Baghdad and dozens of satellite channels and radio stations were set up by mostly sectarian political parties. Some of these TV satellites and radio stations broadcast from abroad. The new media outlets needed writers and journalists. The intellectuals and cultural producers, primarily because they desperately needed a job, or perhaps for political and sectarian ambitions, again lost their independence as they rushed to work in these newspapers and satellite channels. These networks imposed new political, ideological, religious or ethnic constraints. Many intellectuals have been mired in these sectarian and ethnic swamps. The sudden change in politics and cultural production represented a shocking rupture with the past, which was characterized by censorship of ideas and expression, and punishment, imprisonment and displacement for these beliefs. But at present, however, Iraqi culture is chaotic, confused and troubled, and freedom is without limits or ethics. Independent intellectuals have found themselves to be the weakest group on partisan media platforms. Some were forced to leave Iraq because of their alleged links, however tenuous, with the former regime; for refusing political change; or for not agreeing with the new Iraqi administration.

The current era demonstrates that there is no independent intellectualism or independent cultural agents, a state of affairs which is not only modeled after but to a great extent due to the cultural policies of the Ba’th mandate of the “transfer of the party tradition into the State organs.” The self-proclaimed secular Ba’th party of the 1970s was suddenly transformed into “belief” and “Jihadology” in the religious campaign struggling against the “infidel western coalition” during the invasion of Kuwait and the sanctions years. In the 1990s religious aspects were promoted and seen in the streets of Iraq. The mixture of politics and religion became stronger, and had laid the foundations for the years after 2003.

After the toppling of the repressive regime, Islamic parties had a phenomenal resurgence. Shiite political parties claimed that they have the right to govern the country because of their decades in struggle against tyranny. In response, Sunnis asserted their “historical right” to rule Iraq. The two positions are based on sectarian grounds. The new Iraqi rulers are Shiite Islamic idealogues and their opponents are Sunni Islamic ideologues. The robust emergence of Kurdish nationalistic ambitions further complicated the situation because of what some consider an excessive insistence on Kurdish cultural and political autonomy. These trends cast their shadows on the intellectual and cultural scene. One might assume that the 2003 political earthquake would have made it easy for the leftist cultural trend to reassert itself. However, it seems that leftist intellectuals have abandoned this role, preferring instead to get involved with partisan dailies and political and sectarian polarization.

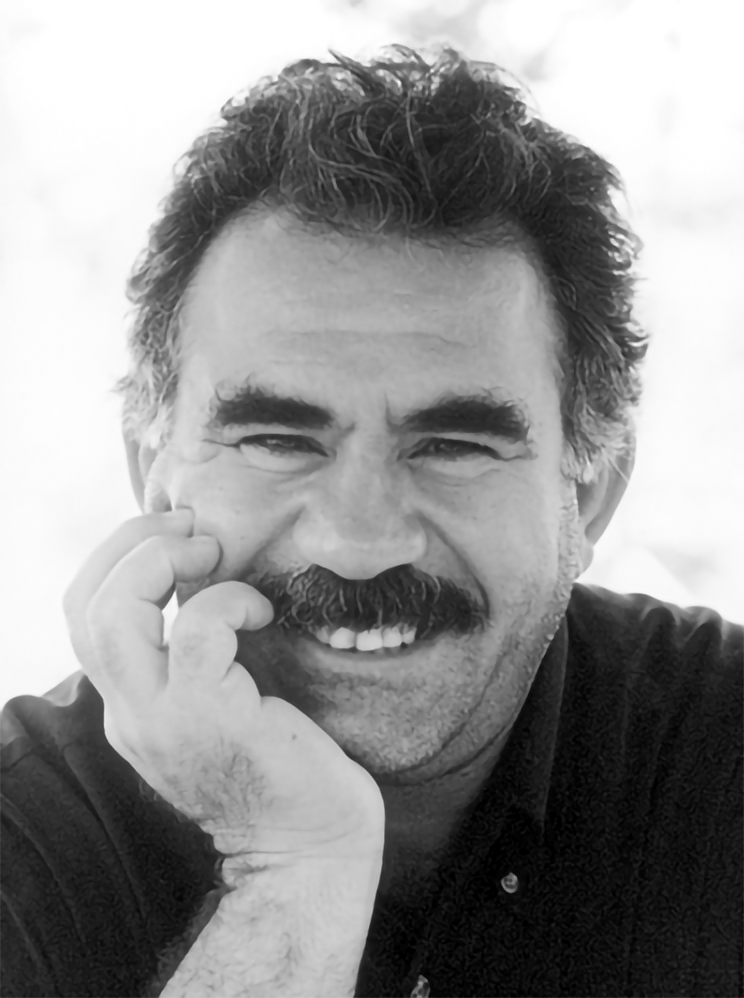

Iraqi culture has also been subject to regional intervention. Neighboring countries founded think tanks and study centers immediately after the fall of the regime, and funded news dailies and satellite channels. Even a clandestine political entity, like the Kurdish imprisoned leader Abdullah Ocalan of the PKK, provided some funding for a literary group in Baghdad in 2003 and 2004. Iraqi political parties used cultural centers in particular to achieve political ends. The Al- Sadr movement, for example, has the Cultural Center of “Ash Shahidayen As Sadrayen,” which sponsors book publication. A booklet written by a former bookseller and writer about his experience at Al Mutanabi street during the 1990s recently was distributed by the Center.

In Saddam’s Iraq, there were no private publishing houses. The only major publisher was the House of General Cultural Affairs of the Ministry of Culture and Information, which published books and magazines in several areas. In 2001, for example, the House published 199 books, 48 of which were on politics and partisan mobilization. From 2002 through March 2003, the total number was 156 books, 13 of which were on politics. The intellectual arena has yet to see the founding of “many publishing houses” as was expected after the fall of the regime. The House remains the largest publisher, though it has not had any remarkable growtht. In 2005, it published only 94 books, with five books in a series called “Culture of Democracy.” In 2008, 114 books were published. However, Iraqi publishing houses founded during the 1980s and 1990s in Germany and in Damascus, Al-Jamal (The Camel) and Al-Mada (The Large Horizon) respectively, relocated to Iraq and became the most prominent publishing houses in the country. It must be noted, however, that the practice of photocopying entire books, one which occurred during the years of sanctions, still persists. Lastly, many books on modern Iraqi history and political and social studies, written during the past decades, are being reprinted in Iran and Beirut, because of their lower production costs.

The climate of community self-expression, which became more present after March 2003, has encouraged Iraqi communities to assert their presence and define themselves in the so-called “new Iraq” while still defining their relationships with each other. But the transition from a dominant ethnic and sectarian, unilateral, and partisan ideology to a pluralistic, and multivocal one, has come at a high price, particularly in a turbulent regional environment swarming with sectarian and political conflicts.

The partisan spirit controls social life and practices. In 2003, many cinemas were closed throughout Iraq, including Kurdistan. The violence that followed the fall of the Ba’thist regime forced the cinemas to close. More recently, improved security and the diminished influence of religious political parties have given impetus to reopen the theatres. There are now three cinemas (there were about 20 in the 1980s) in Baghdad. The security situation, the spread of Islamic extremism, government indifference, and satellite channels are the main causes of diminishing cinema and theater activities. In September 2010, it was reported that the Babil Provincial Council decided to prevent singing and dancing troupes from participating in the Festival of Babylon. Due to this heavy-handed intervention, this cultural Festival has been declared by many writers and journalists as a failure. This episode demonstrates the influence of Islamic parties on certain official cultural events and activities. There remains an irreconcilable contradiction between many public trends and many Iraqi political parties. Most radio stations (there are now more than 150 radio stations in Iraq) broadcast songs and entertainment programs. More telling is the fact that the Iraqi street has seen a remarkable return of non-religious activities, as seen in the proliferation of nightclubs and other entertainment establishments. The parliamentary elections of March 7, 2010 showed that religious sensibilities were not be as important to the population as basic services and living standards.

The violence that followed the fall of the Ba’thist regime forced the cinemas to close. More recently, improved security and the diminished influence of religious political parties have given impetus to reopen the theatres. There are now three cinemas (there were about 20 in the 1980s) in Baghdad. The security situation, the spread of Islamic extremism, government indifference, and satellite channels are the main causes of diminishing cinema and theater activities. In September 2010, it was reported that the Babil Provincial Council decided to prevent singing and dancing troupes from participating in the Festival of Babylon. Due to this heavy-handed intervention, this cultural Festival has been declared by many writers and journalists as a failure. This episode demonstrates the influence of Islamic parties on certain official cultural events and activities. There remains an irreconcilable contradiction between many public trends and many Iraqi political parties. Most radio stations (there are now more than 150 radio stations in Iraq) broadcast songs and entertainment programs. More telling is the fact that the Iraqi street has seen a remarkable return of non-religious activities, as seen in the proliferation of nightclubs and other entertainment establishments. The parliamentary elections of March 7, 2010 showed that religious sensibilities were not be as important to the population as basic services and living standards.

Religious political parties are now experiencing a decline due to their failures, and are scrambling to retain their claimed community basis. In Kurdistan, which has fared better than the rest of Iraq, freedom of expression and opposition to the two leading blocs are unwelcome. It has been reported that a number of journalists have been killed for criticizing influential leaders. The structure of tribalism, religious sensibilities, and corruption in the administration still restrict everyday life in Erbil, the capital of Kurdistan. Sulaymaniyah proves relatively more tolerant: a leading cultural institution, Sardam seeks to bridge the gap through an Arabic version to the dominant culture in other areas of Iraq. Opposition newspapers both in Arbil and Sulaymaniyah suffer from constrictions. The newspaper Hawlati, for example, has no sufficient financial support to publish regularly in Erbil, and when it appears, the authorities withdraw it from stalls and bookstores. The relative security and prosperity of the Kurdistan region led Al-Mada to organize cultural festivals in Erbil.

The poor performance of political and governmental personalities and a desire to play a leading political role encouraged writers to seek a more active role in politics. Many authors and writers nowadays appear on TV as “political commentators,” “analysts,” “political columnists,” or simply as ‘thinkers,” while abandoning their independent projects and literary activities.

Public places and squares were filled, especially in Baghdad, with statues of the former dictator and his party’s most symbolic monuments. Once the regime fell, its opponents rushed to destroy the statues and monuments associated with it. At the peak of extremist group activity, the statue of the Abbasid Ruler and founder of Baghdad Abu Jafar al-Mansur in the Karkh side of Baghdad was blown up.

A few years later, a committee to stamp out the culture of the old regime was established in coordination with the Baghdad mayoralty. This was mostly in line with the de-Ba’thification campaign. Most artists had no objections to dismantling the cult of personality. A famous Iraqi artist and sculptor, Nidaa Kadhim, although supportive of dismantling these dictator-related cultural artifacts, made a few observations. He criticized the lack of awareness among authorities, who continued to erect new statues and monuments on the same basis. Kadhim believed that this practice would ensure that the place would always be associated with the original statue and thus the base of the new statue would recall the old statue. He called for the redistribution of statues and monuments according to a new artistic geography. Nidaa Kadhim is responsible for creating a statue of the poet Al- Jawahiri. The sculptor paid attention to the link between the Iraqi intellectual and politics. He explained that since the 1940s until his death in 1997, Al-Jawahiri had experienced several political changes. Consequently, said Kadhim, “I must do more than one statue and put them in several places in Baghdad to fully describe the political transformations of the poet.”

Traditional Baghdadi literary salons, or Al Majaliss Al Adabiah Al Baghdadiyah, where various topics are discussed, have resumed their activities. In July 2010, writers published the first quarterly magazine titled “Al Majaliss Al Adabiah.” Some politicians, like the former parliamentary representatives Safiyah Al-Suhail and Wael Abdul-Latif and Iyad Jamal Eddin, formed their own literary forums. It appears that politicians wish to be in contact with both intellectuals and the general public. Perhaps it is unsurprising that the number of literary salons has reached twenty.

Al Mutanabi Street could be described as the pinnacle of freedom and intellectual tolerance in Iraq, a place where you can find books and journals of varied trends and opposing viewpoints, displayed side by side in the street stalls or on bookstore shelves. Unlike Al-Mutanabi Street, the newspapers and satellite channels do not show tolerance. They are either for or against. Thus, media outlets have become a platform for ideologies and specific political positions, rather than a means to transmit news and facts. In Al-Mutanabi, stall owners and booksellers sought to reprint books on contemporary Iraqi history, even Arab-Islamic history books, in response to popular demand. It seems that this phenomenon is caused by the search for identity for the country among different ethnic groups, religions and doctrines. The history of Iraq’s Jews and Christians, for example, is being reexamined and rediscovered.

Worth mentioning, too, is the fact that new words and expressions entered the Iraqi lexicon, including terms such as “majority, minority, freedom of expression, election, vote, political bloc, parliament, representative, right of difference, government (or rule) term, media freedom, secularism, the separation of powers, federation, etc.” Many writings now deal with modern social issues, such as civil society and non-governmental organizations, in addition to examining Iraqi social and political problems. The origins of the sectarian question and the challenges of coexistence among communities are often discussed. Questions about the rise of Islamism and Islamic rule are also raised on TV shows and in journal articles.

Amidst this state of affairs, many intellectuals have taken the initiative to encourage the government to sponsor their role in Iraq’s political rebuilding and to grant them a special place as the elite. The Intellectual and the Politician are now a popular topic. Some intellectuals even called for introducing an article in the Iraqi Constitution recognizing the role of the intellectuals and their high importance. Others presented a draft law to the House of Representatives that would give them a role in the new Iraqi state. A number of intellectuals called for the formation of their own political party. This illustrates their tendency for and desire to partisan political activities. It appears that intellectuals want the government to sponsor them and organize their activities and cultural events instead of becoming independent agents building projects on their own without the state or religious and political parties. Unfortunately, in the present era of chaos and unrestricted “freedom,” intellectuals are largely neglected and ignored. For example, the Iraqi Ministry of Culture is the sole ministry that no major political party wants to assume because of its triviality. One person who took over the ministry portfolio is an accused murderer, now a fugitive from justice.

The Union of Iraqi Writers itself – like its counterparts in other Arab countries –became a field of struggle for cultural hegemony since its foundation on July 7, 1959 until the late 1970s, when the Ba’th drove leftist intellectuals into exile, prison, or oblivion. The Union’s legitimacy was questioned in the early 1960s because of the conflict between pan-Arabist writers, both inside and outside Iraq, and leftists or Marxists inside Iraq. History seems to be repeating itself after the radical changes in Iraq in 2003. This time the Federation of Arab Writers, based in Damascus, questioned the legitimacy of the Union of Iraqi Writers, accusing its members of being “traitors dealing with the occupiers.” Consequently, Iraqi membership was suspended. The Federation of Arab Writers, in its 2009 session in Sarat, Libya, demanded that Union of Iraqi Writers “declare its position in support of the Iraqi resistance against occupation” as a condition to end suspension. Some anti-change writers – many of whom were part of the Ba’th propaganda machine –founded an association called the Coalition of Iraqi Writers and Literary Figures abroad as an alternative to the Union at home. Other struggles are waged within the Union of Iraqi Writers among members allegedly sponsored by the ICP and those from other ideological persuasions. This is another indication that the literary and cultural arenas in Iraq remain heavily influenced by politics. It appears that Iraq may be heading into the protracted process of building a national identity since it has not yet constructed a “Grand Narrative” to articulate the nation-state. The post-invasion era has entailed the rise of the ethnic and sectarian intellectual and the diminished presence and role of the independent intellectual in the cultural arena and the public sphere. The complexity of the political process and sectarian and ethnical tensions may drive writers to re-examine their history to find answers to questions of identity, their public role, and their function in Iraqi society.

Pingback: Une bibliographie complémentaire pour préparer l’agrégation d’arabe (session 2021) – Le Carreau de la BULAC