Adi Sieradzki

Post-surgical bras are not products often thought about by the general public. Their very specific market is targeted at a very specific audience: women who have undergone a mammoplasty removal procedure, either a lumpectomy (partial removal of breast tissue), a unilateral mastectomy (when one breast is surgically removed), or a double mastectomy (when both breasts are removed). For women who have had any of those surgeries, acquiring a post-surgical bra not only means rehabilitation, but also a normalization of their bodies. Comfort is not a consideration in the design of these products. Rather, women opt to wear post-surgical bras because they wore bras before their surgery/ies and are accustomed to seeing a certain breast shape both over and under their clothes. Sometimes, these bras are only used during the median stage prior to breast reconstruction. But sometimes, they are a new and permanent reality, symbolically and literally: they complete what is now missing. How do post-surgical bras connect fashion and medical treatment? How do social norms of gender apply to their design?

Post-Surgical Bras as a Concept and as a Reality

Like much of what we consider “disposable” fashion, lingerie that relies on perpetual obsolescence and therefore on constant regeneration. Within the lingerie market, however, bra sales hinge on several contingencies: price, fit, and use value. Although bra materials are more durable than those of underwear, they are still prone to lose their elasticity and thus their basic function. After all, if a bra can’t hold up its contents, it’s not a good bra. Despite ongoing discussions on how a bra should fit and function, the mass market nonetheless standardizes size by band and cup, as well as shape and style.

Post-surgical bras are either a step during rehabilitation for the wearer, or provide ongoing support to the wearer for the rest of her life. This is true for post-mastectomy patients opting to wear a prosthetic insert in their bras. The medical benefits of post-surgical bras lie not only in wound compression (provided the bra is the correct choice for the patient), but also offer drain support prevention of dermatological side effects. For breast cancer patients who opt for breast reconstruction, the post-surgical bra shapes the new breast in such a way that it expedites the healing process. This, however, is their ideal function.

In reality, the post-surgical bra market is more complicated and often causes regression, rather than progression, of healing. As Samantha Crompvoets (2012) found in her research on bras with prosthetic inserts, their benefits are far from what advertisements or doctors claim: women who use them describe a life of discomfort and fears of wardrobe malfunctions and unforeseen maintenance problems. Many problems are due to the prosthetic inserts themselves, rather than the bras. This may also be true for other types of post-surgical bras. That being said, post-surgical bras with prosthetic inserts are still considered the better option than a post-surgical chest binder (Laura et al.), which looks like a constrictive sports bra and is intended to apply intense wound compression.

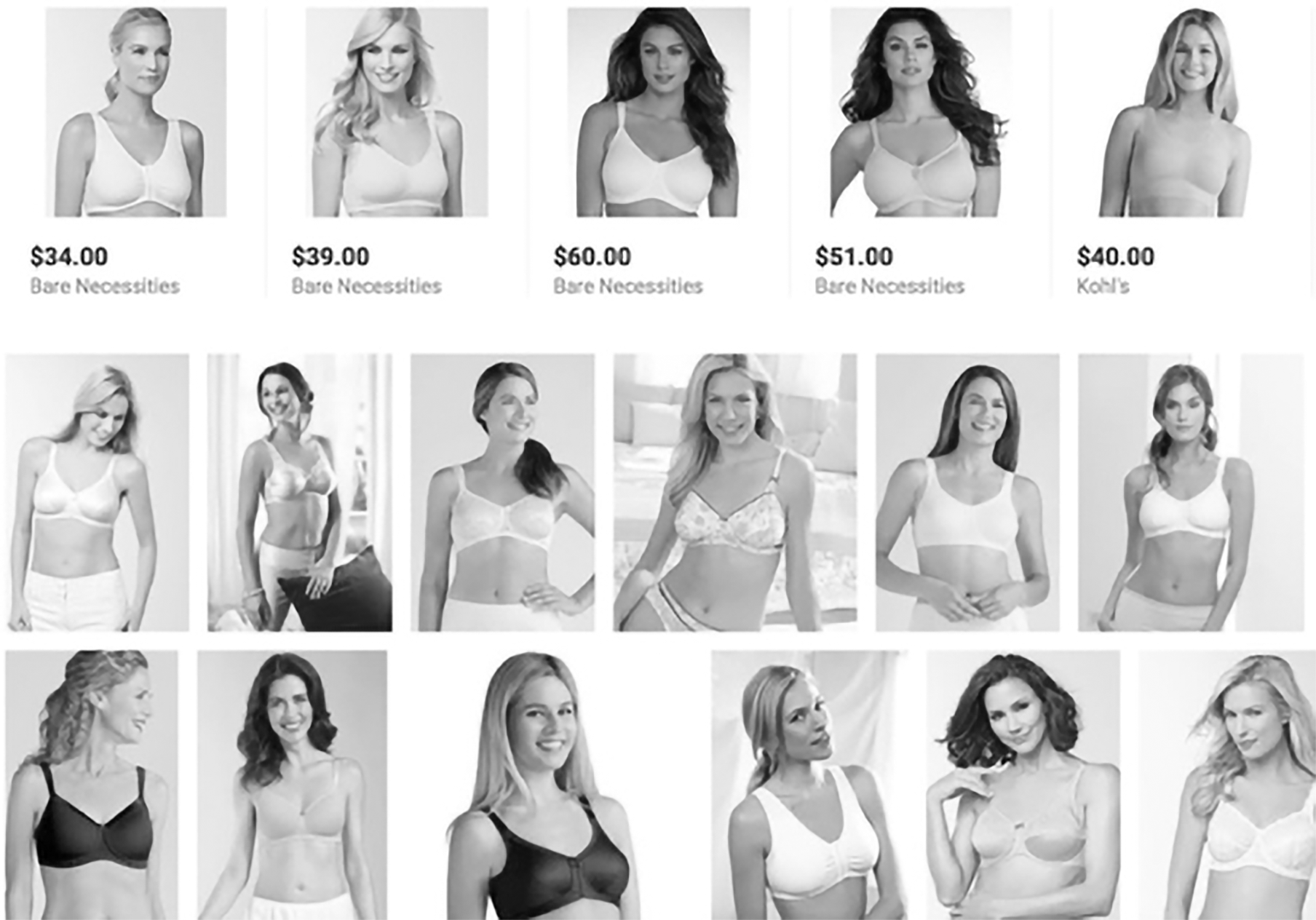

The choice between wearing a bra with a prosthetic insert or a medical chest binder introduces problems of aesthetics, comfort, and affordability for women. Neither is an ideal choice: post-surgical bras with prosthetic inserts are uncomfortable to wear and potentially embarrassing when the prosthetic insert moves out of place (Crompvoets). These bras can help women conform to their pre-surgery aesthetic routine, but often come at the price of marked discomfort and a high financial cost. Amoena bras with prosthetic inserts, for instance, start at $30 for the bra alone, and the prosthetic insert can cost anywhere between $100-$300 (Fig. 1). Then there’s the issue of online purchasing, which is ubiquitous enough to merit a closer look at the bras available.

A cursory search of specialist online retailers such as The Mastectomy Shop shows that their inventory does not consider cases of women who cannot lift their arms post-surgery (they only offer chest binders with straps), women with very large breasts (above cup size F and/or band size 38), or women with a limited budget ($35-$100 per item). Amazon.com is another popular retailer for post-surgical bras. Although their prices may be lower on average by between $30-$90 per item, size and style options are limited (Fig. 2). Additionally, any woman recovering from mammoplasty needs at least one type of “recovery item,” as she would likely need to launder the bra frequently and wash the prosthetic insert to prevent skin infections around the surgical scar. This would at least double the financial cost for many women who must purchase two of each bra or even a second prosthetic insert. Given the uneven nature of health insurance coverage for post-surgical bras in the United States, this is a highly troubling issue. Women can potentially face thousands of dollars in expenses in purchasing post-surgical bras just for temporary use.

Looking at the examples given above for post-surgical bras, it’s hard not to notice two things: the whiteness of most bras, and the whiteness of the bra models. The variety of post-surgical bras in hues of white and beige seem entirely counter-intuitive, as many women experience different kinds of leakage around the surgical area. A white bra would make the presence of fluids much more visible than a darker bra and the stains would be harder to remove, especially if the bra is made from delicate fabric. The white hues also mimic the color of the pictured wearers, who are also nearly all white. The proliferation of white mastectomy bra models demonstrates the market’s bias against women of color, despite the fact these women are, often likelier to be diagnosed than white or Asian women (DeSantis et al.).

Post-Surgical Bras in Gender Theory

The question of the aesthetics of post-surgical bras is important because these are products that, ideally, provide physical and mental aid to their wearers. It intersects with the feminine bodily experience within a patriarchal society and the with the internal misogyny the bra market promotes. What happens when the “whole” feminine body is disrupted, particularly the breasts? Samantha Crompvoets (2012) discusses the social inscriptions upon femininity of the healthy body with two breasts and the affective consequences these norms have on breast cancer patients. Though her research focuses on the market’s use of bodily inscription on breast protheses, she also notes that post-surgical bras are part of the healing process: bras, which are part of the “normal” female experience, thus carry a return to the everyday routine. This normalizing process ties into the broader cultural and social construction of “pink ribbon culture.”

In her book Pink Ribbon Blues, Gayle Sulik tackles pink ribbon culture, or the mainstream American cultural phenomenon of women diagnosed with breast cancer. As a disease that mostly attacks women (90% of the patients), breast cancer was promoted to the public agenda in the 1970s and has only become more visible since. As a disease that attacks women in one of their most vulnerable areas, areas that are culturally and socially tied to public conceptions of a woman’s “worth”. In the eyes of Western society, a woman with a diseased or mutilated breast is lesser. The concept so pervasive in the aesthetic ideals embedded in mainstream media, that even women without breast cancer will modify their breasts to meet social standards of beauty and worth.

In her discussion of pink ribbon culture, Sulik echoes sentiments most famously described by Barbra Ehrenreich in her Harper’s Magazine essay, “Welcome to Cancerland.” Both Ehrenreich and Sulik consider this culture both insular and corporate. Breast cancer is the most profitable type of cancer for health service providers, thus attractive to health insurance providers. As a highly publicized yet private disease, it attacks women in huge numbers (“everyone knows someone”), but it also attacks women individually at the most culturally-contingent, vulnerable level. Society cheers afflicted women on their “fight” against cancer yet shames them for their non-normative gender performances post-surgery.

Post-Surgical Bras Within Broader Critical Theory

To understand what it means to have a diseased breast and why so many women seek to hide them from the public using prosthetic inserts and special mastectomy bras, I turn to Judith Butler and Michel Foucault for explication. Judith Butler, in her works on gender performativity (1990) and embodiment (1994), deconstructs what society conceives as gender and the body. Both, she theorizes, are not natural concepts and have never been. Instead, they are constructs created by public institutions for the sake of governance. Society performs gender to fit in, to fulfill the criteria of what is an ideal body is. Those who challenge these norms, whether by denying the gender binary or heteronormative sexuality, by being a person of color, or by not being able-bodied, are ostracized and eventually punished. Butler is concerned with the materiality of human existence because human bodies are governed material.

Gender performativity (or, as Butler later called it, citationality), is the concept of human behavior that reproduces social constructs of gender. When women feel that they must present themselves as feminine, they reproduce femaleness as a gender. Tied to femaleness are notions of a certain kind of attractiveness and softness that appeal to heterosexual men, who in turn are educated to desire only that kind of femaleness. Because this is the most common form of female performativity in Western society, it’s no wonder that women feel compelled to perform it at all times. This kind of performance is related to the psychological comfort breast cancer patients feel when they opt for different types of reconstructive surgery beyond the procedure intended to save their lives. This phenomenon is even more sinister.

Breast cancer-related surgeries can often result in a pair of misshapen breasts, or instances in which one breast has been removed, creating the need for either reconstruction or prosthetic inserts. Magdalena Wieczorkowska (2012) explains breast cancer surgical procedures and their consequences as a phenomenon related to Michel Foucault’s theories of bio-power: by raising national awareness for breast cancer as a leading, preventable cause of death for women, political and medical institutions categorize it as a danger to society. As a result, combative surgical procedures fall under what Wieczorkowska calls “ultimate governmental power,” unlike plastic surgery procedures (which are considered more to be symptoms of aesthetic social conditioning). By this, she means that lumpectomies and mastectomies are government-endorsed procedures which alter the female patient’s body with the intention to cure her cancer and transform her back into a healthy, productive citizen.

Wieczorkowska also points out that the lack of recognition for breast cancer patients’ physical needs directly clashes with Western notions of socio-aesthetic ideals. In other words, female breast cancer patients first experience the medicalization of their breasts through institutional power (which robs them of their conditioned self-image). They are then made to conform to socio-aesthetic ideals after undergoing debilitating and deforming medical procedures by either hiding the results or seeking plastic surgery. Any additional surgery on the area could further damage their self-image and bodies. There are also racial disparities between women who undergo breast reconstructive surgery in either form, with Black women represented in significantly lower numbers than white, Asian, or Latina women.

The invention of the post-surgical bra, therefore, reconciles these tensions. With it, patients will attempt to reconcile the medicalized and fragmented female body, the commercial-aesthetic concept of the fragmented female body, and above all, the unification of the fragmented body parts into a whole. Women exist as both fragmented and whole-bodied in current society as aesthetic expectations tend to fragment their bodies into parts in need of “improvement” (i.e. de-aging processes or emulating an idealized view of the body part). With post-surgical bras, they re-assimilate their breasts, once condemned as diseased by medical professionals, into social expectations.

The Post-Surgical Bra and Bandage Market for Breast Cancer Patients

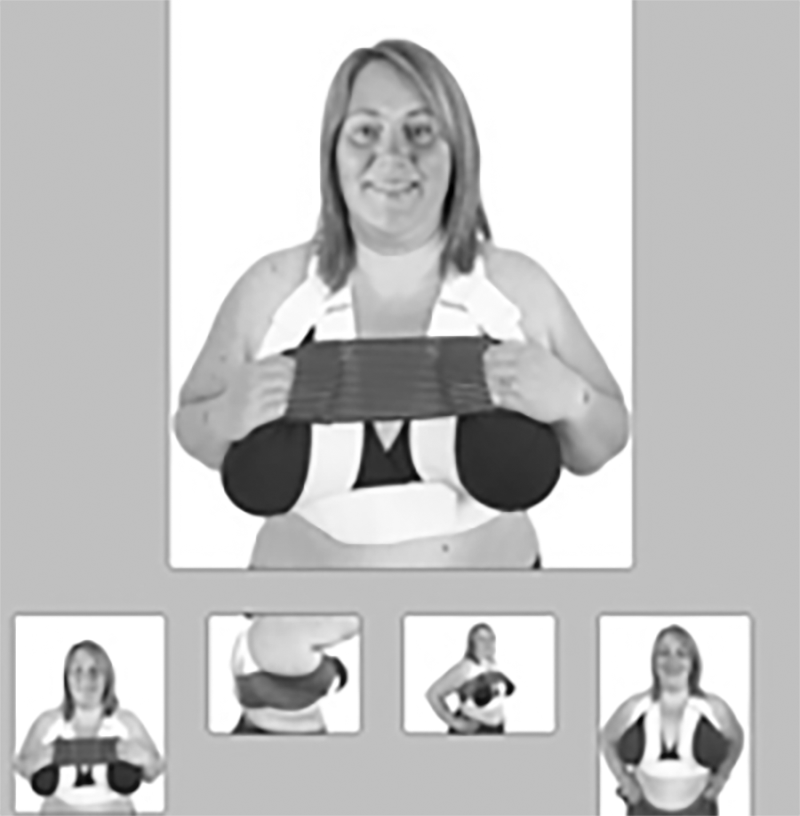

Though post-surgical bras are common to all versions of mammoplasty, they are especially so for lumpectomies (or “breast-conservation surgeries”) and unilateral mastectomies (full removal of one of the breasts), as they are procedures in which the medical consideration supercedes aesthetics. The SilversteinWrap is an example of a medical post-mastectomy bandage (Fig. 3), the QualiBra is an example of a post-surgical bra (Fig. 4), and the Amoena bra is an example of a bra with a prosthetic insert (Fig. 5). The SilversteinWrap allows for a variety of bandaging techniques, but is very thick and therefore visible under clothes. The QualiBra allows for breast support with different options for larger breasted women (to “preserve dignity,” as its marketing asserts), but as one can see, it is very unflattering and aesthetically unappealing. The Amoena bra is the most aesthetically pleasing of the three, but is not intended as a specifically post-operative support, but rather to support a longer healing stage or in post-treatment life. It is included here to show that aesthetics can be considered for female patients.

The post-surgical bra was invented due to the lack of attention to the needs of post-operative female patients by an overwhelmingly male medical profession charged with their health and recovery. To this day, there are no options for post-surgical bandages which also function as bras, despite a clear need for them. Women are expected to undergo mammoplasty procedures, some of which are live-saving, and walk around afterwards with both a bandage and a bra. These experiences could hinder their psychological healing process. By failing to provide an option which correctly accounts for the non-normative shape of the post-operative female body, the medical industry demonstrates its indifference to the physical and psychological implications that invasive procedures can have on the mental state of female patients.

The concept of the female patient is also closely tied to the concept of the female consumer, provided those consumables relate to non-medicalized, gendered products. In this specific case, non-medicalized, gendered products would be lingerie. With lingerie, the female consumer has the power to choose even if the range of choice is not ideal. Once the invisible medical border is crossed, the choosing rehabilitative products is the responsibility of the surgeon or oncologist. Women may purchase post-surgical bras as long as they fit with the bandage the surgeon has placed on them once the surgery itself is done. Those bras are not covered by health insurance, for most part. There are some, but few, cases in which patients are marginally remunerated for expenses.

In a June 2017 conversation with Yael Gibor, an industrial designer of post-surgical bras and a woman at risk for breast cancer, we discussed the difference between what the medical market offers and what it could offer to breast cancer patients. This kind of consumption is not often considered by women as consumers until they are diagnosed with cancerous tumors. Gibor described multiple conversations she has had with breast cancer patients undergoing treatment who experienced allergic reactions to surgical glue and bandage material, the inadequate positioning of the breast drains, and poorly-fitted compression of the wounds. Her own personal experiences of breast biopsies taught her that those reactions are not limited to post-surgical stages: they could be experienced by any woman with a breast cancer scare.

Gibor heavily criticized the medical and public markets for being rife with products that fail to provide satisfactory service to their customers. Maybe, if medical product companies considered doing customer surveys with patients using their products, some change could have been brought. Right now, Gibor believes, finding the solution is left to the patient. Consequently, an unregulated commercial field is wide open for all kinds of products in a range of prices, many of which do not offer the correct breast support and wound compression to the user. In a May 2017 email exchange with a breast cancer patient who has undergone four surgical procedures, including reconstructive procedures, the following issue was also raised: doctors themselves are not always sure what level of wound compression is required in mammoplasty or breast-related procedures. This kind of medical guesswork leads to a lot of errors for female patients, which ultimately lowers their quality of life and impedes their healing. This is a medical travesty and it seems unlikely to change in the near future.

Concluding Thoughts and Recommendations for the Post-Surgical Bra Market

To consider the lives of women who live with breast cancer and its ramifications on their bodies is the enactment of three simultaneous, discrete conversations: one, of academia decrying the objectification and dehumanization of women; the second, the loudest voices in the fashion and medical markets, unaware of this critique; and third, the voices of the women as consumers and women as patients. To observe the lives of women who live with breast cancer is to see them coping with a myriad of complications, performances, and trauma. Their lives are further challenged by banal representations of women living with breast cancer in movies, tv shows, advertisements, and blogs.

The healthy female body, as the media reminds us daily, already comes with a set of unreasonable expectations for women to strive for. The ill female body, therefore, must fulfill socially constructed criteria first of what it should be, and then recover even further, back into the state of the “healthy” female body. This would mean the appearance of a woman who has “survived” and “beat” breast cancer. Women must be “strong warriors” who “fight” an adversary lodged in their own bodies, and they must relish the fight. This is exactly the type of discourse Barbara Ehrenreich railed against in Harper’s Magazine, because it stops women from voicing their fears and anxieties and mutes the voices of those who are, in fact, dying of breast cancer.

Given the current state of breast cancer as a social phenomenon, a market, and a culture, any orientation towards the needs of the actual patients is unlikely. Western medicine has repeatedly shown it centers around white, cisgender, heterosexual, able-bodied males. When women are diagnosed with breast cancer, the majority of physicians in charge of their treatment are male (AMA Wire). Those male doctors, whether oncologists or surgeons, cannot fully understand what it means to have breast cancer. They are only aware of how it can be treated medically and what medical complications it may entail. The long-term comfort of breast cancer patients is adequately addressed within the medical community. Treatments for breast cancer, like any cancer, can be extremely damaging to the body even without aesthetic considerations in mind. How can these shortcomings be ameliorated?

First, the invention of a post-surgical bandage that could function as a bra would have a tremendous impact. While there are prototypes of such a product in development, it’s uncertain whether they’ll ever make it to mass production and full market presence. Because post-surgical bandages of all kinds have to be medical-grade bandages with full FDA approval, perhaps an established surgical bandage company could develop this product or purchase a patented design. With enough investment behind the product, it may prove to be profitable. It would not necessarily compete with mastectomy bra companies (such as Amoena), because all surgical bandages are one-time use. Integrating such a product into the sustainable fashion industry is more complicated and requires considering the other available options.

Second, a campaign for better representation within the post-surgical bra market. This not only has to do with diversity of the models’ race, but also with cup size and color diversity. Even within current market offerings, with all the issues they entail, post-surgical bras could be better marketed to their diverse customer base. For instance, if post-surgical bra companies like Amoena and Marena offer bras in colors that mimic skin color, diverse representations if race could be offered by diversifying the color range. Companies could offer post-surgical bras in cup sizes larger than D or E, especially as the bra fit conversation is shifting towards bigger cup sizes over the standardized range. It is important to offer these options because the women who can’t access them are more likely to experience adverse physical and psychological side-effects during their recovery and rehabilitation stages.

Lastly, a better relationship among doctors and patients must be nurtured. Women as patients react differently to doctors of different genders, and so do men. This has negative implications for patients with breast cancer, where gender differences might prevent patients from voicing their needs or having them heard. A male surgeon or oncologist who already compartmentalizes his medical experiences and prefers to stay emotionally distant may not fully understand how damaging breast cancer is on his patients’ psyches, even when they are in remission. A network in which patients feel comfortable relaying their everyday side-effects and developments – perhaps communicated either through an online platform or by a liaison to their doctors – would be a positive change. While similar networks are already in place, this proposal considers the myriad issues of pink ribbon culture its harmful implications. By talking to someone in a casual setting regularly, perhaps patients would be able to express their fears and concerns without being stifled by “objective” and scientific expertise. Although many patients probably explore therapy options, offering another (free) venue for would be very helpful.

Some of these suggestions may seem related only tangentially to the topic of post-surgical bras, but all of this is symptomatic of a far larger issue: the censorship of women’s voices. Breast cancer is considered a disability under United States federal law, but because of social phenomena like pink ribbon culture, the weight of this recognition has been diminished. Instead of acknowledging that going through surgeries and treatments, losing work and endangering relationships, and yes, even spending a lot of money on special clothess, pink ribbon culture trivializes these personal experiences. Female breast cancer patients deserve to be treated with understanding and respect born of recognition for what life with breast cancer really is like without the lens of social and cultural norms.

Works Cited:

Butler, Judith. Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity (Thinking gender). New York: Routledge, 1990.

Butler, Judith. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “sex”. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, 1993.

Crompvoets, Samantha. “Prosthetic fantasies: Loss, recovery, and the marketing of wholeness after breast cancer.” Social Semiotics, vol. 22 no. 1, 2012, pp. 107-120. doi:10.1080/10350330.2012.640058

DeSantis, Carol E. et al. “Breast cancer statistics, 2017, racial disparity in mortality by state.” CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.3322/caac.21412. Accessed 22 May 2018.

“Different Databases, Differing Statistics on Racial Disparities in Immediate Breast Reconstruction after Mastectomy.” American Society of Plastic Surgeons, 29 March 2017. http://www.plasticsurgery.org/news/press-releases/different-databases-differing-statistics-on-racial-disparities-in-immediate-breast-reconstruction-after-mastectomy

Ehrenreich, Barbara. “Welcome to Cancerland. (criticism of ‘cult of the survivor’ which has grown up around breast cancer; fear that disease is being presented as a positive even normal experience and its causes ignored). Harper’s Magazine, vol. 303 no. 1818, 2001, pp. 43-53.

Laura, Sharon et al. “Patient preference for bra or binder after breast surgery.” ANZ Journal of Surgery, vol. 74 no. 6, 2004, pp. 463-464.

“Retail sales value of the sports bra market worldwide from 2009 to 2019.” Statista.com. http://www.statista.com/statistics/480919/global-sports-bra-market-retail-sales-value/. Accessed December 10, 2017.

Sulik, Gayle. Pink ribbon blues: How breast cancer culture undermines women’s health. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

The Mastectomy Shop (2018). Mastectomy bras. https://www.mastectomyshop.com/categories/Bras/

Vassar, Lyndra. “How medical specialties vary by gender.” AMA Wire, https://wire.ama-assn.org/education/how-medical-specialties-vary-gender. Accessed 22 May 2018.

Wieczorkowska, Magdalena. “Medicalization of a woman’s body – the case of breasts.” Przegląd Socjologiczny, vol. 61 no. 4, 2012, pp. 143-172.

Aside from a few brief mentions of the gender binary, this article is woefully lacking in attention to a significant portion of consumers for post-surgical bras: trans people. The article also elides trans experience by consistently referring to people using these bras as “women,” thus negating all the theoretical engagement with binary critique. How can an article about post-surgical bras and the performance of gender ignore and elide trans and non-binary people so completely?