Inmaculada Zanoguera Garcias

In the name of Allah, the Gracious, the Merciful.

After 2020 uprooted the foundations of our collective and individual worlds, 2021 took the reins with both further devastation, and a slight sense that a better world may just be on the other side of the horizon, somewhere. For too many, the trivial temporal jump from the previous year to the present one has been exactly that—trivial, meaningless—bringing no new beginning, failing to improve a local and global landscape marked with structural inequalities whose effects are being felt at ever increasing rates. As an offset of the pandemic, still in this new year, new budget cuts, rising unemployment, and the gruesome violence of many discriminating public health systems in the West—exceptionally in the United States—do little to ameliorate the state of social crisis whose impacts, as we well know, cause uneven harm on Black, Brown, and poor communities.

Moreover, as we bear witness to impactful, if not entirely shocking, public displays of white supremacy in the United States, and the level of impunity with which they are met, the disturbing truth is that we do not know if the worst is already behind us. Yet, it is precisely while traversing the uncertain terrains of political, social, and spiritual crises that imagining utopic alternatives—imagining reconstructions—becomes so crucial a task, both before and as we plan and fight for them. Because the social justice struggle—used here in the general sense to refer to Liberation, Decolonization, Abolition, and so on—so infrequently yields tangible results with which to quantify progress, it becomes equally important to articulate and share our sources of hope. To remind one another, put simply, that we are not alone. Rather, we work and struggle with the compresence of thousands of movements, comrades, sisters, and brothers that exist in this and past times.

I remind myself of this as I seek to honor the human need for hope. Hope that comes in spurs, and only sometimes from realizing, despite the many reasons to conclude the contrary, that Black existence and survival is but an improbable, yet divine and thriving, reality. And that, in fact, talking about Black lives mattering in these times means invoking an ancestral capacity to triumph over unfathomable suffering, a centuries-old legacy that fills our veins with the very substance of exuberant, tenacious survival.

***

This past summer, following the lynchings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Elijah McClain, and Ahmaud Arbery among others at the hands of the U.S. police, a renewed urgency propelled me to reconsider my position within the movement and my duty to fight for justice. In the spirit of reclaiming the archive, the writings of Black authors, particularly those in the Black radical tradition, were my starting point. I felt inspired and energized. I was determined to march along the path of justice alongside the thousands of others who took to the streets and to grassroots organizing and to committing themselves to radical pedagogies of liberation. However, I was at a crossroads—I attended protests but found myself adrift in a sea of reactionary emotions, unsure of how to settle years of accumulated rage on firm ground. Sharing this amorphous rage/grief with hundreds of Black people was nurturing, uplifting, and healing. But it also illuminated for me the need to bring my spiritual self to the center, even as I move forward in the struggle.

While the BLM movement was at its most active, then, I found myself instinctively drawn to the insights of those who regarded spirituality and social justice not as separate spheres of thought and engagement, but for the intimately bound endeavors that they are. As a result, I deliberately filled my reading lists with works of Black Muslim thinkers and revolutionaries on both sides of the Atlantic. What I found had a profound impact on how I conceive the intellectual genealogies of Black radical thought.

There are certainly excellent and very much alive branches of Christianity, specifically Black Radical Theology that offer invaluable lessons and deserve our attention as possible loci of structural change. My focus is on Islam in part due to personal reasons, but it also bears recognizing that, in a post-9/11 world, Black Muslimness inhabits a discursive social location where a multitude of phobic, fear-filled, and targeting axes collide.

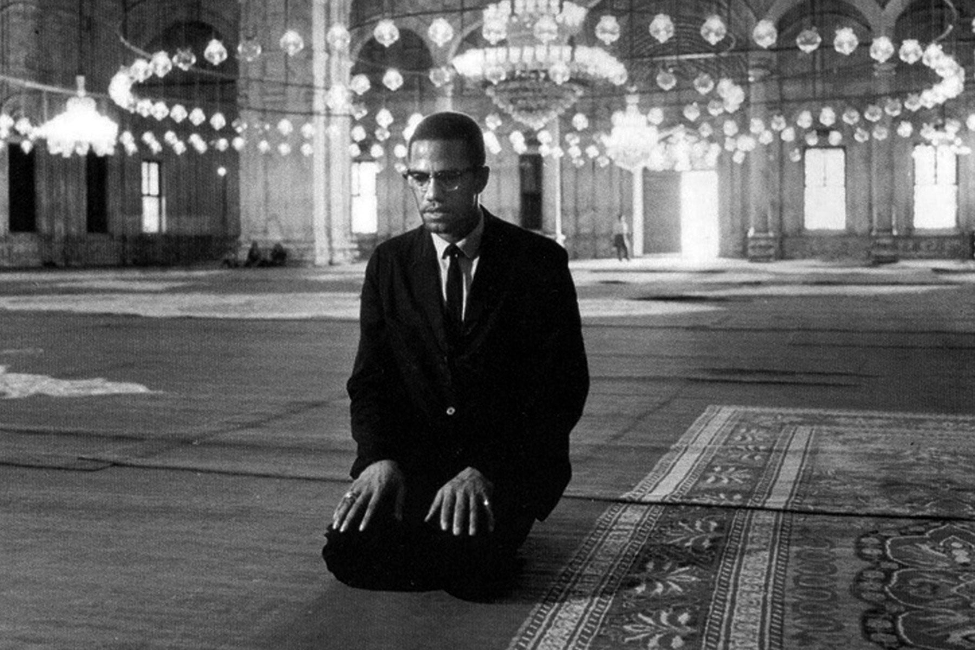

But more importantly, locating Black radicalism as a nonaligned, transatlantic genealogy that is rooted in Islamic principles allows us to expand the horizons of our intellectual and spiritual heritage in unexplored and generative ways. In this context, my aspirations in facing the archive involve an attempt to understand el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz, aka, Malcolm X, as both a militant Black radical and a spiritual leader who understood, specially later in his shortened life, that true equality in the post-1492 world can only emerge from a paradigm shift that begins in the self, at the core of each soul who fights in the struggle. In this light, Malcolm X cannot easily be contained within the canon of Black radicalism (among the likes of W.E.B. DuBois, Audre Lorde, Frantz Fanon and others). Dr. Zain Abdullah, scholar of religion and society and Islamic studies at Temple University, takes a more generous approach to Malcolm X’s legacy by locating him simultaneously in the Black religious tradition of Denmark Vesey, Nat Turner, Sojourner Truth, and Harriet Tubman for whom religion, politics, and justice were intimately and irreducibly entangled with the question of Black liberation[1].

Some have argued that the opposite was true about Malcolm X. According to Edward E. Curtis IV, who has written extensively about religion in the African diaspora, the Minister was in fact never successful in articulating a “pan-Islamic strategy for black liberation,” which is to say, he was never able to spouse his political and spiritual beliefs under the same framework for social justice[2]. Indeed—through and despite his religious path, Malcolm X’s politics remained committed to a Black internationalism that found theoretical support in pan-Africanism and Human Rights discourse, and it was these (as opposed to legal or political Islamic sources) that infused Malcolm X’s mind with the exceptionally illuminated political consciousness for which we know him today.

But this is not, as Curtis defends, due to the irreconcilable nature of the ostensible universal uses of Islam (what may have led Malcolm X to a coherent discourse of pan-Islamism, but failed to do so, according to Curtis) and the particular needs of Black Americans. Much on the contrary, the lessons we draw from Malcolm X’s life of ceaseless reinvention is that when faith becomes part and parcel of a person’s life struggle, when religion is regarded not as legislation but as ethical guidance and as an embodied way of life, the putative separation between the universal and the particular collapses in the lived example of a person from whom religion was inseparable from flesh, just as universal justice was (and is) inseparable from racial equality. Throughout the years, despite or alongside the tumults of his path in the Nation of Islam, the Minister allowed his ever-expanding knowledge of Islamic ethics to command, guide, and inform his actions in the political sphere in such subtle and intimate ways that, as was true for Nat Turner and Harriet Tubman, their influence became virtually indistinguishable from his commitment to political and social action. It is this interpretation on Malcolm’s religious path that leads Abdullah to conclude that “Malcolm rebuked in no uncertain terms any religion that was either unwilling to or incapable of addressing the desperate plight and poor conditions of Black people in America.”[3]

***

But how exactly did Malcolm X grow to embody his faith in such a way? Though the sources are many, tackling the wealth of writings around the figure of Malcolm X is no easy task. Among the most exhaustive and acclaimed attempts at documenting his life is Manning Marable’s ‘Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, and more recently, Michael Sawyer’s attempt–the first of its kind–at producing a coherent discourse on Malcolm X’s political philosophy. In an article written for Black Perspectives, historian Alaina Morgan argues that Malcom’s legacy is as complex and misunderstood as Malcolm the person was. Owing to the Minister’s “constantly evolving” nature which made him illegible to a rigid cultural imaginary, when we approach him from our current perspectives,” says Morgan, “[w]e create and re-create his image according to our contemporary realities in ways that are useful to us.” [4]These complications notwithstanding, it remains indisputably true that Malcolm wanted us to remember him by his autobiographical testimony, and it is in that text that we get a picture of his spirituality and path within Islam, a path that transfigured his inner and outer life many times over, from Detroit Red, to Satan, to Malcolm X, to El-hajj Malik El-Shabazz.

***

Malcolm’s testimony in his Autobiography evidences that the teachings of Islam were a central pillar in his life from the day he first encountered the religion as an inmate in Charlestown State Prison, about which he says: “I had sunk to the very bottom of the American white man’s society when—soon now, in prison—I found Allah and the religion of Islam and it completely transformed my life” [5].

One of the tenets by which Malcolm X stood firmly throughout his life was that of legitimate use of violence, or self-defense, which he saw as a necessary component of the civil rights struggle. On more than one occasion, the Minister publicly decried both the non-violent approach of Reverent Martin Luther King Jr., and the religion that had taught Dr. King and so many Black Americans to turn the other cheek on white supremacy’s aggressions, and “suffer peacefully.” “That’s [Uncle] Tom,” he said in his speech, Message to the Grassroots, on December 1963, “keeping you nonviolent […] keep[ing] you and me in check […], under control, […] passive and peaceful and nonviolent”[6]. In contrast to what he considered to be fundamentally limiting in Christianity’s teachings, Islam’s vision of justice sanctioned the use of principled militant action to defend those oppressed in a society. Malcolm X attested to this principle in the same speech: “There’s nothing in our book, the Quran […] that teaches us to suffer peacefully. Our religion teaches us to be intelligent. Be peaceful, be courteous, obey the law, respect everyone; but if someone puts his hand on you, send him to the cemetery. That’s a good religion.” Less than a year later, at an Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), he pronounced that “any time I have to accept a religion that won’t let me fight a battle for my people,” he surmised, “I say to hell with that religion”[7]

But what continues to fascinate me as I read and re-read the Autobiography, and what continues to be dismissed in the major works that address his life, is the dimension of Malcolm X’s religion that speaks directly to the self–the kind of rigorous, honest inner work that transformed Detroit Red into the international spokesperson he was up until his final breath in the Auburn Room. There is no doubt that Malcolm X was attracted to the embodied ethics that Muslims are encouraged to practice, and this principle–moral rectitude–, too, was indispensable in the civil rights struggle according to his vision.

In addition to a complete renegotiation of terms in the relationship between Blacks and the American state, Malcolm X believed that solving the race problem would require a reform in the way the Black community regarded itself, how each soul related to itself. Despite the polemicized form of Islam that encountered Detroit Red during his incarceration, what remains beyond doubt is that there was something in this religion that provided young Malcolm with a map and a compass to orient his personal own growth in the direction of self-respect. As Frantz Fanon articulated in BSWM, to respect oneself as a young Black man was so inconceivable an idea within the world paradigm of colonialism, that it would take something comparably vast and all-encompassing to dismantle the psychic structures that contained it. The Minister would articulate, years later, that this paradigmatic shift, beginning inside one’s mind and soul and of which moral rectitude was just a ramification, was to be the bedrock of a spiritual awakening without which it would be impossible to “rise above the evils and the vices of an immoral society”[8].

Conceived as such, little remains of the idea that spirituality and politics were separate domains of being and action for Malcolm X. The legacy of this civil rights leader is an example to us precisely because he allowed his spiritual growth to lead the path his public persona would then follow.

Toward the end of his life, in his first and last trip to Africa and Arabia, Malcolm experienced what he called “love, humility, and true brotherhood” among the multiracial group of men and women whom he met during Hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca that is made obligatory to all Muslims who can afford it. By having experienced relationships with Whites outside of the prejudices of racism, the now Hajj Muslim concluded that if he—he whose entire life had been spent at the shadow of America’s brutal anti-Blackness—could live to see a mutual recognition of Blacks’ and Whites’ nature as divine, rather than biological, beings, then everyone, including white Americans, could do the same. In his autobiography he puts it this way: “perhaps if white Americans could accept the Oneness of God, then perhaps, too, they could accept in reality the Oneness of Man— and cease to measure, and hinder, and harm others in terms of their ‘differences’ in color”[9].

The pilgrimage, or the Hajj, was for Malcolm precisely what Hajj is intended to be—a struggle that challenges the undertaker in the most physical, fleshy ways, urging them to trace whatever distance separates her home from the Qibla, at the heart of the Arabian Peninsula, only to lead her back to her true home, the immaterial refuge of her inner self. When Malcolm completed Hajj, the inner journey of that trip had immediate outward implications for how he would approach his plight for the liberation of Black people, completing the cycle from physical pilgrimage, to inner transformation, back to the world as an agent of emancipatory justice. It was from then forward that the minister would begin to contextualize the African American liberation struggle within an anti-imperialist, Pan-Africanist framework, and it was also at this turn that he understood America’s racial prejudices to be a human issue whose eroding effects were universally harmful.

At this moment in the history of humankind, where the soullessness of racial capitalistic violence emerges as a multifaceted thread encompassing police brutality, global warming, and fascist politics—we must regain a spiritually-centered approach to engaging socially in the struggle for human liberation. As we seek for precedents whose spiritual roots manifested politically, what Malcolm X’s radical politics have to offer is a uniquely valiant model of a man whose political leadership emerged from, but ultimately transcended, his religious beliefs. As I contemplate the current social and political scene, while vehemently yearning to become part of the forces that will lead us toward justice, I too strive to embody the principled, spiritually and socially speaking, way of life that Malcolm X strove for in his endeavors.

As a thought leader, as a defiant voice who spoke the words nobody else dared to speak, and as a man who willingly gave his life to what he believed was Allah’s chosen path for him—the liberation of his community and of mankind—Malcolm X the militant, and Malcolm X, the thought and spiritual leader, continues to mobilize Black people’s need for alternate ways to confront a seemingly unsurmountable wall of injustice. From every corner of the earth, from Muslims and non-Muslims alike, his legacy lives on both as manifested inspiration and as potential. It is up to our current leaders and those of us involved in the movement to reach the kernel of his life as a lesson, interpret it in our own terms, and strive, as he did, to embody first and foremost the principles we yearn to see actualized in our imagined, reconstructed worlds. This, I believe, is what Malcolm X strove to do—that is Malcolm X as a method.

_____________________

[1] (205). Abdullah, Zain. “Malcolm X, Islam, and the Black Self.” Malcolm X’s Michigan Worldview: An Exemplar for Contemporary Black Studies, edited by Rita Kiki Edozie and Curtis Stokes, Michigan State University Press, East Lansing, 2015, pp. 205–226. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.14321/j.ctt13x0p7v.16. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

[2] (96) Curtis, Edward E. “Why Malcolm X Never Developed an Islamic Approach to Civil Rights.” Religion, vol. 32, no. 3, Routledge, July 2002, pp. 227–42. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, doi:10.1006/reli.2002.0400.

[3] Abdullah, 215.

[4] https://www.aaihs.org/writing-and-re-writing-the-legacy-of-malcolm-x/

[5] (97) X, Malcolm. The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Edited by Alex Haley, Ballantine Books, 1992.

[6] https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/1963-malcolm-x-message-grassroots/

[7] http://malcolmxfiles.blogspot.com/2013/07/oaau-homecoming-rally-november-29-1964.html

[8] (9) X, M., & Breitman, G. By any means necessary; speeches, interviews, and a letter. New

York: Pathfinder Press. 1970.

[9] Autobiography, 198.

I really really love this piece.